Anirudh Athreya

Anirudh Athreya, kanjira exponent, elicits copious appreciative comment from fellow artistes. Senior mridangam vidwan K. Arunprakash says, “He is a genuine team player, knowing how to enhance each of the other artistes on stage.” Vocalist and violinist Amritha Murali notes, “His sense of aesthetics, care and sensitivity towards his own music and that of his co-artistes and his commitment towards the musical experience of the day, is most commendable.”

Cheerful, warm and involved, Anirudh is an integral part of concerts galore and is featured with practically all known artistes. One is often surprised at how perfectly his playing fits the rest of the music, particularly the unscripted, manodharma aspects. He diligently pays attention to all his co-artistes, observing the mridangist’s hands carefully, for example, to anticipate what might be played, and maintaining eye contact with the violinist for whom, as upapakkavadyam, he would play for frequently.

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu. Many thanks to Sri. Anirudh Athreya for sharing exclusive photos and recordings for this page.

Anirudh grew up in a large joint family that included grandfather V. Thyagarajan, violinist and Thyagarajan’s younger brother, V. Nagarajan, kanjira vidwan. Anirudh’s maternal great grandfathers were Sangeetha Kalanidhi Papa Venkatramaiah, violinist and Sangeetha Kalanidhi Alathur Sivasubramania Iyer, one half of the Alathur Brothers (who weren’t brothers).

Anirudh would peep in on older cousin KS Ramana’s mridangam lessons with Nagarajan. After momentary trysts learning vocal and violin from Neyveli Santhanagopalan and his grandfather, Thyagarajan, respectively, Anirudh knew that he preferred percussion. Unlike many who begin percussion lessons on the mridangam, Nagarajan began Anirudh’s training directly on the kanjira, in 1997, when Anirudh was 9.

He recalls injuring his wrist at tennis. Receiving a tongue lashing from Nagarajan (“Is he going to become Pete Sampras?”), his parents immediately withdrew him. “From then on, there was no playtime. It was always practice,” Anirudh recalls. He HAD to practice kanjira every morning for about an hour and, again, right after school. With the Guru in the house, there was no escape. 4-6 hours a day was routine. “Thatha would be sitting on the porch. I would even try ducking to avoid him.” In 2002, Nagarajan had introduced him to TK Murthy, also of the Thanjavur Vaidyanatha Iyer school, requesting Murthy to guide Anirudh to play for music. That year, Nagarajan died.

Teaching styles were different. Nagarajan would break everything down into readily digestible components and all Anirudh had to do was to play what he heard. Murthy would expect the students to decipher what he played. “Initially, it was very difficult. I would take copious notes, come home, practice and understand.” Anirudh feels that both Nagarajan’s and Murthy’s methods were appropriate for each stage. Had much decoding been necessary, it could have been too much for a young child who needed to first understand the mechanics of producing the sound on the instrument.

including solo from 1.23 to 2.47.

Wood of the jackfruit tree is traditionally used for the frame of the kanjira which is usually made in the process of tavil making. Lizard skin is affixed to the frame using cooked rice paste as glue. Traditionally, ¼ anna coins (with a hole in the centre) were used as jingles for the instrument. Nagarajan, however, had preferred German silver which, later, became very difficult to procure. Anirudh currently uses stainless steel jingles. Compared to the mridangam or the ghatam, the kanjira has much less playing surface and it produces only two tones. These inherent limitations of the instrument mean that extensive practice is required to develop the skill necessary for effective accompaniment.

“Not just I, but everyone in our circle, and seniors too, really admire the sound that Anirudh extracts from the kanjira – the body and tone he produces is excellent.”

-Vocalist K. Bharat Sundar

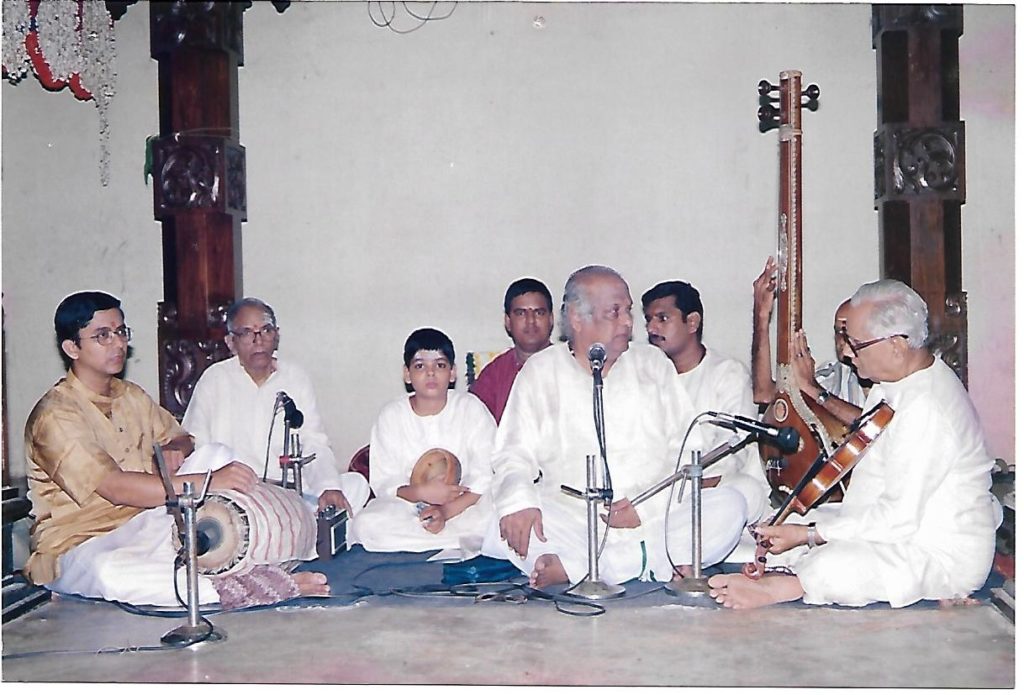

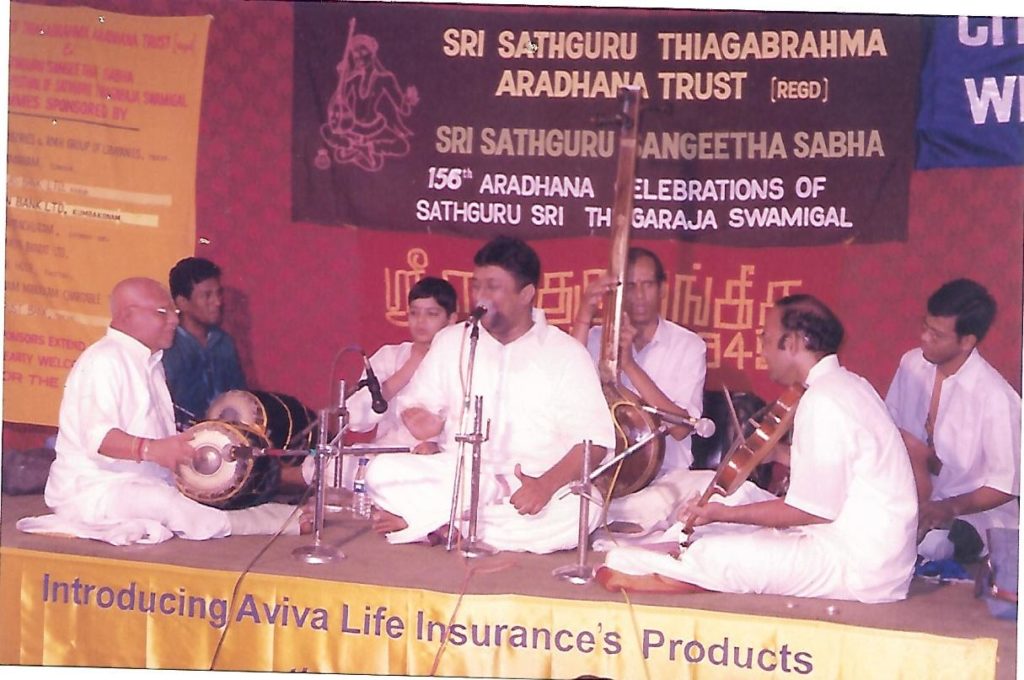

Anirudh’s first performance was in 2001 for PS Narayanaswamy at a wedding concert with both Nagarajan and Thyagarajan and Umayalapuram Mali on mridangam. His first concert with TK Murthy was in 2002 for Vairamangalam Lakshminarayanan. In January 2003, Murthy, who was to play for Sanjay Subrahmanyan at Sathguru Sangeetha Sabha in Trichy, asked Sanjay if 14-year-old Anirudh too could play for him. “Sanjay anna cheerfully agreed.” Anirudh gave his all and thoroughly enjoyed the performance. That concert was a huge success.

Barely two months later, he played with his Guru for RK Srikantan at Musiri House. That concert was attended by Vijay Siva, Sanjay Subrahmanyan, TM Krishna, N. Ravikiran and more. Anirudh had no idea then of the standing of these artistes. Anirudh later received a call from Kartik Fine Arts to play for TM Krishna. “My mother, who managed my concert engagements, was taken aback. She asked again if it was indeed me they wanted.” “Krishna has specifically requested him,” she was told. That was his first major concert in the season – on December 10th, 2003. Nowadays, he has at least one concert each day from the end of November to 2-3 daily during the peak season.

In 2007, Sriram Gangadharan fixed Anirudh for his concert at The Music Academy. Anirudh was later surprised to receive two letters of engagement, for the same day, from the Academy – the second for TV Sankaranarayanan who had specifically asked for him. V. Subramaniam, senior disciple of Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, who attended that concert, told Anirudh that he had played very well and had been reminded of Nagarajan. Anirudh received the Best Kanjira Artiste award in the Senior category for that concert – his maiden year at the Academy. “Sankaranarayanan Sir recommended me for the Yuva Kala Bharathi and the Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar too,” he says reverently. Besides these prestigious recognitions, Anirudh also received the Kalki Krishnamurthy Award and Krishna Gana Sabha’s Yagnaraman Award of Excellence.

Upapakkavadyam artistes rarely have direct line of sight with the artiste at the centre. “I sit such that I have a profile view of that artiste. I generally use the mridangist as my first point of reference, followed by the violinist. Both of them have already done some interpretation of the artiste at the centre.” Anirudh says that following a vocalist is often easier since being able to see the mouth helps with some lip-reading. With the violin, one has to go by the flow of the playing.

When it comes to accompanying artistes that he has not played for before, Anirudh will ask other artistes who have played for them and/or watch videos to get an idea as to how that person sings/plays and how he might accompany him/her. However, he insists that much of the learning is on stage. “I will start cautiously and observe carefully. I will watch for what accents their music the best, what he/she is comfortable and uncomfortable with, and adjust my playing accordingly.”

How one handles unexpected occurrences speaks volumes. When Anirudh was playing for Bharat Sundar some years ago, the kanjira broke during the thani avarthanam, with the jingles flying afar. “Picking up another kanjira, Anirudh restarted exactly where he left off,” Bharat recalls appreciatively. Anirudh routinely carries four kanjiras to every concert.

Arunprakash says, “Anirudh has absorbed the difficult aspect of properly supporting and enhancing by playing what the music demands.” Amritha adds, “Success sits lightly on his shoulders.” Anirudh puts it simply, “The art is more important than the artiste.”

Feel proud tobe a relative of atalented music professional pray god to bless this youngster to reach great heights