Akshay Anantapadmanabhan

50 uniformed children, ages 5-10, happily clap their hands and recite konakkol phrases to a refrain of simple instrumental music from a cell phone. Just some twenty minutes earlier, their master of ceremonies had gently introduced the word ‘rhythm’ and got the children to chip in, conveying the message that rhythm was everywhere. “Water dripping from a tap”, said one child. “The sound of insects.” said another. At the end of the 45-minute session, the children’s eyes were bright with fascination, having learned about the mridangam, kanjira, konakkol (“all three words have three syllables”) and the cajon, (a Latin American percussion instrument).

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu.

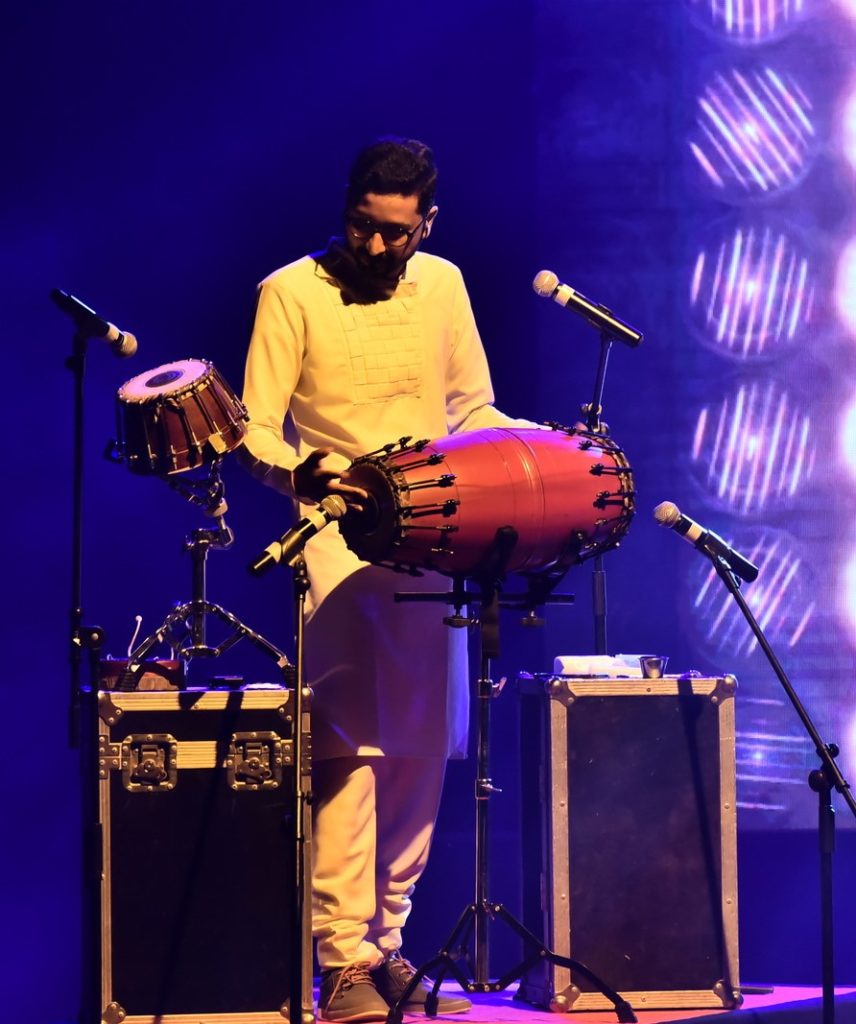

Akshay Anantapadmanabhan exudes a calm and collectedness well beyond his years, characteristics that put those around him at ease instantaneously. He is soft spoken and very articulate, possessing the ability to deconstruct complex thoughts into understandable nuggets, keeping in mind the demographics of his audience – this workshop for school children (as part of his association with SaPa – Subramaniam Academy of Performing Arts) being but one example. Adding to the overall likeability factor is his sartorial sense which, like him, is striking in its politeness – neither loud nor staid – but clearly there.

Probably the most recognized figure of Raga Labs and IndianRaga (famous for their well-produced classical-arts-based videos), where he was one of the initial featured artistes and, now, a mentor, Akshay spent his primary school years in India, followed by over one and a half decades in the US. “IndianRaga reached out to me in their very first year – 2013 – they were looking for established artistes in the US.” he says. He spent many years traveling between both countries. While in India, he worked with IIT Madras on their CompMusic project.

In the Carnatic scene, Akshay has accompanied numerous artistes including Sangita Kalanidhi RK Srikantan, Sangita Kalanidhi Sudha Ragunathan, OS Thiagarajan, Sangita Kalanidhi N Ravikiran, Lalgudi GJR Krishnan and Lalgudi Vijayalakshmi, P Unnikrishnan, TM Krishna, S Shashank, Ranjani and Gayatri, Sikkil Gurucharan, Ramakrishnan Murthy, Sandeep Narayan, Vignesh Ishwar, Sriranjani Santhanagopalan and more.

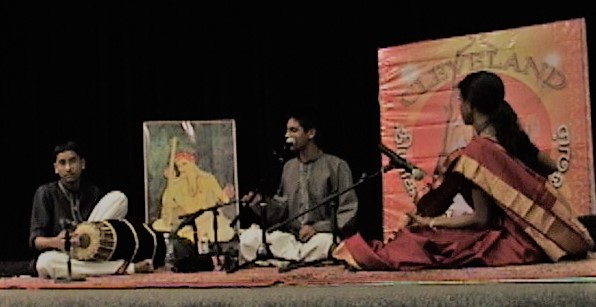

Vocalist Ramakrishnan Murthy has known Akshay professionally since 2005 when they first performed together, as teenagers, in a highly acclaimed concert at the Cleveland Thyagaraja Aradhana. He says “Akshay is the quintessential millennial mridangist who effortlessly straddles genres from pure, classical, Carnatic music to contemporary Indo-Western fusion – to maintain the purity of the classical artform AND to be open to ideas and execute the requirements of a fusion musical ensemble requires a very open mind and versatility in one’s expertise. I have been amazed by these qualities in Akshay.”

Akshay likes to explore music in a multitude of ways and in different contexts. “When you create music outside your comfort zone, you may actually discover something new,” he says. “Engaging in different outlets gave me a lot of exposure on what is involved in making music in the 21st century space – recording, getting into a studio and finding your sound, for instance.” In the independent music scene, Akshay has been most recently involved with The Thayir Sadam Project, Carnatic 2.0 Reloaded and his own latest solo performances highlighting the possibilities of Indian rhythm outside its traditional context. He has published several academic papers related to Indian rhythm with New York University, Abu Dhabi, and IIT Madras.

Akshay first came to India on a year’s sabbatical – before intending to join the PhD program in Music Technology at the University of California at Santa Barbara. He ended up staying permanently. His US association initially resulted in local artistes assuming that he was based abroad and thus, not being thought of as an option locally. When he made the decision to be based in India though, things started falling into place. He also did not face some of the (now rather common) pitfalls of NRI-dom, including, but not limited to, having to pay hefty sums to get a local concert opportunity – he feels he arrived rather earlier on before the true influx began.

Akshay is very much involved both in the independent music and in the mainstream Carnatic kutcheri arenas, and he explains that, contrary to popular belief, each has benefited the other. For example, he says that the recording studio environment makes one really pay attention to the tuning and the tone of the instrument. “In the studio, when one is listening on the headphones to only one’s instrument and the tambura, it can be disconcerting. It is extremely difficult to just align the instrument to the sruti perfectly. It is critical, though, in this environment to make sure that what I play is exactly to point AND tuned to perfection.”

This experience has made Akshay much more cognisant of the tuning in a kutcheri setting too. Sudha Ragunathan affirms, “Akshay is very conscious of how he presents himself and his instrument – the quality, timbre and resonance.” Akshay elaborates, “The mridangam is not a synthetic drum. Regardless of how much we might tune it, when we go to stage, it will require retuning. If I am unsure of how that particular instrument will behave, I will spend a good 1.5 to 2 hours playing it before a concert. The mridangam really is like a person. The more time you spend with it, the more you will be aware of its mood swings.”

He enjoys moving between genres, from the one mind space to the other. Different skill sets are involved for each. In the studio setting, most productions go through multiple iterations, with every artiste aware of exactly what they are going to play and precisely when and where to play it. In some, each records his/her part to perfection, individually, to be mixed later with the artistes sitting together for the visuals, effectively acting out their roles. Akshay says that to remember what one played and to repeat it perfectly is a very difficult task – and that he has worked on coming up with what he knows he can subsequently remember.

In a traditional kutcheri, the lead melody artiste will often not share anything of what he/she is going to do. “If I am confronted with something I don’t know, a Pallavi, for example, I take a few rounds to figure things out. That response is the making of music and the learning process. Each concert and each experience is learning. We are always creating content, constantly composing, so to speak. The selection of content and the desire to keep pushing oneself has come from the kutcheri experience. It forces us to engage in that mental exercise and keep thinking outside the box. This has definitely helped in the recording scene too.” According to Sudha Ragunathan, “Akshay is very attentive. Even if he is not familiar with a composition, he quickly latches on to the rhythm and innate emotion of that piece.”

Akshay says rightly that while Carnatic artistes have spent a lot of time in understanding how their instruments sound by themselves, few are aware of how it sounds (or should sound) through a microphone, and how to make it sound authentic through the amplification. This is not something the sound engineer would know (the fact is, as Akshay says, it is often a sound electrician on duty in traditional kutcheri platforms). Akshay selects his instruments and asks for the sound to be a set in particular ways based on his knowledge of the specific intricacies in the different spaces (when he attends others’ concerts, he notes the sound from the audience perspective as well as how each technician handles the sound at that venue). This awareness and planning ahead of time means that Akshay requires little time for sound adjustment once he does ascend the stage.

Akshay believes in being sensitive to the overall sound and not just his own left and right balance. “It is important that the entire stage is balanced and that we be aware of the overall sound.” Sudha Ragunathan appreciates Akshay’s quick discernment of the varying sound conditions in each venue and his making the appropriate adjustments with the sound technician. She explains that he sets an ambient balance in his instrument while ensuring that the vocal is clearly heard above the mridangam – so that the mridangam actually compliments the music.

Asked about the touchy topic of some mridangists being overwhelmingly loud, Akshay explains that excessive volume is not limited to percussion and that Carnatic music, as a whole, tends to be rather loud in the spectrum of sound – something for the fraternity to think about. That he has analysed it is clear. “While both the sound on stage and the sound outside are handled by the sound technician, the performers get the sound on stage adjusted to their comfort level. The sound outside is entirely in the hands of the technician. Another aspect is when we, the performers, ask for sound to be raised on stage, it can be raised for the audience, which is perturbing for both us and the listeners. This is another reason I don’t fidget too much with volume once on stage. One can quickly decipher the sound engineer’s ability to handle sound during the sound check itself.” The fix for this is simple, of course. One hopes sound technicians will elicit the help of another competent individual to check the sound and balance from the audience’s perspective.

In video productions, Akshay comes off as at ease and a total natural before the camera. He says he has learned over time, adjusting not just the external countenance and posture, but the content presented too. “The recording space has an instant feedback loop – there is a rigour and practice there – you learn from listening to and watching yourself. Even a 5 minute segment for just the mridangam could take hours to record, and after multiple takes, sometimes, I might not like how I sound and decide to do things differently.”

A certain amount of open-mindedness, guts and a lot of faith in oneself is required to embark on independent music projects. The Thayir Sadam Project band, for example, (whose other members are Bindu Subramaniam, Ambi Subramaniam and Mahesh Raghvan), was an organic creation upon realising they were producing an interesting sound. Two of their biggest productions included Crazy Little Thing Called Chakravakam (in collaboration with vocalists Ranjani & Gayatri) and Loka Samasta (in collaboration with vocalist Sangita Kalanidhi Aruna Sairam), with the former reaching over one million views on Facebook.

Akshay started on mridangam at the age of 5 in Bombay, at Shanmukhananda Sangeetha Sabha with TS Nandakumar, his parents observing his general tendency to tap on any object around. His aunt used to sing, and Akshay’s sister too learned vocal. At this stage, Akshay merely learned routinely. It was not until he moved to the US (where he learned under Venkat Natarajan, a student of TH Subash Chandran), that the passion really set in, kick-started by the preparation to accompany his sister’s vocal program (in 2001 when he was 12) – his first performance. “That introduced me to the space of a kutcheri, but it was not my arangetram. My arangetram (2002) was a turning point in terms of the opportunities I got – I started getting calls from serious artistes. I played everything under the sun. My parents drove me literally everywhere within driving distance.” Akshay played at the Cleveland Aradhana competitions in 2004 and 2005 (where he won the first prizes) where his judges included Sangita Kalanidhi N Ramani, Sangita Kalanidhi Vellore Ramabhadran, Guruvayur Dorai, Srimushnam Raja Rao and more. “Though I was familiar with the names then, their stature as artistes did not sink in until much later,” says Akshay.

Soon, Akshay started learning directly from TH Subash Chandran himself. “Music was intertwined in an overall fun atmosphere that helped sustain the interest, I think.” That interest was further piqued when he played concerts that challenged him. He mentions his accompanying RK Srikantan – “probably the artiste with the most age difference – I think I was 19 and he was about 90,” he says. “Senior artistes would be teaching me even as they sang, taking me along with them – it was particularly noticeable with Srikantan mama.”

Akshay was a serious tennis player and on his school and college’s teams. It was thus a juggle between sports, academics and music and he recollects ramping up the mridangam practice before his arangetram. “I would come back after school and tennis at about 6, finish homework and other things by about 10 and from then on practice mridangam until some 1 or 2 am. Very often, I would fall sleep on the mridangam and my mom had to wake me up and send me to bed. I would then continue sleeping in my first class the following day – usually History,” he says, describing his middle school days. That rigour continued for many years after that. “I became less aware of how much time passed during practice by then.”

Akshay did his degrees from Cooper Union (graduating with a flawless 4.0/4.0 GPA in his Master’s degree), a selective private college in New York City, which allowed him to continue his nexus with music uninterrupted. Weekends involved music. “I would lug my mridangam everywhere – clubs, pubs, the metro. I got exposed to the jazz scene and other kinds of music too.” He currently collaborates with New York University’s Abu Dhabi campus on Intelligent Generative Rhythmic Systems, where fed with some basic input data, the computer will generate Carnatic type rhythms. The eventual goal is to make it a compositional tool for the western music space.

On his noteworthy tranquil demeanour and professionalism, Akshay says, “I like to prepare to be calm – to plan for what might happen and account for it. The more situations I prepare for, the better I am able to deal with it. Professionalism? It IS my profession. My having worked for a year was probably helpful too. I like to treat others the way I like to be treated. Music itself is very calming for me. Even as I see water enter the ravai, it resets my mind into the stage mode. I am generally calm outside the stage too. Unless it is a dire situation, there are fixes to most things. My Engineering education has helped me look for solutions rather than focus on problems. I can think about certain things and calm myself down. In the concert setting as well, if something is not going as it should, I consciously try and stay calm, regardless of any thoughts I might have in the back of my mind.”

If about to play for a new artiste, Akshay will always check out at least one program of that individual’s online and, ideally, also attend a live concert to get an understanding of that artiste. He also advocates listening to artistes that one plays for particularly if there has been a break for any reason. “Both of us, hopefully, would have evolved in that time – it is like a friendship and requires some maintenance.” Akshay too, like many percussionists, enjoys playing for the melody more than the tani Avartanam.

Akshay generally keeps his tani Avartanam-s short – to usually no more than 10-15 minutes in a 2.5 hour concert – this is noticeable – even as many mridangists go 50% longer if not more. The average rasika is often unable to take extended tani-s, perhaps craving from some melodic relief. Sudha Ragunathan commends that innate sense of proportion and Akshay’s not going overboard with the duration of the tani. “I like the notion of keeping things compact and, in that compact form, achieving as much as possible – striving towards choosing the phrases carefully. The tani Avartanam, for me, ideally, should be a reflection of what has already happened – taking an idea generated earlier and incorporating it in a way that seems appropriate. I try to maintain the mood of that song, building up to the farhans and mohra to bring the climactic effect with the final korvai having a sense of coming back to the song and the mood – so it is not a random cut and paste between the melody and the tani. One segment of the tani I always try to include is sarva lagu (the kind of rhythms that have a generally groovy feel to it – that you would tap your feet or bob your head to) – what I believe is the most relatable aspect for rasika-s and musicians. If it is a very short tani, I might just do sarva lagu and move to farhans, mohra and korvai.”

Like any accompanying instrumentalist, the mridangist can be confronted with a less preponderant tALam at any time. Akshay finds that he plays very differently in such situations, unearthing something new – he thus regards these opportunities as discovery and learning. When the melody is going on, a percussionist can use that as a guide to play appropriately. From the practical standpoint of the actual decoding of the less familiar rhythmic cycle in the tani, Akshay shares how he might deconstruct it: “For a tAlam that has lagu (finger count) and drutam (clap and flip), I would think of those as two sections and play each accordingly. Kanda jAti tripuTa tALam, for example – the first half is a type of naDai. One can reduce the spaces between each until they start converging. This is one strategy which will give more scope for exploration – you could do four 5s four 4s once, two 5s two 4s twice, one 5 one 4 four times. You can then work backwards, fill in some 4s with a sollu. What I am more interested in, though, is how to build the story. Right off the bat, I observe the lagu drutam count, and calculate the total count of the tALam. Then I can figure out what korvai I want to play. That korvai, however, should not be irrelevant to everything else I have been playing. That is where the music comes in. What is the journey from Thought A to Korvai X and in that journey, how well am I incorporating the thoughts that were already sung?”

About the tendency of mridangists to jump in the fray in the last, longest sequence of kalpanaswara-s if and when played by the accompanying violinist (in concerts with multiple percussionists), Akshay explains that it is usually a point when the music is reaching a crescendo – one where multiple layers of sound can give the appropriate gravitas. “The mridangam and mohrsing, in particular, have so much nAdam around the upper shadjam and it sounds nice to have them there.” On how he adapts his playing for varying voice timbres, ceteris paribus, Akshay explains that he alters the force he applies on his instrument accordingly.

Violinist Lalgudi GJR Krishnan says, “Akshay is a passionate artiste with an enthusiasm to keep learning. He is a pleasure to be with, has an open mind and the ability to adapt. He has the right temperament and his playing is focused and unobtrusive.”

Getting prepared for a kutcheri or any other program has both mental and practical sides to it. Akshay stresses that, as with his viewpoints on many aspects, these too constantly evolve. “With shows, I think about it well before the program, deconstructing everything I should do even before I get there. Kutcheri preparation is quite systematic – I first select the instrument, set the sruti, then practice some sarva lagu, farhans and mohra in different speeds – this helps with the overall warm-up. Then, if possible, I will practice a nadai.” Another aspect of prep for him is active listening. “If I feel I did not do full justice to some piece earlier, I will listen to renditions of that song or that type of piece, for example.” Akshay has 15 mridangams, with multiple ones in D and G, the most common male and female sruti-s, respectively.

Besides the mainstay of Carnatic music (“it can never be background music for me– my mind is always fully into it”), he watches the independent music space – the types of sound and genres they are moving towards. He also listens to pop music and enjoys Adele and Imogen Heap a lot.

Akshay plays tennis and table-tennis recreationally. He used to play basketball as well but does not indulge in it anymore due to wrist strain that could affect his playing of the mridangam. He practices yoga which assists in both mental and physical fitness.

Always well groomed and elegantly attired, Akshay believes that there is a definite visual element in all programs too. “’Dress to impress’ is something I believe in. We should show that we care – and I do make an effort for that.” He gives credit to his wife, dancer Sudharma Vaithiyanathan, for selecting fabrics and combinations. Many of his kurta-s are custom tailored for a perfect fit and he often selects a complimentary mridangam cover.

“I strive for my own identity as a mridangam artiste. In the olden days, people came to listen to specific artistes or combinations. I would like to establish myself similarly in the present 21st century scenario,” concludes Akshay.

Many thanks to Sri. Akshay Anantapadmanabhan for sharing his thoughts and locating the photos and videos on this page.

Enjoyed going through this long detailed interview of Akshay. He is still very young and I am sure that he will achieve a lot more in his professional career . He is a very passionate individual and is clear on what he wants to achieve.

I wish him all the best in all his endeavors and a great future in standing out as a unique personality in his Profession.