Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar

A comprehensive and detailed interview with dhrupadiya and rudra veena exponent Sri. Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar where he candidly debunks myths, shares personal and family struggles, explains and demonstrates the rigorous, often ‘mystical’ training techniques of the Dagarvani and much more. He also recorded two pieces of music exclusively to accompany this interview, and shared some photographs never seen in public before. Additionally, the interview excerpts allow you to see and hear Baha’ud-din-ji up close and personal.

A brief biography of the artiste:

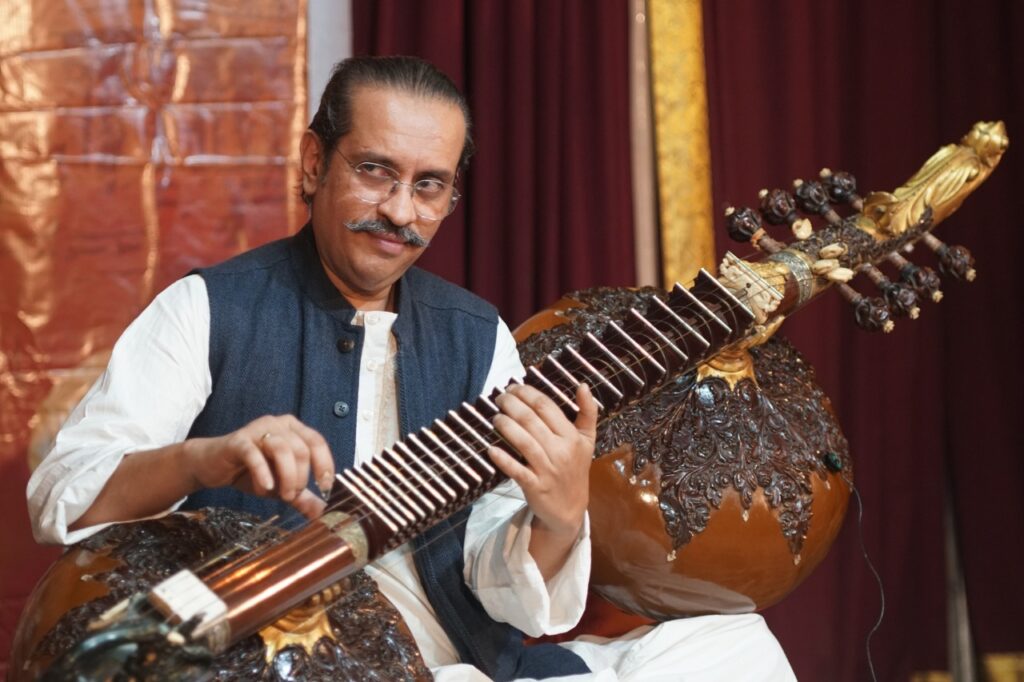

Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar, born in Chembur, Bombay, on 17th July 1970, is a 20th generation scion of the most hallowed family of dhrupad and the foremost exponent of the rudra veena now. He is the son of Zia Mohi’ud-din Dagar, the revered doyen who re-established the rudra veena firmly in its rightful place of recognition. A student of his father and his uncle, Zia Farid’ud-din Dagar, Baha’ud-din-ji’s music reflects a unique depth perhaps stemming from his branch of the family’s unbroken ties to an instrument and vocal. He has focused on faithful reproduction of the vocal syllables in the veena, with precise timing and cutting of phrases in his playing in all aspects of the dhrupad idiom.

He has won several coveted awards including The Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar Award 2012-2013, The Raza Award 2007, The Yuvak Sadhak Award 2007, Bhopal Sanskriti Award 2006, Rashtriya Kumar Gandharva Samman 2014 and the Baiju Bawra Samman 2015. He has performed in august auspices in India and abroad including Tansen Samaroh in Gwalior, Dhrupad Samaroh in Mumbai and Delhi, The Music Academy in Chennai, Sangeet Natak Akademi Fest in Delhi, Darbar Festival in London, Zeitfluss Fest in Austria, Festival du Fes in Morocco and more. He has cut records with leading labels. He is an indefatigable researcher and the inceptor of the ras-veena, where he modified the Saraswati Veena to make the tonal quality more suited to dhrupad. He is currently working on reintroducing the sursringar, another ancient instrument, into dhrupad.

On his training: his early years, how he developed interest in Dhrupad and the challenges along the way.

While you were surrounded by Dhrupad at home, you did not really take it up until much later – you followed a lot of other music initially. Please tell me about your childhood – the family dynamics, the influences – what it was like.

Until I was about 7, my father (Zia Mohi’ud-din Dagar) was based in the USA, teaching at the University of Washington at Seattle. He was saving up for his dream of building a Gurukul near Bombay. My father did not want me to go to the US because he felt that the sanskaar-s (cultural ideologies) were very different in the two countries. So, I lived with my mother (Pramila Dagar) in Chembur in Bombay, going to a convent in the neighbourhood – Our Lady of Perpetual Succour. (Interviewer’s Note: this school’s other alumni include music composer and singer Shankar Mahadevan, writer Devdutt Pattanaik and actor Anil Kapoor.)

My mother would teach sitar at home every evening from Monday to Friday. Whatever she earned through her teaching was what we ran the house on. Whatever my father earned was saved to build the Gurukul. My childhood, thus, was mostly with my mother and her brother, my mama, Chandrashekar Naringrekar (who learned sitar and surbhahar from my father) and my mami, Vimal Naringrekar (who used to learn sitar from my mother). My mother too had learned from my father.

I used to go to my uncle’s house on most afternoons. My uncle was multi-faceted. He had worked at All India Radio, at SNDT College as a teacher, at CBS Gramophone Records, at the Goa Kal Academy etc. He would make me read a lot of books on painters including Leonardo Da Vinci to Van Gogh to Matisse to Degas and other modern artistes too. He would ask me to copy some of those paintings. He himself would sketch frequently. He had a large collection of LP records from all over the world – China, Japan, Russia, Czechoslovakia, Africa, Uzbekistan, Iran, Iraq etc., some of which I would listen to every afternoon, along with All India Radio which my mami would put on. When uncle came home in the evening, he would play jazz. Music permeated the air whether at my home or at my uncle’s. Mama and mami did not have children. I would go with them to concerts. Then, there were programs at various embassies. I got exposed to a LOT of different music that way.

On another level, my mami was very religious and observed all puja-s with great alacrity. (Interviewer’s Note: Baha’ud-din-ji’s maternal family was Hindu). I was the brahmin boy thoroughly enjoying eating the food – the sweets, the amti (a Maharashtrian dhal), the dhal-s …. In my own family, we were not religious. The only thing we had was an image of Goddess Saraswati – which I still have with me.

My father would come home for two months every year – in November and December. Traditional music was all around, from my mother and my father too, but I was not actively learning. My father would casually mention things like this swar (note) is like this; this raag’s vistaar (combinations of notes used to bring out the essence of the raag) is like this; this raag’s swaroop (soul) comes out this way; the particular sruti of the re in this raag is less than the sruti of the re in the other raag….

I was then into anything and everything. I would listen to the Jackson 5, Harry Belafonte, Jim Reeves and the Jazz Yatra, sponsored by Air India, which would happen at the end of the year. There was a guitar at home that I would play as well. I would take random things lying around and use them as drums. Many Jazz musicians who wanted to get a glimpse of Indian Classical Musicians and their lifestyle would come to our house – Don Cherry and Sunny Rollins, for example. They would listen to my father, uncle (Zia Farid’ud-din Dagar), mama etc.

In 1977, my father returned to India for good – after that he made only periodic short term trips to places like the Rotterdam Conservatory. He had been offered a green card in the US but wanted to settle in his own country. He had wished to train me then, but I was not too keen on learning. Once in a while, I would take his veena and play it, but it was just a game. He would never say “don’t touch my veena” but insisted that I had a bath or cleaned myself before I did.

My uncle, Farid’ud-din Dagar, stayed with us as well (until 1982, when he moved to the Dhrupad Kendra in Bhopal), and he too would have students home. There were students 24/7 – all pervasive music. That becomes a struggle – when there is an excess of something, you don’t feel like doing it because it is already there. And there is the overconfidence of youth – I felt I already knew everything – if someone sang something, I would associate it as ‘ye Radhika didi ka raag hein,’ (This is Radhika’s raag) etc. I never pondered on the depth of the music.

When did you begin pursuing dhrupad actively yourself and what was the impetus?

When I was in 9th or 10th std., my father asked me what I wanted to do. Music? Something else? I said music. He said, “I don’t see you doing anything else because neither are you studying well nor are you displaying interest in other things. You cannot take up a conventional job. At the most, you could open a paan (preparation of betel leaves and nuts with other additives that can include tobacco as well) shop.” I replied, “No, I don’t want to open a paan shop.” My father continued. “But if you want to do music, you should feel that from the inside. I cannot tell you to practice.”

I had always been a rebel. You could never bind me to sit down and do anything. It had to come from within me. But I wanted to do a single thing and something on which I could spend my entire lifetime. I also did not want to be tested on it or to have to prove anything in it. I found music to be open ended – without a beginning or an end. Wherever one is, one is happy – one does not have to prove how big or small one is. What really helped me was my father’s attitude.

“Don’t worry about what your ancestors have done. Think of what you want to do. Whatever you do, do it not with the mind but with a full heart. Don’t worry about where it is going. Just do it.”

– Zia Mohi’ud-din Dagar to his son Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar.

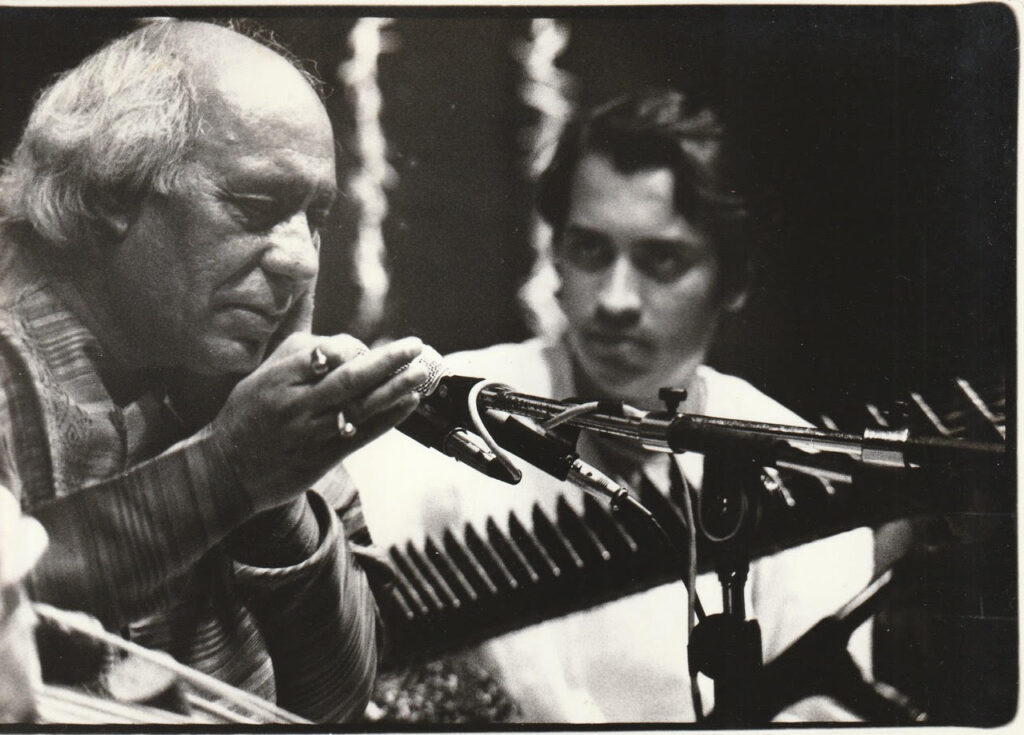

In 1986, my father and uncle performed over 40 concerts for the Festival of India in the USA – as a duet – my father on the rudra veena and my uncle on vocals. These were two people who rarely agreed on anything usually, but here they worked together demonstrating that they were just two different viewpoints of the same ideology. It was a conversation between the two brothers – one like water, the other like fire. I went on that tour with them, dropping my 10th board exams, and played tanpura for all those concerts. That was when I started realizing what this music really is. When I came back, I told my father that I wanted to learn music.

He acceded. I asked him, “What should I do? Should I play the sitar, the veena or the pakhawaj? Or should I sing?” He looked at me and said, “Play the veena.” Then, I said, “I want to learn from you.” The aspiring student has to say that. Just because he is your father, he will not ask you. He replied, “I have conditions.” I said, “I am ok with anything.” He asked me to first listen to what they were.

“Firstly, from today, I am not your father. I am your Guru. Whatever I ask you to do in music, you will do. You will not act on your own ideas and impressions until you have reached a level of understanding yourself. Secondly – you will never use your vidya (knowledge) to shoot down anyone in life. Thirdly – never touch alcohol.”

– Zia Mohi’ud-din Dagar‘s conditions to teach his son Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar.

I agreed. That conversation got over. I still did not do anything. I did not learn. But I got more involved. I listened more attentively to what he said seemingly casually. The re of Abhogi in relation to re of Bhoopaali; the re of Yaman; the re of Bilawal; the small details like the syllables he would use – ta, ri, na etc.

How and when did you learn the basics of the instrument?

Between ages 7-9, I learned sitar from my mother – just as a hobby class. The daughter of my father’s student was also in the class. We learned together. It was purely mechanical – like parrots – the content of standard classes. We went from raag to raag. It was happiness but no real understanding.

Did you play on smaller sized instruments as a young child?

No. I always played on the full-size sitar. There was a small been (more on the been below) at home, but no, I wanted to play my father’s veena. The tonal quality is very different in smaller instruments. The size of the instrument also changes your thought process on how to play.

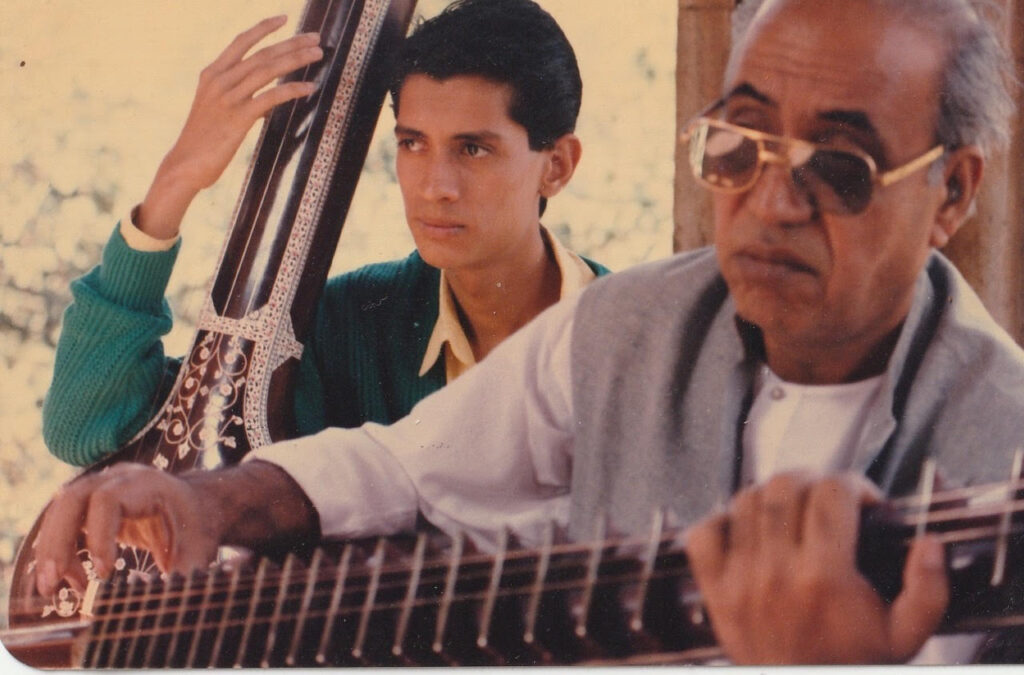

In Mani Kaul’s film Dhrupad (link above), I notice you are holding the veena in the traditional fashion, before your father switched to the ‘saraswati veena’ style of positioning the instrument. (Mani Kaul was a student of Zia Mohi’ud-din Dagar.)

That is a ‘been’ – the older model of veena. It weighs about 3 kilos. You play it with one thumba (gourd) over the shoulder. That instrument had just come into the house a couple of days before the filming of that sequence and my father asked me if I would play it. Mani Kaul told my father, “Let him play while you sing for the opening sequence.” I never played that veena after that. I preferred the colour of the sound of my father’s veena.

Circling back to how you got started on serious training.

I joined St. Xavier’s College in Bombay. They had an Indian music group there where I volunteered and got to listen to a lot of music from many famous musicians. One day, when I was in the 2nd year of my BA, my father asked me, “Do you have to go to college today?” I said, “Yes, I have to.” “Why?” he asked. “I have an exam,” I replied. “When you finish, come back home immediately. There is work for you to do,” he said. When it got over and I stepped out, I found a neighbour awaiting me who said my father had been hospitalized. At that moment, I knew he had passed away.

Several days went by. My mother was very worried about me. I had never played or practiced or learned from my father – yet, all his work, a huge universe of information, was out there. So many things my father said kept echoing in my head – Jaijaiwanti ka nishaad, Desh ka nishaad, which nishaad is used in Saarang, which one is used how. The only way to understand it was to sit down and practice. One day, I just began from scratch – with the sargam (notes) in no particular raag. Then, for 6 years I played only Yaman and raag-s Megh and Malkauns.

Only three raag-s for 6 years? But how did you even know what these raag-s were and how to approach them?

Yes – only three raags for those 6 years. My father had taught me skeletons of raag-s to work with – in the Dhrupad movie, you can hear him sing that of Malkauns, for example. Similarly, those of raag-s Yaman and Megh were given.

Would he play it or sing it?

He would always sing it to me. He said if he played, I would merely copy and that a copy would be very boring.

How was the art of improvisation inculcated?

He would teach the sthaayi (the first few lines of the composition) which I would learn by heart. He said just keep playing. I kept playing the same thing – for 6 or 7 weeks. One day I found I was playing an aalaap for 20 minutes. I wondered where it came from. My father said it was from the sthaayi. However, he added, “You have only improvised it mechanically and technically – it is yet to sound like Yaman.” So I held on to it. It was the seed that would then grow to give fruits and flowers. One seed is enough.

I was also curious about other raags. I would ask my father – what is Kaushi Kaanada like, what about Basant Mukhaari etc. He asked, “Do you want to be a coolie or a musician? Why are you carrying all this weight on your head?” I said, “What if I am not able to play those?” “Don’t worry,” he replied. “If you can play Yaman from the lower octave (mandara saptak) to the upper octave (taara saptak) correctly once in your lifetime, your work is done. This is not a market where you are selling raag-s. The purpose is to understand your life. The life is connected to the work. The work is connected to the life. They will fuel and facilitate one another. If you clear one aspect, others will start illuminating themselves.”

And truly that is what happened. After Yaman, other raag-s started opening up to me.

Do tell me more about learning from your uncle.

It was after 7-8 years of studying on my own that I approached my uncle. In that period, Pushpraj Koshti-ji guided me (he still does – we regularly converse). He is a surbahar player who learned from my father from the time I was 4 years old. He would encourage me and make me play for long hours. I would ask him questions. I was still playing just the three raag-s. He was very patient yet would push me a lot.

My mother made a provision for a monthly baithak (informal house concert). There was never a concept of preparing for a concert. The practice is always to better your work – not for a concert. But, because of the baithak, I would practice – try and prepare something in my mind. It was my mind that had to be ready. One plays whatever comes to mind that day – but an impending baithak gives a concreteness to the playing.

“Even though they were brothers, of the same genre, the same ideology, my father and my uncle had completely different ways of teaching. My father would give a seed. My uncle would give a gunny bag full of material and load it on your head. My father would say it very gently and spread it out. My uncle would go into the nucleus, destroy it and plant another tree.”

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on his father and uncle’s different approaches to teaching.

To transfer from the one to the other was a challenge and difficult initially. However, when I realised both were actually the same, the learning happened by itself. I understood what he was saying. “Veena me aese bajta hai, isko gaane me aesa gaate hai (In the veena, it would be played like this; in vocal, it would be sung this way).

There is this saying that is apt. ‘Naabhi ke kamal se teen moorthi bhai, bin jaane sohi narak bhogi’ which roughly translates to ‘From the navel, three moorthi-s (deities) are born – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. If you look at them together, it is hell; but if you perceive them as different, it is worse.’ Many students did struggle in learning from one and then the other between the two brothers. They saw it as two different things. To me, it seemed that my uncle was saying the same thing but just differently.

So what was a lesson like? How long would it be?

Whether it was my father or uncle, lessons were just 10 minutes. Uncle or father would come and say “ye bajao, usko aise bajao” (play this, play that this way) and they would leave. We would ask them why they did not sit with us. They would reply that we should play/sing something so moving that it pulls the Ustad (maestro) out to come and listen.

It was difficult to comprehend what my uncle was doing because it could be very wild. He would often begin from where it seemed impossible and then bring it all in.

Sometimes lessons would be across the table – informally over conversations. At certain points of time, the student’s mind is open – it is like seeing an opening and dropping something into that. At such times, it registers at once and resonates.

When you first started practicing in earnest – you said that was after your dad passed away – when you were 20 – how many hours would you spend practicing?

In the beginning, there were two things I wanted to do. Firstly, to develop an understanding of the fret-board, where even if I closed my eyes, I could see it in my mind’s eye. The other was to get in the habit of playing for long periods at a time. So, initially, I would sit for 4-5 hours at a stretch, ignoring any pain or tiredness. When the pain is first felt, if you push past it, you can go on further. We should build our stamina to a point where no discomfort should show on stage.

I started with sargam – not any particular raag. That was to understand the instrument, get the fluency in it, know where you are pulling from – to get the basics right.

So you had to teach yourself these skills?

Yes, there is a lot that one has to learn by oneself. But if you have spent time with the Guru, you have direction and a path to follow.

Was it because you grew up in such a music-filled environment that you could make sense of those ten minutes of teaching?

All the students had the same kind of training. Talking and sitting together transferred more music than teaching. Just spending time and being with your Guru passes something on to you that is unexplainable. I still don’t know what it is, but many things were passed on in that manner. Something would get resolved. Farid’ud-din Dagar would be sitting quietly but he would know where each fly and mosquito was. He would know what was in the mind of each of the 6 students in the room. There is a lot to be learned by just spending time with your Guru without a reason. My wife, (dhrupad vocalist Pelva Naik) who learned from my uncle, says she now realizes what the value was of just being with him. He made you feel alive. It was as though you were in this big glass globe which was full of music. And the music just kept reverberating.

How did you take those few minutes of concentrated instruction and interpret it yourself? I am assuming each minute would have required hours of your own time to expand on and do full justice to.

It took time. It grew in parts. Only one section of it would grow. Sometimes one part would grow, stalemate and then the next year, the same section would grow again. At times it would grow startlingly quickly. Sometimes it would be so bad that I would be in the pit-hole – nothing would come. The depths of depression.

Edited for sound by Sri. Madhu Apsara. Title Photo: Sri. Nick Haynes.

So there were times it felt impossible? When you felt overwhelmed?

There have been so many such occasions. I have cried like a child in front of my father. I have said, “Nothing is happening. I am going to break the veena.” My father would say, “You have no patience. If you bang your head on the wall, nothing is going to happen. Just wait. Let go for a bit and then return to it.” How could I let it go, I would ask, for there was nothing in hand to let go. “For 2-3 days, don’t do any music. Then get back to it,” he would say. I would do that. Then, something else would come.

But so many times it would feel that this was not possible in one lifetime – not even in two to three lifetimes. Sometimes, I would say I am not going to touch that instrument because the most atrocious music was coming out of it. I would feel that a passing ant that heard it would fall dead.

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on the periodic feeling of futility while learning the art form, particularly in the earlier stages.

“Be patient,” my father would say. “I have lost my patience,” I would retort. My father would patiently respond. “You have to wait. This is not property that is given to you by ancestors. It is the anubhuti of Goddess Saraswati. It requires a lot of patience. Sahan shakti. Increase tolerance. Increase patience.”

Did you learn vocal?

For many years I did not. When my uncle joined IIT as a visiting professor about 12 years ago, I started sitting with him and paying attention to the vocal aspect, how the voice was used, how one sang – and how to bring the vocal into my jaala (fast, rhythmic yet free-flowing improvisation). Now I am trying to do so in the aalaap.

Do you try to play such that the syllables used in vocal are reflected in the strokes of the veena?

That is what I am currently working on, yes.

What about strings snapping? Did you know how to replace them? And the filing of the bridge (jawaari)?

No, I had not learned any of that. My father would not let me do it myself – but I had watched him do it. I did know that strings needed to be routinely changed every three months – because the tension is affected after that and you don’t want the instrument to act up in a performance.

The bridge was trickier – nobody wanted to handle the bridge of a veena because of the many superstitions surrounding it – one’s own death, death of family members etc. I just experimented on that myself. I destroyed some bridges in the process but learned a lot. If one goes to a concert and the strings are not in its best of tone, it is not a good thing. I learned the basic aspects and there were people who told me more about what to look out for.

My father knew to do every aspect of it – right from finishing the veena, to the small decorations – everything.

Would it be correct to say that you were inspired to pursue music because you were not forced to? It was around you but your parents did not push you to?

I think it was reverse psychology. Before going somewhere, my father would sometimes tell my mother, “Don’t let this boy touch the veena-s. He spoils them.” As soon as he went, I would take the veena down and start playing. Even whilst teaching, if there was something he wanted to tell me, he would tell the person sitting next to me. I would wonder – why is he telling him this? It was utterly irrelevant for him. He used to do this with everyone. He used a lot of reverse psychology.

I have a boy here with me who is a sculptor – he makes veena-s. He told me his Guru would do the same thing. Later, we realise it was for us. Sometimes when things are said directly, one absorbs it less than when said indirectly.

On the Dhrupad Gurukul, teaching and training methodologies.

It seems like the entire family, particularly your parents, had to sacrifice a lot to make the Gurukul a reality.

The Gurukul was built in 1982 and is in Palaspe, near Panvel. My father used to commute to the Gurukul every weekend with some students before returning to Chembur again. My mother and I would also come with him. There was nothing in the village then – we used to bring everything we needed with us each time. It is exactly 37 km from Chembur where we resided, but would take 2.5 hours travel time, as there was no bridge and we had to come via Thane.

I personally did not make any sacrifice. But my father had to be alone frequently and it was a lot of work for my mother. But that was what we, as a family, wanted – for this music to remain and to be sustained.

My father came to Bombay after going to Delhi and Calcutta with literally nothing but the clothes on his back. He had no instrument with him. He was sleeping on the road. He thought Bombay would be suitable because it was a city where work is God. He borrowed a sitar and did work in the film industry to survive and some teaching as well. When he got more students, he left cinema because he did not want to change his work to fit others. My uncle joined him soon after too.

The seminal moment was a concert at one of his student’s homes where the brothers played a sitar duet all night together. For that, they did not get paid even 5 rupees. It was a period of tremendous financial strain. That day, my father made a decision. “There is no respect for this. We will not play the sitar any more from now on. Farid, from tomorrow you start singing. I will play the veena. We will rebuild from scratch.”

So Farid’uddin Dagar Sahab also played the sitar?

Yes, he began with the sitar and had also learned surbahar from my father.

The ideologies in the 1970s were very different. There was a huge influx of pop culture – the Bee Gees, ABBA, George Harrison, bell bottoms, western disco – those were the in-things. Nobody wanted to listen to dhrupad. “Why are you doing it, Dagar Sahab? It is a dead art,” they said. My father would respond that he was doing it for himself. He was told that if he played the sitar, people would listen to him. He said he was not interested in the sitar. He was very clear – “I am interested in the veena.” Where in other concerts, there might have been 500-700 in the audience, my father would have just some 20 or so. But he always played to the fullest – never ever holding back because of the lack of people.

Financial difficulties meant he got married only at the age of 45 or 46 and lived very sparsely – just 4 utensils and they slept on the floor. Then one day, a lady, Mariam Shastri, came from the US who introduced him to a university there. And a gentleman named Bengt Berger – who recorded my father in 1968 for the Swedish market. That gave him hope. “I will go abroad and teach and earn,” he thought.

Your father’s going abroad, it appears, was dictated purely by financial needs.

Yes, it was only necessity – he did not want to go abroad. He loved India and liked being here. For 8-10 years he was in the US, visiting India only for a couple of months each year. After 1987, he would go for 2-3 months each year to the Rotterdam Conservatory.

How does The Gurukul operate now? Do you have residential students or visiting ones? Do you have teachers other than your wife and you?

The Gurukul has always been a home of the Guru first and then also an in-residence learning facility. It is a home and the relationships are tight and close. But it is anything but an institution. ‘Dhrupad’, as it is called, has been a home for many students to come and learn. There is no syllabus. There is an awareness of certain discipline being practiced in order to understand this art form but it is not regimented. Expectations from the students are patience and commitment to learning. We have about 8 to 10 students roughly in and out. Some are residential, some come for shorter spans of time and some who live around the city come in for a day a week. We are not looking to increase the quantity but to spend more time and create quality students. Not all would be performers. In fact most of them will not be. We need some who will teach and then those who will guard and keep a check on the others in a positive manner, thus keeping the music above all else. Whether we will succeed only time will tell. But we are determined to be on that path.

Presently besides Pelva and myself there are no other Gurus here. Between both of us, we share the duties of running this place both administratively and economically as we are teaching for free on the premises.

Could you tell me about voice training in your school of dhrupad?

Between 2.30am and 5.30 am when the sushumna naadi (considered the key energy channel in the body as per some schools of yoga) is awake (the voice is facilitated to go low at that time), one should do kharaj saadhana – the word kharaj comes from shadaj (shadjam or the note Sa) actually. Trying to touch the lower sa in your octave (G# suggested for women) to the middle octave to the lower pa and slowly back to the lower sa. Try to hold your breath to as long as possible – a minute is good to shoot for. Another exercise is the murchana – s r g m p d ns :: s n d p m g r s, r g m p d n s r :: r s n d p m g r, g m p d n s r g :: g r s n d p m g and so on. This should be done in three speeds – slow, medium and fast. We sometimes give a small palta – m p d n s r s n d p g m p m g r s n d p, perhaps with a little bit of gamak in that – not to go above the pa until 10 am. Then higher notes up to the upper ga and as low as they can go. Then you practice two lines of the sthaayi of an aalaap and then a composition putting taal in the hand – no percussion. Then two lines of the aalaap again and again for 1.5 to 2 hours without any alteration. They do that for a couple of months and then we teach them to improvise. We do two-three raag-s in 7 years.

What was your uncle’s voice training like?

He would wake up at 2.30 in the morning. He thought that since he did not do arduous work like break stones for a living, he did not need more than 4 hours of sleep. The students would also all wake up at 2.30. So, from 2.30 or 2.45 am to the time when the sun would rise up, they would do the kharaj saadhana. That gets the voice to go lower and increases the lung capacity. Then after a break, they would go back to practice – usually compositions. This practice means that even if you have an ice cream or you catch a cold, it will not affect your voice. You don’t have to do anything to be careful about your voice.

There are no dietary restrictions, then?

No. I have even seen Ustad (Farid’ud-din Dagar) have several ice creams right before a concert.

Was exercise a part of the routine for well-being?

All of us used to play games like badminton. We used to play outside for 6-8 hours and then come back in and practice those days. Now, students have to be told to do these things. They are always on the laptop or phone. So we tell them they should do yoga – trikonaasan, bhaddakonaasan and surya namaskar.

Do you do any exercises yourself to ensure the health of your back, shoulder etc. for playing the veena?

Concerts get over so quickly these days. Often within an hour. It was in Darbar (a festival in London, England) that I did a 4 hour program. Things have changed now. In the olden days, even juniors got 2.5 hours. There would be three concerts in the night. The senior musician would come around 8.30 pm or so and go up to 1.30 or 2 am and then the next one would come and go until 6 am.

That probably allowed for singing a gamut of raag-s – evening, night, early morning etc. Now almost all concerts are at the same window of time in the evenings.

Yes, organisers are worried that people will not come if they keep it at any other time. Even the musicians are worried that the people will not come. I did not see the musicians of old worrying about people coming.

Do you abide by the timing aspects prescribed for raag-s?

I do abide by them. My personal opinion (not based on readings) is that the timing theory has come from the tanpura. When you tune a tanpura in the morning, you tune the joda (the middle two strings) then the pancham and the kharaj – at sunrise, the pancham and the kharaj differ – the sa goes higher and those two go lower. The Bhairav sa in the morning is on the dot, after that the next Thodi sa is slightly higher; if you go into the afternoon, the sa reduces. Then it increases, then goes lower again at night. I think this is the reason times have been prescribed.

If you don’t apply the notes of Darbaari properly, for example, the ga and the da will start sounding like a morning raag when it is actually a very late night raag. And I have noticed during certain seasons, certain raag-s strike you. During Basant, raag Basant will come to mind and Hindol and Purvi too. Something changes with the weather.

Please tell me more about the saadhaarani geeti.

It is a combination of all the other 4 geeti-s – the suddha – straight notes; the binna – more gamak oriented; govarhari – small meend-s (glides) here and there; the vegaswara – the Carnatic type – notes in fast succession. In each of these geeti-s, it does not mean only those specific types will be there – it is just that those will be the majority. Saadhaarani uses all of these in moderation – it came to be known as the Dagurvani because it was practiced by a group of Daguri brahmins in a village outside Delhi in the 13th century. But anyone could practice it. Not just a family member. Tradition is not the musician. It is the lineage of thought – anyone who abides by the lineage of thought is part of that tradition.

This is a very important point. Because people take ownership of their traditions – saying ye hamara gharana hai. You are following a lineage of thought. It does not belong to you but you are practicing it.

Interesting that you should mention that. I have heard that within gharana-s there are aspects taught by Guru-s only to family members and not outsiders – even if they were to learn from the same Guru.

You are right. That was frequently the case. Outsiders were treated differently. But if we don’t teach what we know, we will forget it. If you want to save the entire repertoire, you have to teach it to more people. With gharana-s who do not spread it, the lineage will end or end over time.

Is that why the Dagarvani is the preponderant form of Dhrupad now? Because it was taught extensively?

Yes, it was taught freely to everybody. That is why it has survived. My grandfather would say even if it was the size of a grain of rice it should be given away. We were to never worry if we would have enough – more will come. Withholding information is the biggest crime. One cannot give that information if that student is not ready for it, of course. But if someone is ready, you should give it away. Give it in a way that they can understand it later.

That requires one to be free of ego, or free of insecurity.

It is the only way for the gharana to survive. Even recordings cannot do anything. It has to be passed from one person to another.

What is the training routine in the rudra veena?

On the rudra veena, we start with murchana-s right away. One routine is pa da ni ni da pa; da ni sa sa ni da – we try to build the strength in the fingers – for pulling the strings etc. Then, we immediately take them to the sthaayi in the aalaap. We vary the sthaayi slightly, to adapt to the natural inclinations of each student so they don’t struggle too much to get it. Each student usually gives an indication of how they want to go.

Looks like it is a very fine line for a teacher to challenge the student but not demotivate them.

It is. The student should not feel that I have to put in a lot of effort in the beginning – we go according to their nature – we should not force it down their throat – then they will not want to continue. There is never just one way of doing anything.

Do you still follow the three-raags-for-six/seven-years regimen for your students now?

Absolutely. I make it very clear upfront. “I will teach you everything but I need so many years and so much riyaaz (practice) from you. When you are doing music, the Guru is the biggest tyrant. Please listen to me.” As and when they complete one aspect, I will give them the next aspect. I also tell them not to ask their parents to mediate for I will tell them nothing. I tell the parents not to ask a single question about progress for seven years. Students are free to do what they want in their personal lives.

We teach free of charge at the Gurukul. We look after them and feed them. Some spend considerable time. Some are working. Others are studying. I insist that they go to school and college – they have to be aware of the outside world. Such students come once a week. When they do, they spend the whole day with me. They are welcome to come in between too, if they like. Because of the pandemic, we call one student a day. Students can and should ask any questions and feel free to make all mistakes in practice.

“We want to focus our training on three different kinds of students – one who will practice the tradition, a second type who will teach, and a third who will understand the tradition, talk about it, be a watchdog and an important part of the discussion and discourse with the practitioners of the traditions. It is very easy for practitioners to inflate their own heads beyond recognition. We need people to keep the others in check.”

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on three types of students.

In the evening, we do online classes – a different thing altogether.

How is it different?

It is our bread and butter. We teach with the same commitment but most on the online platform are casual learners. Of course, there are some serious students we have unearthed in the online medium too.

Who is the ideal student? One who comes with prior knowledge of the music or one who knows nothing?

“The ideal student is one who has had no prior training but can distinguish between the different notes. If they come with previous knowledge, we have to work on erasing all of that. Also, the ideal pupil is not too eager but willing to follow the path patiently.”

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on characteristics of the ideal student.

Some of the students I have for the veena do not even know what music is – they come from eclectic backgrounds – some don’t know the difference between sa and re but I have agreed to teach them. As long as they spend time with me, I will spend time with them. One or two will come who will learn and practice the form. It is a good learning for us – different students teach us about attitudes, different ways of expressing and experiencing our music.

Do your students come to learn veena or vocal?

It was entirely vocal earlier. I have one student who came from Thirumalai – Venkatakrishnan by name – he has been with me for eight years. He is almost ready now. He is one of the bright ones. After the collaboration with AR Rahman (titled Harmony on Amazon Prime), which many people seem to have seen, there has been more recognition for the rudra veena – people don’t call it a tanpura anymore, for example. I have had some new students now for the veena too, and three are girls. I am really happy about that. After all Ma Saraswati is female. I only take students who will take the time and the interest to learn.

Do all your students have to learn both vocal and veena?

The students I have now are mostly beginners who do not know anything about music, so, no. If I play a note on the instrument, they will not know what it is. I have told them we will take a journey together and we will get somewhere. Some understand more than others. The others sometimes ask how they proceeded. I tell them not to compare. We will get there gradually.

Some students can take even two years to get in tune. Once they can hear themselves as in tune or off tune, they will proceed further.

I am letting them try and letting them be.

On the veena – the instrument, how it relates to dhrupad itself in the Dagarvani, and its symbiotic relationship to and with vocal.

I read that your grandfather was against your father altering the veena. Why?

He was against my father playing the instrument itself because according to tradition, those who are vocalists should remain vocalists while those who are instrumentalists should remain instrumentalists. The idea was that an artiste of the vocal tradition switching to instrumental means one is treading on somebody else’s toes. But my father was very ziddi – stubborn. Then finally my grandfather gave in and said you can play. This was when my father was 8-9 years of age. By the time he was 16, he was already proclaimed an Ustad because he was so profound in his raga delineation.

So, was the veena looked at only as a tool to enable better singing and understanding of vocal?

Yes, mainly, Correct. Later, when it entered the courts, it began competing with the rabab (a lute-like instrument common in Pakistan and Afghanistan) and began developing various techniques.

There are ten lakshana-s each of vocalists and veena players – eight are matching in both. The gamak and the hudak are not possible in veena.

“The veena teaches vocalists which syllables can be sustained and for how long. For it is not just a question of breath control – just because one is physically able to do something does not mean it is aesthetic. The timing of a phrase and where to cut the phrase is very important.”

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on how the veena contributes to vocal

There is a framework – shastriyata. The veena teaches this very clearly – where to cut and how to cut a phrase. The veena has lesser resonance, which compels you to put a stroke somewhere in between. It makes you take note of the weight of the stroke, and which finger you are going to use. Between sa and komal re, you can see a difference of 7 swar bed-s – komal, tam komal, tam tivra komal, the base note, tivra, tam tivra, tam ati tivra. One can clearly pull a veena’s strings and see which of these should be used for which raag. It is said that if the voice is the king, the veena is what measures it.

The veena is a yantra – not an instrument. When you strike a veena, innumerable sruti-s (ananth sruti-s) are heard on it. If I strike a string and I put a hand under it, you will hear it change by half a sruti (I don’t mean it as a swar). In other words, the veena can clearly demonstrate where each of the notes are, the ideal duration and timing for each and how to cut a phrase and how much weight to give it – all of which can be transferred to singing.

I hear the clear influence of the veena in vocal particularly in Jod and Jaala.

You are right. There is. The faster, more rhythmic aspects definitely take from the veena. Generally speaking, the veena takes from the voice but with the intricate and finer nuances – the swar bhed-s, for example – the voice takes from the veena.

In our family, there are two broad lineages – one is that of my father and uncle, their father Ziauddin Khan, his father Zakiruddin Khan, and his father Mohammad Jan Khan. The other was Mohamad Ali Khan (brother of Mohamad Jan Khan) > Allabande Khan > Nasiruddin Khan > senior Dagar brothers (N. Moinuddin and N. Aminuddin) and Junior Dagar brothers (N. Zahiruddin and N. Faiyazuddin)> Wasifuddin Dagar (son of N. Faiyazuddin).

Mohammed Ali Khan used to play the sursringar which is like a bass sarod – what Baba Allaudin Khan used to play. But after him, that branch of the family has not played an instrument. We, on the other hand, have continued with the instrument uninterrupted. Therefore, we adhere to things like the baarik, suksham notes etc., stemming from the veena influence. In a veena aalaap, you will have the sthaayi, antara, aabhog, sanchaari (parts of delineation of a raag in a typical dhrupad performance) in a very proper manner – we begin in between, go to the lower kharaj and start improvising. In the gaayan (vocal tradition), you have the aarohi and avarohi, you will go forward then backward then forward again.

The words and syllables were mostly fixed by my grandfather. Let us take a simple phrase – a re na. By adding more syllables a re, re na, ri ra, re na, it becomes a compound phrase. Keeping that grammar in mind, we play in the veena.

I think one cannot separate veena and the voice. They are parallel – 50-50 – and feed off of each other.

Your father made significant modifications to the veena. What motivated him to do so and what were these changes exactly?

The been was the predecessor of the veena. My grandfather sang and played the veena simultaneously. My father felt that the veena did not match the sound of the vocal in the lower octave. That was the primary motivation to modify the instrument. He wanted the veena to match the lower octave of the voice too. A second aspect was it needed more resonance, a deeper and heavier sound that would match the way the gaayaki was defined – to better reflect the words and how they were used.

When he was very young, my father spoiled a lot of veenas, trying to make many changes. Despite getting badly scolded, he continued doing so. My grandfather then explained to my father what he was looking for and how it could be achieved. The dandi (stem) had to be bigger, the thumba-s (the hollow, bulbous gourd resonators) had to be bigger. He started working on this.

These were the things he did:

- He switched the dandi from bamboo and thoon wood to teak wood which had less volume leading to more resonance.

- He put a peacock with a chamber inside it. The bridge has an opening allowing the sound to go beneath and into the dandi– increasing the resonance.

- He put a vaasuki (a dragon) in the front – it breaks the tension of the wire – and also makes sure that the dandi does not bend – in the earlier veenas, the dandi would bend.

- He decreased the heights of the frets so that it was easier to slide and easier to pull.

- He put in two bigger thumba-s.

- He changed the jawaari (bridge) bringing in a deeper tone to the instrument

- He made a groove on both sides of the frets and tied it with moonga thread – this made the instrument easier to travel with. Earlier, the wax holding the frets would melt or soften with temperature and humidity, making the frets move.

- He did a lot of work on the gauges of strings too (which I discovered after his death). He used a #7 main string, the chikaari-s (sympathetic strings) were #3 and #4, the jod was 0.70 mms (micro-millimetres), the pancham was 0.90 mms (the maximum you could get in India). From abroad he got a 1.20 mms 18 number string.

With all these changes, the weight of the instrument went from three to ten kilos straight away. Holding it in the conventional manner thus became impossible. My father said that nowhere was it dictated that one thumba had to be over the shoulder – what it had to be was in the position of the shoulder. So now, we bring the shoulder down to where the thumba is – similar to how the saraswati veena is held. Now, since we have a deeper tone, and the veena has also come down, all the weight now goes on the left hand making for more nuanced left-hand technique – vs. the very pronounced right-hand technique employed in the earlier model of the veena.

My father went to Nithai Babu Kanhai Lal in Calcutta and they made this veena together in 1963. Then he practiced on it, played on it and then slowly took it to concerts. All these changes were dictated by necessity but were very much within the framework – to make the instrument much closer to the voice.

Did he face criticism and objections for this redesign?

All the time. People said it looked like a very nice piece of furniture. Who will listen to this, they scoffed. He was ridiculed constantly. Even his AIR audition was a big thing. Thakur Jaidev Singh (a renowned musicologist and a Padma Bhushan awardee) said I will do a recording of yours and take it over without telling them who the artiste is. The panelists said he should be given the Top Grade. Top was given only after 6 months at A Grade – so that was what happened. Once he went abroad, he got domestic validation.

I notice that the rudra veena in its present form has thumba-s that can be unscrewed. Is that a modern development?

No, that has always been the case. In fact, in some of the old instruments from 150-200 years old, there are multiple holes in the dandi to allow for the thumba-s to be screwed on in different places according to the physical stature of the instrumentalist.

There are, in fact, so many varieties of the instrument. There is the sitar been. There is a folding veena. There is another one where the frets are like a saraswati veena.

How are the frets in a rudra veena different from that of a Saraswati veena?

The Saraswati veena has two walls of wax on which the frets are placed, and the frets are metal. In the rudra veena, the frets are made of wood encased lightly in metal and placed on a single mound of wax.

Have you made any changes yourself to the instrument?

No. What my father did was a huge leap. For the next four hundred years, I think we just have to understand this instrument and play it properly. I don’t think anything else is going to be possible.

You have performed with your wife. How was the pitch adjustment for that?

She sings in G Sharp and the veena is in G Sharp. So no adjustment was necessary.

The veena is always tuned to G Sharp?

Yes. Since my father adjusted the tuning, the pitch came down from E to G Sharp. In fact, when my uncle performed with my father, he would sing in G sharp and his voice would go to all the three octaves – from the sa in the lower octave to the sa in the upper octave. Similarly, when I played with my uncle, he would sing in G Sharp and not in D which was his natural pitch.

How did he do that? G# is an unusual pitch for a male, is it not?

Yes, but his voice training was such. He did his morning kharaj saadhana every day and he could reach the upper sa so easily as well as the lower pa. He said I don’t believe in a specific pitch. He would sing in D which was his natural pitch and at G Sharp when singing with my father. And there was no falsetto.

On misconceptions, spirituality, attitudes to learning, the ills in the art form and what Dhrupad has going for it.

Any artiste performing on stage has to possess a high degree of confidence. How does one juxtapose this confidence with the inherent vulnerability that every human has?

What we were taught is you will play whatever you have been taught. Only that and nothing else will come out, because we are not God. If it is good, bad or ugly, let it be so. If you are walking and strike a pebble, you will not turn back – you will just push it aside and move on. It is the same thing here. If you get stuck or make an error, you move on.

Secondly, you will play only what you have understood (which can be different from what is taught). Thirdly, you are sharing something only you know and that you have an opinion on.

We all say music is a spiritual experience. If you are a pujari (priest) at a temple, you are going there for God. A visitor to the temple too is going for the God. Should the pujari look at the visitor before doing the puja? No, right? Actually, if you are vulnerable, the best music will flow.

So you have never felt any stage fear?

No. Because I will frankly admit that a bad concert is a bad concert. I will know it myself and I will know what I need to work on. When I listen to a musician and it is a bad concert, I don’t judge them. I will listen to 7-8 of their programs. Anyone who is on stage has something to offer or they will not be there. (Unless it is a small child you are encouraging. Children are fearless.)

Not all audiences understand music. The audience might still say a bad concert is good – they might like you or want to encourage you or are there just because they want to listen.

“It is our responsibility to understand our work and educate them on what that work is. In other words, I should be giving the audience what they should know about this work – not what they want – so they understand this work better.”

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on the artiste’s responsibility to educate the audience.

How does one move from mechanical playing to becoming a concert level artiste?

When you feel you have something to show, you will show it. Just as how if I have done a good painting, I would want to show it to you. The concert is but one element in one’s tryst with music. In the five fingers, it is the little finger. We should not put it out of its place from the many other aspects. If you are on stage with a senior vidwan, you are there to learn. He will take care of you. If I am on stage with Umayalpuram Sivaraman-ji, I should merely focus on doing what I can – he will take care of the rest. When I played with my uncle, I was not worried about making a mistake – I am a human being – I will think it out and work on it.

When you prepare with a concert as an end goal, you will only do so much. On the other hand, when you prepare the work, it might end up being more, or less, that what you might have expected. In that mystery, you discover a whole lot – your vulnerability and so much more. I would actually not enjoy a concert that went perfectly. When somebody is trying to do something, and they make a mistake and go back and fix it, that gets me intrigued.

When you were learning, did you learn the raag or the composition?

I was never taught taal. I was just told, “You know chau taal, no? It is 12 beats. Make your own composition – do it. Just try.” It was always a case of jumping into the deep end and learning to swim. “Do whatever you understand. First try it yourself and then I will help you.” My uncle would sometimes mention a composition and very lightly allude to where to cut phrases and how to look at it. I have a friend, Ramkumar Iyer, who would say, “Where it is beautiful, just leave a fragrance. Don’t overdo it.” Some do amazing taal patterns – if you like that, you should do that. My personal focus, though, has been the aalaap and not the taal.

When you play a composition, do you have lyrics in mind or do you think of it as a sequence of notes since you are playing an instrument?

Both. If my pakhawaj artiste has played for someone who learned from my father, like Uday Bhawalkar, for example, and he is familiar with a particular composition, I will play that. Otherwise, I will just compose a gat (instrumental composition) which will be on the spot, and tell the percussionist what I am intending.

Though one’s eventual goal might be to carve out one’s own niche, initially, just being able to copy the Guru authentically would be a goal, right? Because even that would seem a lofty ambition.

In the beginning, we always replicate the Guru and follow his steps exactly. It is the Dhruva taara (Pole Star) we are trying to follow. But after a while you realise that the weight of your hand on the instrument and your understanding of the idiom is your own and not identical to that of the Guru’s – we have to understand what that difference is and come into our own. It is not a trivial thing – especially because, we, as individuals, are constantly changing and we have to evolve with that.

It is a question then of how much time we have spent introspecting with the music?

Yes, exactly. It will not happen initially. But after you have quite some understanding of the music, you start thinking that way. It might take some 8-10 years. What do you sound like? How much can you retain in that framework and make it sound like it belongs to you? What is your opinion about that work? The fact is even if you want to sound like the Guru, you cannot.

It seems to me that you could have a concert without percussion.

Yes, and I have done that many times. At the Darbar Festival in London, I performed a 4-hour concert only with tanpura and no percussion. Even without percussion, I still think it is complete. One of our pakhawaji-s, Sanjay Agle, would sometimes gesture to me at concerts that he would not play at certain points. Seemingly saying, “It is going well. Let it be.” Mostly I like to end with just the aalaap. To me, that is what the veena is about.

Your father, you have said, would play raag-s (you had mentioned Malkauns) in ways that would leave listeners ruminating on its essential familiarity – yet elusive as to its exact identity. There are two schools of thought – one where it is felt the raag has to be clearly identified at inception without any mystery, and the other that keeps listeners guessing. Did your father subscribe to the latter idea?

Once he played 3 notes of Surdasi Malhaar – re pa ma – repeatedly up and down – different phrases – for 15 minutes. It sounded very familiar. Kaunsa raag hai, we kept wondering (what raag is it). But it was not possible to pin it down. ni da pa was not there. He did not play ma pa ni da ni sa (which could be in many varieties of Malhaar) at all which would have aided the identification. His point was that even within those three notes, based on how he handled them, it ought to be clear what raag he was playing. He never did this at formal concerts though – only at home and at informal baithak-s where students would be listening – as education – to increase awareness of minute nuances and inculcate focused, active listening.

My uncle too would do this. He would begin with 2 or 3 notes and expect his students to sing with him – but he would not say what raag it was. The students would keep looking at each other wondering what it could be. Once, when I was playing with him at a concert, he began Hem Kalyan. I had never even heard of that raag, let alone heard an exposition of it. How was I to play? I asked him, “Ustad, what is this?” He said, “Just listen to me and follow along.”

Being on stage and not knowing the raag forces you to explore only that section of the raag without even attempting to add a further note, right? Because you don’t know which next note is part of that raag? That would have been very challenging.

Exactly. It was. If we went to a fourth note – he (Farid’ud-din Dagar) would say, “Hey – aage math jaana” (don’t go there). I thought it was a beautiful way of taking me to a particular point and then opening me to a new aspect – not the regular form of teaching. To look at it from a different dimension and see what it reveals. It teaches you to be adventurous and approach the raag in a new manner.

We try to create space between those notes – different types of spaces – akin to a comma, accents, using different syllables…. 3 notes offer 9 combinations, yes, but we are not trying to do combinations. We are trying to get to the swarup (life) of the raag. It is not the aarohi avarohi (scale)– that is just the skeleton. Swarup is the soul. Each swar (note) is a fractal that should stand for the whole. Each note should be touched in such a manner that just that one note will reverberate with the entire raag.

It was not easy for us. But when he sang, it would show up the whole raag. When we sang/played with him, it would come. But when we tried to do it on our own, it felt like a slap on the face. It was just not happening.

You mentioned your father saying music required immense patience and tolerance. Do you see that translate into daily life?

Daily life, it is hard to say. But musically, it does translate – some things come automatically. Recently I started raag Bhoopaali (similar to the Carnatic Mohanam). I was so upset earlier about not understanding that raag – the dhaivat (the note da) was not coming correctly, and the position of the shadaj (the note sa) was not right. Now it is resolved. It takes time for some things to be absorbed. A certain maturity is required.

Also, you can never say you know something. It might click once but not the next time. My father would say ‘sook bhognae ka saamagri’ meaning you have to focus on making the right kind of vessel to take things in – not control the things that go into the vessel.

In other words, keep the mind in a receptive state to take in whatever it can absorb.

Yes. With this attitude, we are free from thinking about concerts. We are free from thinking about money. It is art for art’s sake – for the romance of the art. If it is a bad concert, it is a bad concert. It is not the end of the world. It does not matter. If concerts are less, so be it. The biggest asset is you have the instrument which you can play at any time. A very nice thing to keep in mind.

But there is the very practical and inescapable fact of earning a living, isn’t there? How does one juggle the need for introspection to improve one’s music with the need to market oneself? Social media and all that?

I don’t juggle. I post on social media to make people aware but I don’t worry about how many likes or views it gets. In our house, we have not worried about money. At times, we have been so low on money, you cannot even imagine. My father said if you worship Saraswati and you do your music sincerely that you will never die of hunger – you might have less, but you will not die of hunger.

We do not think too much of what is going to happen. For example, I might not take up some concerts because they don’t remunerate well enough. On the other hand, I might do one for absolutely no money. There is no logic. When money is needed, it finds its way and it already knows when it is going to go away again. Goddess Lakshmi is fleeting – she will not stay.

I have taken many risks but not worried about being seen or heard. Too many are worrying now that if they are not seen or heard, they will be forgotten. You tell me – Mukta (T. Mukta) was there – I met her in the 1980s – she did not perform much at all – no one has forgotten her. On the other hand, you can give thousands of concerts and be utterly unnoticed.

When I say this to others, they say it is easy for me because I come from this family. Actually, no. It isn’t. Because of the family I come from, a single mistake will put me in my place at once. I have to work much harder and be twice as good.

I often hear, “In the beginning, I got many concerts.” Do you realise why? Because you did riyaaz (practice) then. The listeners want your music. Rather than focus on concerts we should focus on the music and increasing our knowledge of it.

There are some who just want to look at you too, of course – a completely different category. Such people will do anything – sell even the seeds. And this is not just in music – it is in all arts. If you want to play to the gallery, you cannot expect to go deeper into the music.

If 1000 people listen to music, 500 are listening to khayal, 250 to Carnatic and only 5 to dhrupad. I tell my students this – I guarantee you will not get money. You will not get concerts. But if you still want to learn for your happiness and satisfaction, I will teach you.

The word dhrupad is said to come from the words Dhruva+paada implying a fixed composition. So, how is it now such an aalaap focused style?

I don’t believe it ever meant fixed composition. The root ‘dhr’ in Sanskrit means to hold together. ‘Dhruva’ means changeless amidst change. Framework, rather than a composition, is the idea of the ‘paada’. The framework can be bent. It is like a bangle that is flexible enough to fit a 6 year old’s to a 25 year old’s hand. That is what it is – not what is commonly written of it, because most of the writers have not practiced the art of dhrupad.

When you practice it, you can see the openness. My wife and I are discussing this a lot these days. How it sets us in a certain direction. How in the olden times, the dhruva taara used to direct travelers – it did not mean that the path is fixed though – there are still multiple ways to get home. It is an opinion about a way of music. That opinion is the dhruva taara which gives a general direction – lending a certain kind of refinement.

We often hear that the point in music is to explore the space between the notes…. In dhrupad, one can actually hear this…..

That is because we slow everything down. It is like the gaze – if I turn my eye very slowly around the room, I get a different perspective of what is in the room compared to a quick glance. Extreme detail in a slow speed – you can see the note going and you can see it coming back. You will see this in miniature paintings too – going in and coming out – all 16 schools of miniatures reflect this. How do we create space? How do we create time? How do we produce newness within a framework that cannot be changed? How does our nature, swabhaav (habits), affect this and how do they get reinvented in this process? What do we want to share with the people?

That what is crucial is the process of learning and being with the music was already immersed in my mind. Now, for instance, I am thinking of Adi Basant aka Dakshini Basant (reminiscent of the Carnatic Vasanta – hence the prefix Dakshini). I find the Dakshini Basant more authentic than Basant itself – I am trying to explore it, to get into it and see how it is different from our own Basant.

We generally practice the saadhaarani geeti (Interviewer’s Note: Baha’ud-din-ji explains this in detail in an earlier question above) geeti refers to styles of singing, but we should understand where and how and where to employ the other geeti-s. So, we study that. In our repertoire, we sing raag-s like Suha, Vardhani, Vaagadishwari, Abhogi etc., that are sung in Carnatic as well, for example. I really enjoy exploring how these raag-s are treated differently in that style.

Does dhrupad have rules that only certain raag-s may be played?

No. There are no rules there. In fact, one of my father’s cousins, Fahim’ud-din Dagar, knew a composition in the raag Kanakangi in Dhrupad. Sayeed’ud-din Dagar in Pune knew a composition in Vardhani. The raag-s, the raagini-s (Interviewer’s Note: in traditional nomenclature, raag-s were ascribed the masculine gender and raagini-s the feminine gender), the raag putra-s (as the word ‘putra’ meaning ‘son’ suggests, these refer to off-shoots aka progeny from pairings of raag-s and raagini-s) – we can adapt to anything. We also do not believe in small vs. big raag-s. Malasri for example – sa ga pa sa – just three notes. I have heard an elaboration of Malasri from my uncle without any repetition.

In the south, Amrithavarshini is regarded in a slightly lower standing. My uncle’s son has done an elaboration of it that impressed D. Balakrishna (son of saraswati veena exponent Sangita Kalanidhi Mysore V. Doreswamy Iyengar)- it is just how you look at it and how you approach it but if you look at it in a different way, ideas might open up.

Dhrupad is a very traditional art form. How much of evolution has already happened and how much more is allowed such that it does not detract from the lineage it comes from?

A lake will not survive unless new water gets into it either through streams or rain. Every generation will add something within the framework. Two mango trees of the same variety would still be slightly different. One might have grown in red soil and the other in black soil – but it would still be a mango. You have to know what makes it different and what keeps it the same. That difference is the nature of the person – the svabhaav. I might teach a phrase a certain way and the student might sing it differently. As long as the raagdaari is correct, as in it is within the framework, I will allow that. You look at that individual and their nature and you allow that to blossom. Everyone should have their individual identity. And the nurturing of that identity begins from the moment that person begins to learn. Every generation has a renewed sense of taste, smell etc., my father would remark. If you fix something without allowing change, it will die. Then, how much do we let it grow? That too has limits.

What are those limits?

Those limits are the rules of saadhaarani geetI. The sukshmuta (nuances) is the most important thing. If you listen to Pushpraj Koshti, for example, he is totally different from my father. But you cannot take away the fact that he is my father’s student. He is a very strong pillar of our parampara.

What is the biggest advantage of coming from a musical family vs someone who has no lineage?

Being in love the music, for the art of the music itself and not in a consumeristic manner – not playing for the audience. Seeing the notes, seeing the raag, just enjoying freely – just appreciating music for the sake of it – no stress, no tension, no performance pressures – just doing it for the beauty of it. The responsibility is completely on the Guru. The student is there just to learn and open his heart.

Sound editing by Sri. Madhu Apsara. Title Photo: Sri. Nick Haynes.

It is interesting you should say that. I frequently hear Hindustani musicians say prior to a concert that anything good is attributable to the Guru and anything bad is their own fault…..

It is just something they say. The student too can do good on his/her own.

It is perhaps just a clichéd phrase? Because I am not convinced.

I am not convinced either. I come from a tradition and I am not convinced about many things. Dhrupad and spirituality, for example.

How spiritual do you feel when playing dhrupad?

Do you say a halo around my head?

No, I don’t.

Then it is not spiritual. Spirituality is in the intention. In Maharashtra, there was this potter of legend called gora kumbhaar (meaning fair potter – as in fair in complexion) – one whose shadow if it fell on someone they would take a bath. He attained spirituality without ever entering a temple, without reading any scriptures.

“Spirituality in dhrupad, in my opinion, is just a selling point. We have sold it in the name of spirituality. How many actually enlightened people do you find in dhrupad?”

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on dhrupad and spirituality.

Just because you are singing a bhajan does not make it spiritual. What is your intention? When singing a bhajan, if you are thinking of money; when singing a concert, if you are thinking of pleasing the audience, the organizer or the next concert – that is not spirituality at all.

When you have truly surrendered yourself is when spirituality begins. And spirituality is not a piece of cake. I know people who are spiritually inclined whose lives have been pounded on just like dhaal in a mortar and pestle…. Spirituality is a very difficult path. You have to change the way you are as a person. You have to change the way your life is. How you see things. Are you changing everyday? What are you doing with those changes?

Dhrupad being spiritual is a clichéd statement that we have always opposed.

All Hindustani music, not just Dhrupad, has a very secular composition set.

That is because of the various languages – also the many kings who ruled in the North. Ibrahim Adil Shah II of Bijapur prepared the Kitab e Navraz- a compilation of all the dhrupad and khayal compositions of the time. Man Singh Tomar of Gwalior (one of the nine gems of Akbar’s court) wrote Manakutuhala – a 15th century treatise in Hindi describing music at that time. There are dhrupads written by Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb and Tansen. The rulers understood that to be a knowledgeable ruler, you had to know all the 36 arts – writing, painting, swordsmanship etc. When you live in a particular geographical area, you have to encourage the local arts to sustain it.

Earlier it was only about Shakti and Shiva – then it evolved into verses praising kings. There are verses with meanings like “your aura is like that of the sun or the sky; you are like God’s incarnation itself; everything – the elements, the oceans, the planets – is all under your protection; everybody is saluting your benevolence etc.” Dialogue between composer and the royal patron through music was routine and normal – many disagreements were ironed out that way. Then there was Sufi poetry. This was there for a long time.

Then we started giving it a very spiritual angle and forgot all the other rasa-s. In the olden times, there were the Nayaks, who were above the Gayaks – i.e. the Ustads and the Pandits. They had studied scriptures and had command over language and music and produced very deserving students. They were given the authority to compose – Nayak Bakshu wrote about sringara (love) rasa; one of our ancestors, Swami Haridas Dagur, wrote about bhakti (devotion) rasa. Someone wrote about the vir (bravery) rasa.

It appears that the cloak of spirituality came in after royal patronage ended. To perhaps find a way to be relevant or appear relevant in the public’s eye?

Two things happened. I will be very frank. Maybe people will not like what I have to say.

Yes, the spirituality aspect was brought in then. The royal patrons were replaced by patrons from companies, sponsors etc. – make them feel like the kings – so the music goes through and survives.

Making the music feel spiritual means you are making the music elitist. There is a big fear in being elitist. Coming from a tradition, we keep ‘rinsing’ our work through a colander to see the most refined stuff. When you do that, you get rid of the chaff. That might make the art fixed and the art will die.

Spirituality is not good for this. Music, in my opinion, is meant only for some people. I am not referring to people of a certain socio-economic group or education or any such things – I mean people who can open their hearts. In fact, I have seen the best audiences in the concerts I have played in villages under the SPIC MACAY auspices – right in Baratwada (rural Nagpur). They do not understand the intricacies in the music but you can see the appreciation in their eyes.

Listening without preconceived notions. Without expectations.

Exactly. We have tried to make it a very upper-class thing. Through SPIC MACAY, I have gone to municipal schools, tribal schools etc. and the genuine interest they portray and the questions they ask are unimaginable. You feel as though there is nothing to explain about dhrupad – that they already know it all.

Classical music could appear to have an aura associated with it based on where it is performed in – you need a sabha, a hall etc. And this is not just in Indian music – it applies to Western music too.

But that is not the case. Music comes from nature. It is best understood in nature. But we put it in ‘exclusive’ environments where people are just there to show off their silk kurtas and dhotis etc.

Despite dhrupad being a traditional, old art form, it seems to have definitely evolved. As you said, based on how the lyrics of the compositions have changed over time, by who it is patronized by and who it is performed to.

Even the aalaap has evolved. My father would say that his father sang something one way, that he would sing it a particular way and when my uncle sang it, it would be different again. That constant change is welcome and should be there in any art form. The ideology is traditional but it does not mean we do not change. Instead of a bamboo pen, we now use a ball point, right? But we still wear our kurta and pajama, saree etc.

Based on everything you have said, I get the impression that your father and uncle practiced music because they enjoyed it – that concerts and performances were only a side-effect.

If you have a bunch of roses in the garden, the rose that blooms the best will be noticed. You cannot hide it. You are lucky to do concerts. You cannot move away from the fact that your identity is because of the music. Your identity is because of the veena. How people know you is because of the music. We are lucky if we get concerts. But I know a lot of people who are amazing musicians but do not get many concerts – but you cannot take the musicianship out of them.

Could you mention some of them?

One is Yashwant Bua Joshi who was in Bombay – he is no more now and did not perform much but he was an amazing musician. People would involuntarily stand up and applaud intermittently at his concerts.

So what do you think about the MeToo scandal at the Dhrupad Sansthan? You were the first responder.

Actually, my wife was the first responder. It is a great loss. What happened to the students is very sad. What happened to the brothers too is regrettable. The empire they built was destroyed.

“In one light Dhrupad has taken a beating because they had popularized the art form. From another perspective, students who had given their lives for the cause of dhrupad could not do so. I think it was a power trip.”

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on the MeToo scandal at the Dhrupad Sansthan.

I doubt this was only in dhrupad though.

I have seen it happen a lot. Fortunately, our Ustads were free of these types of things. I spent so much time with them – the definition of Guru is that of a maarg darshak – someone who will show you the way. He cannot be anything more than that.

It is sad because they (the Gundechas) were students of my father and my uncle and they did not grasp what the Guru–sishya parampara was all about. We are all debating what it is, what it should not be. It is about practice of the art – not of control.

Even more than practice of the art, it is a lifestyle, right? Of morals, of character?

It is a lifestyle. But in today’s times, we cannot talk that much about morals etc. to students. We expect morals and respect with regard to music. Then, we just advice them to not behave badly with respect to society, to not disrespect people, to not throw your weight around. to try and be a good human being.

My wife and I both say these are the choices, and you decide what you want to do. It is one of the best systems to learn music but if you don’t understand how it works, it can be dangerous. It is quite demanding on the Gurus.

I think it is demanding on the students too.

These days students go to Guru-s who they think will give them more concerts or those who will have contacts. They do not go really to learn. The students are milking them and therefore, the Guru-s too milk them. They are all part of a system that just milks each other out. It is wrong but it happens all the time.

– Mohi Baha’ud-din Dagar on Guru-s and students ‘milking’ each other out.

Is it a desire for popularity?

Yes – it IS the popularity. Not quality.