K Arun Prakash – The Tunesmith

When Jayalakshmi Balakrishnan suggested to the family of the Late Sundaravalli Ammal that some of the lady’s compositions be set to tune and performed, she also knew exactly whom to entrust the task to. Most know K. Arun Prakash as an erudite and avant-garde mridangist. However, besides percussion, he is a very knowledgeable musician and a passionate and skilled tunesmith and composer too. He says, in fact, that he looks at every composition from the aspect of its tuning and has done so since the age of 6.

This article was written for the book Sundara Amutha Ganam at the request of Smt. Jayalakshmi Balakrishnan of Naada Inbam and the family of the Late Smt. Sundaravalli Ammal, represented by Dr. Amarnath Ananthanarayanan. A special word of thanks to Sri. Sekhar of Naada Inbam and Sri. Nick Haynes.

Arun Prakash was given a compendium of Sundaravalli Ammal’s compositions, all of which are in Tamil. There were some that had already been notated earlier, and others where she had suggested ragam-s. He chose ten pieces that had no specifications. The first thing he did was to read the lyrics one composition at a time, noting what deity/kshetram it was on, registering its meaning and the emotion therein. This crucial first step was the cornerstone for deciding several subsequent aspects including what ragam(s) would be suitable, what speed (kalapramanam) it should be set to, which junctures in the piece should be stressed and, of course, what talam would suit. These might seem basic aspects of tuning, but within each, Arun Prakash went beyond.

For the most part, he chose ‘pracheena’ ragam-s, those he believes have been in the Carnatic realm for long. “I think that these ragas have actually settled into our genes,” he says. “There were some lyrics that set themselves to tune perfectly in the first iteration itself,” he says. “Others took some thinking and revisiting.” When he first tuned the piece ‘Veeranarayana’, he had set it to Behaag. When he reviewed it a little later, he felt it was missing something. He then re-tuned it to the Kambhoji it is currently set in which, he thinks, does better justice to the ‘veera rasa’ (courage/bravery) it portrays. Until he set each to its final form, Arun Prakash was continually making changes and refining all the tunes he came up with.

Arun Prakash believes that a composition should, on the one hand, evoke recognition and familiarity of the ragam it has been set to whilst, on the other, have some unique tuning aspects that bring forth some unexpected colour that sets it apart. This was another aspect he had in mind.

In the transference of the words themselves to the tune, it was critical for Arun Prakash to ensure fidelity to their enunciation and the maintenance of normal spoken intonation. The sanctity of the lyric as authored is crucial, he says, and believes that a tunesmith’s obligation includes NOT using the artistic license excuse to stretch or split words even slightly outside of common parlance. This added another layer of thought, and complexity, in actually setting each word, in fact, each syllable, to tune within its selected ragam. “Even without music, each word has a sound independently.”

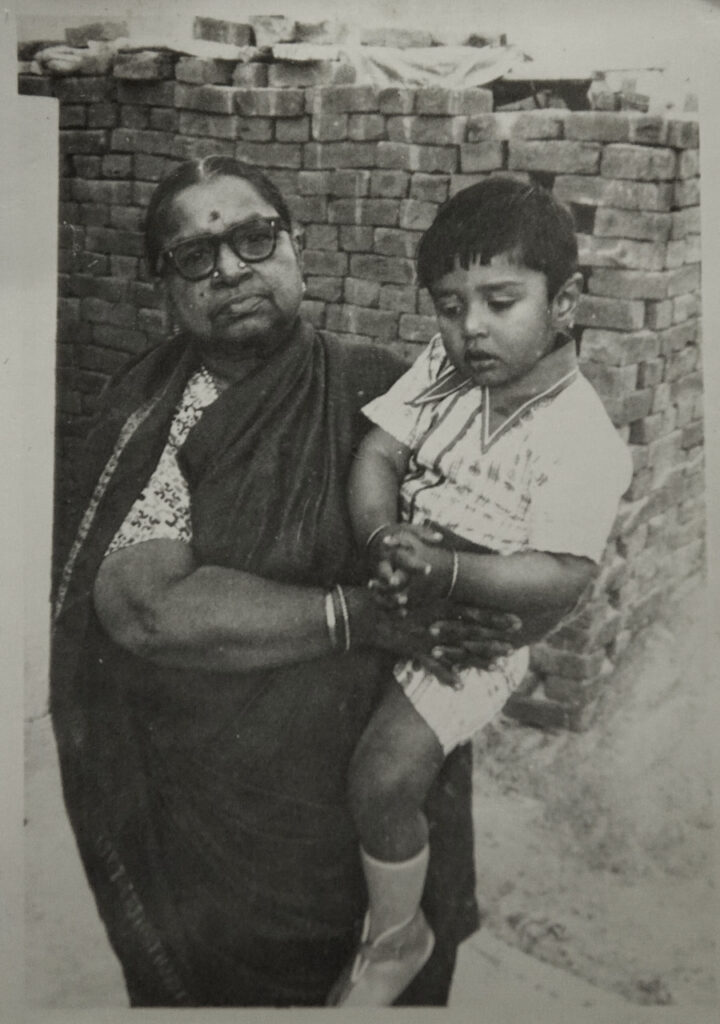

Photo courtesy: Dr. Amarnath Ananthanarayanan via Smt. Jayalakshmi Balakrishnan

He brings out an interesting point referencing Sundaravalli Ammal’s piece ‘ennEramum Sayanam dhAno‘ which means “Is it sleep for you all the time?” referring to God’s seeming procrastination in matters that deserve more immediate attention. This, he says, is a very different feel from the popular Devagandhari song ‘ennEramum undan sannidiyile naan irukka vEnDum aiyaa’ where Gopalakrishna Bharati says he wishes to always be in the Lord’s presence. Even though the first word of both pieces is the same, it was very important, says Arun Prakash, for him to forget the latter well-known and familiar song and convey Sundaravalli Ammal’s different thoughts in the tune that he set. Sure enough, this composition, set to Sahana, crystallises, and reinforces, the sentiment that she seems to be conveying.

He tuned the ten pieces in just about ten days, working whenever he got some spare time. Akin to how sommeliers and chocolatiers give patrons palate cleansers before tasting the next variant, Arun Prakash consciously avoided working on multiple pieces on the same day to avoid the internalised flavour of one corrupting the other even unwittingly.

His expertise in layam is of very significant assistance in tuning, he says, allowing him to unconsciously see the position and placement of syllables within the overall whole. Above all, the rhythmic aspect of the lyric is so internalised in him as to be part and parcel even if he were to merely recite the lyrics sans tune.

Since he was to perform all these compositions and Jayalakshmi had requested an orchestral ensemble, there were further aspects to arrange, coordinate and execute starting from selecting his fellow musicians for the performance.

Arun Prakash expects his orchestral partners to deliver the exact sound he envisions, right down to the smallest nuanced, non-notatable anya swaram. He accordingly selects co-musicians who are able to accommodate his needs more effortlessly than others. Ghatam exponent N. Guruprasad, a long-time partner, understands Arun Prakash’s style and rhythmic structures instinctively on stage and adds to it beautifully. Arun Prakash then invited vocalist Vignesh Ishwar, nadhaswaram exponent Mylai M. Karthikeyan and violinists S. Sayee Rakshith, Madan Mohan and Sandeep Ramachandran, also prior collaborators. For vocalist Aditya Madhavan (great-grandson of Sundaravalli Ammal), flautist Sujith S. Naik and vainika Charulatha Chandrasekar, it was their first time working with Arun Prakash.

Standing (L-R): Sri. Sujith S. Naik (flute), Sri. Sandeep Ramachandran, Sri. S. Sayee Rakshith & Sri. Madan Mohan (violin), Kum. Charulatha Chandrasekar (veena).

Photo courtesy: Sri. Nick Haynes.

As for how he decided on which instruments to use, Arun Prakash explains that since the compositions were all based on temples, the nadhaswaram was a natural fit. He also believes that there is no substitute for that instrument – both in its efficacy and in the auspicious feeling it immediately instils. The veena and the flute are very Indian instruments and integral parts of Indian orchestras. Arun Prakash is a big fan of the strings section of all orchestras and feels that multiple violins produce a thick and rich overall sound – hence the multiple violinists. During rehearsals, the musicians also suggested ideas and sangati-s that Arun Prakash incorporated wherever he thought it gelled with the whole. In one piece, for example, he showcases some harmony, based on Sayee Rakshith’s request.

In Western orchestras, a conductor stands in front of the entire group and waves a baton as needed to indicate who, or which section, is to play at any time. Though the number of musicians there is much more, the fact remains that communication is key to making any ensemble produce a well-coordinated piece of music. Arun Prakash says that for this set of compositions, prior rehearsals have helped each artiste know when and how to begin singing or playing. Further spontaneous communication on stage with the musicians is easily accomplished through eye contact, facilitated by the semi-circular sitting configuration.

Arun Prakash wanted to ensure that when these ten pieces were performed back-to-back, they did not get monotonous for the listeners. “In a traditional kutcheri format, the manodharma aspects provide variety to the ears. Here, that is not the case.” The background music (BGM), thus, plays a critical role. Orchestral performances use BGM at the beginning of songs and as interludes between stanzas They are generally purely instrumental and set listeners up for the upcoming piece and any variations. Arun Prakash composed each BGM, customising it for every piece and the specific lines. “It was based on the ragam-s and in the case of ragamalika-s, the transitions between one and the other as well.”

The BGM aided him in the exploring of both differences and similarities in ragam-s. “That was a personal challenge I wanted to undertake,” he says. In one ragamalika, Kamaas is followed by Nalinakanti, for example, and intentionally, yet he has ensured that the contrasts are clearly brought out in the BGM. Here, Arun Prakash adds that he believes any emotion can be conveyed in any ragam, be it abject pathos in Mohanam or ecstatic joy in Subha Pantuvarali.

His consciously setting the pieces to different talam-s has aided in further concretising variations in structure and gait between pieces. Set in Ekam, Adi, Rupakam, Kanda Chapu and Misra Chapu talam-s, some are in chatusra nadai and others in tisra nadai. Some pieces did not ensconce themselves naturally into a talam, thus requiring him to find creative ways to set it without appearing forced – a non-trivial task by itself and even more so with his other inviolable parameters.

Since he is not only a musician and a tunesmith but also a composer, Arun Prakash is able to appreciate all aspects of music, be it lyric, tune or rhythm, with a higher sensitivity, and comprehends the challenges of getting all these parts to intertwine to perfection. He mentions, for example, several occasions when he and R.K. Shriramkumar, another stellar tunesmith and composer, would exchange smiles on stage acknowledging a shared awareness of the genius of the composer whose piece was being rendered at that moment. Arun Prakash has enjoyed the entire process of setting these compositions of the Late Sundaravalli Ammal to tune, he says, from the actual tuning to the process of arranging them for an orchestral ensemble to seeing, and hearing, the finished product.

About Late Smt. Sundaravalli Ammal.

(As described by her family members in the book – reproduced with permission)

Smt. Sundaravalli Ammal or Sundu paati to my generation was born in 1906 on Purattasi Ketai day to Sri Srinivasan, an advocate, and Smt. Janaki, a homemaker. She was home tutored and keeping with those times, was married at a young age to Sri. K Rajam Iyengar, a maths teacher, and became a home maker. They initially lived in Srivilliputtur which is reflected in the two songs penned by her in this book. Then they moved to Vellore, Srirangam, Nellore, Madurai and Coimbatore as Thatha moved on to a career in life insurance. Not surprisingly there are songs in this book on the deities in Nellore & Srirangam as well !!!

While Sundu paati was not trained is music or literature she would write a song about the deity/temple whenever she visited a temple. We don’t seem to know at what age she started writing the songs but, in this collection, there is a song on Badrinath (which I remember they had gone to from our house in Delhi) so that would have in the 1970s.

Something that I have also seen and corroborated by my cousin, Geeta akka, is that Sundu paati knew all possible songs and shlokas and would recite them during the course of the day. The one I clearly remember is her singing the Raghuveera Gatyam. She was an excellent raconteur and kept both us children and the adults entertained.

But most importantly, both Paati & Thatha were very humble, simple & tolerant people and we have never seen them talk ill about anyone or shout at us for misbehaving. They started living with their children from 1963 and their entire life belongings was infinitesimal just a suitcase each but the love and blessings they passed on to everyone was infinitude. Sundu Paati breathed her last on the sixth day of Navarathri in 1980.

Related Links:

Musicians engage listeners in novel ways

Female composers in Carnatic Music

Charumathi Ramachandran tunes Ambujam Krishna’s compositions

When Vidwan Arunprakash is in command, any project is bound to be a grand success. He has the will and competence to take up any task and complete it successfully.

Each of his co-artists is Numero Uno in their respective chosen field. They would add to the richness of the project.

I wish them all the best.

Thank you for reading and commenting, Sir.