G. Guru Prasanna

After having performed concerts for many years, the 24-year-old student approached the new Guru. “You should not touch the mridangam for five years. I have to teach you new fingering.” G. Guru Prasanna, whose musical trajectory has seen him play multiple instruments initially, before settling on the kanjira, says, “I had 100% faith in my teachers. I went to him as a plain white board on which he could write whatever he wanted. I literally did not touch the mridangam for five years.” The Guru here was C.P. Vyasa Vittala who then nurtured Guru Prasanna in the nuances of the Harishankar style of kanjira.

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu. Many thanks to Sri. G. Guru Prasanna for taking a lot of trouble to locate photos and audio for this piece.

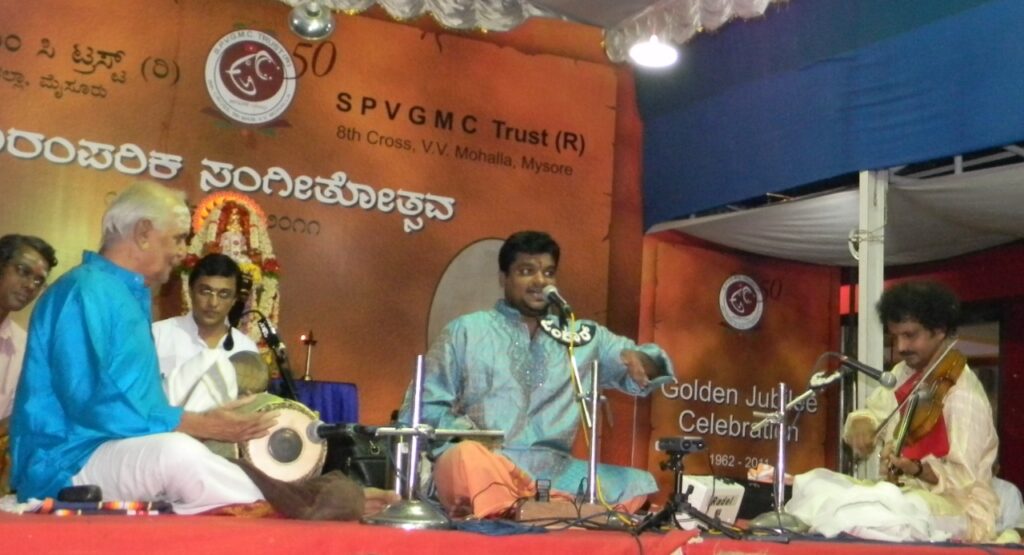

Guru has played with doyens of percussion and melody – a full list would run to multiple pages. Suffice it to say it includes the likes of Umayalpuram Sivaraman, Guru Karaikudi Mani, Trichy Sankaran, T.K. Murthy, Dr. M. Balamuralikrishna, Prof. T.R. Subramaniam, N. Ramani, T.N. Krishnan, T.N. Seshagopalan, K.S. Gopalakrishnan, A. Kanyakumari, Mysore Nagaraj, Mysore Dr. Manjunath, M.S. Sheela, Dr. Jayanthi Kumaresh, Sanjay Subrahmanyan, U. Shrinivas, Vijay Siva, Dr. S. Sowmya, Malladi Brothers, and many more.

Guru is a postgraduate in engineering from BITS Pilani and is employed fulltime as a Senior Engineering Manager in a multinational software company – he says that it is a dual passion for him – music and technology – and that he enjoys his job which he has been pursuing for twenty three years. “My concert experience and association with music is even longer though – more than thirty years,” he says.

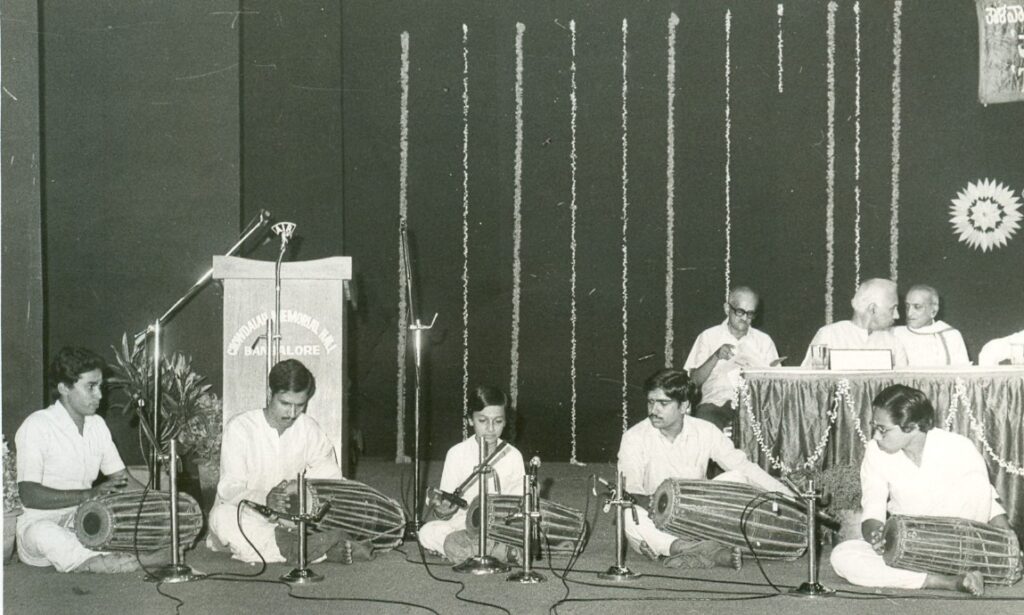

Though extended family members were involved in various arts such as theatre, movies and music, it was the temple opposite his house that drove Guru to music. “There were regular nadaswaram and tavil processions to the temple and my parents would feed me whilst walking behind them.” Noticing his interest in percussion, his parents enrolled him at the Ayyanar College of Music, a school for vocal, violin and mridangam (originally started by Mysore T. Chowdiah), under the Principalship of Anoor S. Ramakrishna. “As the first mridangam student of R. Sathya Kumar, I had excellent one-on-one attention from my Guru and I really enjoyed the learning process. I learned from him for 5 years.” When Guru got a three-year Karnataka State Scholarship beginning in 1987, Sathya Kumar suggested Guru Prasanna continue his training under Anoor Ananthakrishna Sharma, son of Anoor Ramakrishna. He continues his stewardship under Ananthakrishna Sharma.

Guru is probably rather unique in having played concerts in three instruments – mridangam, ghatam and kanjira. “I had an identity crisis for a while. When I was called for concerts, I would ask which instrument I was to play.” Practicalities can affect trajectories. Guru explains, “I was only 6 when I started at the Ayyanar College and they had only one small mridangam. As I grew older, younger children joined who needed that small mridangam. The bigger ones were still too large for me. So, my Guru suggested I play the ghatam.” Later, Ananthakrishna Sharma asked him to stop playing ghatam and, instead, take up the kanjira for concerts, since the fingers might otherwise get callused and affect mridangam playing.

A class with Ananthakrishna Sharma would frequently run to 4-5 hours. “Sir would play for an hour while I put talam. Then in the next hour, I would try to reproduce what he played. Following that, I would try to script the lesson. This process really expanded my memory and I realised I could absorb a significant amount at a time. Classes never had a specified duration – it was often I who would say I had to leave due to school or college etc.” As to how he could process, as a young student, hour-long sequences at a time, he says that the fact that he did think of it as onerous probably helped. “Had I been given shorter sequences, I might not have been able to absorb what my co-artistes do in concerts.” He says he builds a mental picture of the intonations (when it is a nadai – the subdivision of pulse within a talam – like tisram, catusram, kandam etc.), a note of where a sollu kattu (stacked rhythmic phrases) begins and the overall pattern as well. “It is like a gadbad ice cream (a famous multi-layered dessert in Mangalore that includes jelly, fruit and ice cream) – there are many layers. Whenever I forgot, I would ask and my Gurus would guide me then.” He explains that Ananthakrishna Sharma would teach even complicated aspects in an easily digestible manner. He would also play what he taught in concerts to show its practical applications. On Shivaratri, Ananthakrishna Sharma would engage his percussionist friends and selected students in an interesting exercise. There would be two bowls with chits – each person would take a chit from each bowl to find out who they were paired with and what talam and eduppu they were to play. They were given a half hour to prepare and then had a laya vinyasam for 45 minutes amongst everyone else present – an invigorating if slightly unnerving experience for all concerned.

Around 1993, Guru heard a laya vinyasam program at the Gokulashtami Series of the Odakattur Mutt in Bangalore, with Karaikudi Mani and G. Harishankar. Harishankar’s playing, in particular, made a deep impact. “Just thinking about that program gives me goosebumps even now.” Though he had played multiple instruments at concerts, that was the precise day he decided to specialize in the kanjira. For almost seven years after that, he played the kanjira but using mridangam fingering. On October 21, 2001, Guru played the kanjira at a packed auditorium featuring vocalist P. Unnikrishnan with H.K. Venkatram on the violin and V. Praveen on the mridangam. “I was just found wanting on that stage. I could not keep up with what Praveen Sir played that day.” He returned highly disturbed and spoke to his Guru about the incident. Ananthakrishna Sharma put him in touch with C.P. Vyasa Vittala, a student of G. Harishankar. So, at the age of 24, Guru began formal kanjira training. “It was a most difficult phase. I had to literally unlearn everything and start all over again.” A student of any field will relate to how relearning is harder than learning from scratch. The challenge began with the simple ‘ta di gi Na tom’. He practiced for hours and did not get the correct tone. When he contacted Vyasa Vittala, he was asked to practice it for two more months – it still did not come. It was only then that Vyasa Vittala said, “You need to stress in this particular place.” The very next minute, Guru got the perfect sound. When he asked why he had not been told this earlier, he was narrated the analogy of how only a hungry man would know the value of food. “I wanted to see how hungry you are,” said Vyasa Vittala. Vyasa Vittala, Guru says, would watch out for his student and how he was practicing. He learned phrases specific to the instrument, what to play, when and how and, more importantly, what not to play as well. “While I have learnt the science and logic behind the percussive art and internalizing those from Ananthakrishna Sharma Sir, I have learnt the art of practicing and presenting all of the complicated structures from Vyasa Vittala Sir”.

Fellow kanjira exponent and childhood friend BS Purushotham says that Guru is one of the few who attends several concerts. Guru would discuss aspects of what he heard with his Gurus and ask questions. There were many times when he would be told that it would be some time before he understood certain aspects. “I realised that there were many disparate dots being formed. My suggestion to students is to surrender to the Guru completely – eventually, all the dots will join and a complete picture will emerge. I follow this with my technological career too – there are things I don’t understand at a particular point in time – but eventually, I will comprehend it.” He says the initial progress might appear very slow but that there would be exponential growth if one perseveres, rather than yo-yo amongst Guru-s.

Since traditional kanjiras are becoming increasingly difficult to procure, the modern fiberglass kanjiras are being used these days, particularly among beginners. Guru feels that while these instruments do offer more convenience in being easy to maintain and, therefore, to travel with, use for rehearsals, fusion concerts etc., nothing can match the tonal quality of the traditionally made kanjira for a Carnatic concert. He says for every advantage, there often is a disadvantage. He continues to use the traditional quarter anna coins for jingles in the kanjira – his grandfather had collected some and Guru regularly peruses stores that might carry authentic supplies for his instruments. He says that, besides the skin, even getting good jackfruit wood frames for the kanjira is more difficult now than before – like the ghatam, barely 5% or so would be of concert quality. “Vyasa Vittala Sir has taught me how to maintain the instrument and to take care of it in any situation. He has also handpicked a few instruments for me. They are worth gold!”

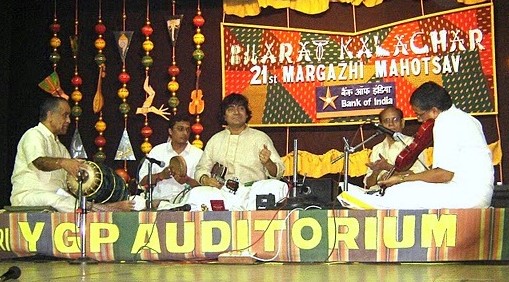

Many concerts are memorable for him. Since his first for the Late U. Shrinivas in 2006 in Bharat Kalachar with Trichy Sankaran on the mridangam, he was a fixture at Shrinivas’ concert in that sabha. Another is with the Mysore Brothers where he played the kanjira with Giridhar Udupa on ghatam sans any mridangam since the mridangist, Bangalore Arjun Kumar, had been taken ill suddenly. One with Yogesh Samsi on tabla where Guru played entirely Hindustani bhOls on the kanjira was a different experience.

Guru Prasanna accompanied Vinay Sharva in 2009 for an exposition of a rAgam tAnam pallavi set to the 128 beat Simhanandana tALam – “I wondered – should I remember the angas (components of the talam, like lagu, drutam, anudrutam, plutam etc.), what went into each part or the talam or the pallavi structure? If I miss once, I will have to circle for 128 beats to get to samam.” Here Ananthakrishna Sharma told him to think of it as 4 cycles of 32 rather than 1 cycle of 128. After every 32, the anga changed and 32 was merely two cycles of vilamba (slow) Adi talam. “Thinking of it that way made it not just achievable but also something one could improvise with. It changed my entire view of rhythm itself.” He had been told from the beginning that he was to play for the melody and not the talam. This was reinforced when Ananthakrishna Sharma would ask percussion students to play for his vocal students.

Vocalist Saketharaman says, “Guru Prasanna’s pattu gnanam is amazing, especially of Purandaradasar Devarnamas. Once, I commenced the concert with Vandisuvudadiyalli in Nattai. The mridangam vidwan had to retune his mridangam during the charanam. Guru Prasanna exactly anticipated Ume Nandhana, which is 1 swaram atheetha eduppu (before samam). These are the moments that lift a concert and make it vibrant.”

Guru says, “For me, Sivaraman Sir and Mani Sir are Gods.” He first played with Umayalpuram Sivaraman at Odakkatur Math in 2007 for Saketharaman with M.A. Sundareswaran on violin. He also recollects his maiden concert with Guru Karaikudi Mani – at Krishna Gana Sabha for TV Sankaranarayanan with V.V. Ravi on violin. “Mani Sir asked me to come a day earlier and see him but I was committed to Srikantan Sir in Vishakapatnam the previous day. He instead asked me to come a half hour earlier on the day of the concert to the sabha.” He continues, “Mani Sir told me – you have come to play, not just to sit. Play without hesitation or fear. I want to see you get as much applause as I do.”

Playing with stalwart mridangists can require a slightly different tack. “As younger artistes, we cannot hope to have the rapport that a Harishankar Sir, a Nagarajan Sir or a Ramachar Sir might have had with senior artistes like Sivaraman Sir, Mani Sir, Murthy Sir, Yella Venkateswara Rao Sir, A.V. Anand Sir or Kamalakar Rao Sir. One will definitely be tentative initially. One wonders what, how and where to play. They have to first develop a trust in me, and the onus to achieve that is on me as the younger artiste. When they look at me, I have to interpret it – is it an approving look or not? Was it correct for me to have interjected there? It takes a while.” So, Guru prefers to wait and watch, citing Sivaraman here, “He has adviced that even if one is itching to play something, one should actually patiently wait until the correct moment.” He juxtaposes this with a particular sequence Sivaraman would play in every concert. “We would wait for it in eager anticipation. We knew it would definitely come. But where he would play it would be the mystery – when it came, it would be so appropriate, so perfect, that we will know then that there could have been no better juncture to play it at!”

Guru feels that the senior most stalwarts are very aware of how their music, and the overall sound, reaches the audience and that might be a key reason why they are frequently particular about where their co-percussionists can interject. Yet another factor is the time required to settle to the entire stage dynamic – their own comfort level, all the other artistes and their individual dynamics with them, the state of amplification and balance etc. Once one has proven efficacy with the senior most artistes, a confidence has already been established making it easier with others.

“As the younger artiste, I have to understand and interpret everything in a split second – this comes from extensive listening to the music of that mridangist both on and off stage and using that knowledge appropriately on stage.” He adds that he has to be aware of the intricacies and compositions of the different schools of mridangam – the only way to “lock in and gel” as he calls it. Purushotham notes Guru’s quality of adapting to the various styles of mridangam playing he encounters. Guru adds that this does not apply to senior artistes alone. “If a group of musicians have toured together and I am joining in at a later stage, I have to be aware that they have a rapport already, listen to what they have done as a group, interpret things that might have happened off stage, comprehend the music and play accordingly to embellish.”

Mridangist Bangalore Arjun Kumar refers to Guru’s playing for eduppu-s: “His approach is very fluid – he can weave a korvai using any nadai with appropriate sollu-s to land perfectly on the eduppu – his sharp intellect is very apparent to me here. His phrases reflect very solid sollu kattu-s played with ease and unique for the kanjira. His fingering technique is highly evolved.”

Guru says one cannot prepare specifically for a particular concert but must keep listening with an awareness of how each artiste is playing. He likens it to a quiver filled arrows and knowing what arrow to pull out on what occasion. As a percussionist, there is a side of him that immediately tunes in to the percussion aspect of any music he listens to, but he insists that the melody is an integral part of it. He mentions this contextually using a Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer (SSI) recording. In this concert circa 1960s, SSI is accompanied by Lalgudi G Jayaraman and Umayalpuram Sivaraman. The concert begins with suryamUrte in dhruva tALam, followed by dEva dEva kalayAmi and moves on to ambA kAmAkshi in bhairavi. Besides observing how Sivaraman played for suryamUrte and for particular sangatis, Guru noticed how it is not until the neraval in ambA kAmAkshi that Sivaraman comes to his own, transforming the entire concert. The concert continues in that groove for a while after which SSI begins kshINamai in mukhAri – where he observes further shades of Sivaraman. “I have listened to this concert several times and in all moods and the end result is always the same – a feeling of elation – there is such freshness every time and I am raring to go to practice.”

Violinist Mysore Dr. Manjunath remarks, “Guru Prasanna is outstanding at finding the intellectual continuation of whatever is played by the violinist or the mridangist – it is a technically perfect and intellectually accurate replay spiced with beauty. Even those who might prefer a ghatam or a morsing would change their mind if it is Guru Prasanna.” As if echoing that, Saketharaman says, “I usually ask for Guru Prasanna’s availability for a concert even before I fix up the mridangam vidwan.”

In concerts or recordings, it is often difficult for a ghatam, kanjira or morsing artiste to hear their instrument in isolation except during the tani. Guru explains that what he observes is that it is not how long the second percussionist plays but where and how. He mentions other anecdotes. “There are so many combinations I have heard. Some stand out.” He refers to one of T.N. Seshagopalan, Mysore Nagaraj, Palghat Raghu and T.H. Vinayakram – a collection of brains, Guru says. “Vinayakram Sir was hardly noticed. However, whenever he did play, it was to thunderous applause.” Another occasion he remembers is in 1998 – the team of Neyveli Santhanagopalan, Mysore Manjunath, Umayalpuram Sivaraman and G. Harishankar. The audience was itching for some excitement. “At one juncture, Harishankar Sir played just one tarikitadhim – immediately, Sivaraman Sir acknowledged Harishankar Sir and the whole complexion of the concert changed right then.” Another memory is of V. Suresh on ghatam along with Srimushnam Raja Rao on mridangam – “the way Suresh Sir played the double ghumki-s was out of the world.” At a concert of O.S. Thiagarajan, dEvi brOva samayamide was sung sedately with Sivaraman too keeping a low profile. Harishankar, he says, literally sat with his hands folded for the entire kriti. Guru explains, “That silence meant so much. It is not about being heard – we have to think of the meaning behind those silences. It is about when to play and what and when not to play and how. Sometimes you are not playing because you are aware you are not playing.” He admits this might have frustrated him in his younger days but that, now, he keeps the listener in mind and plays only if he believes it will actually add value to the overall music. “My favourite words are practice, patience and perseverance. Patience is a very key element. We have to get into the groove of the music that is happening and play along with it. We cannot go tangentially. The output really matters.”