Kala Ramnath

Simple and unassuming, Kala Ramnath exudes a gentle, innocent vulnerability that betrays the titan that she is in Hindustani music. One of the youngest recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar, she has put her distinctive stamp on Hindustani violin, made it a force to reckon with, and put it on the world map. She has been hailed as one of the world’s 50 best violinists, was the first Indian to be featured in the violin Bible ‘The Strad’, and her album ‘Kala’ was selected as one of UK-based Songlines magazine’s 50 best recordings. The latest accolade? The New York Press recently inducted her into the list of the 100 Most Influential Asians. It is, indeed, a pity that despite her world renown, she is little known in South India, this despite being a South Indian raised in Chennai.

To begin with, the violin is uncommon in Hindustani music. Kala, however, has blazed a trail all her own here, after V.G. Jog and Kala’s paternal aunt, Padma Bhushan N. Rajam, got it recognised in the firmament. Kala reinvented the handling of the instrument itself which has resulted in a uniquely refined sound, much lauded by critics the world over, regardless of genre. A practitioner of the gayaki ang, she painstakingly developed the techniques to convey even the most minute microtonal nuances as clearly as vocal in her instrument – earning her playing the epithet ‘the singing violin’.

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu. Sincere thanks to Sri. Swami Venkataramani for doing a photo shoot on location, at short notice, specifically for this piece, under challenging circumstances. Many thanks to Ms. Kala Ramnath.

Quiet and soft-spoken, she is nevertheless very articulate with conviction in her thoughts. She firmly feels, for example, that musicians should not offer their art for free, pandemic notwithstanding. “If you feel you should be seen online, then teach, offer advice, help others,” she says. “How can performing at home, without accompanists, even be called a concert? That is merely your personal practice you are putting up. If you want to put up a concert, then get a studio, get accompanists, do a proper, professional recording, put it up on the web and charge for it.”

Kala’s life with music began with her grandfather, Trippunitura A. Narayana Iyer, putting a violin in her hands on Vijayadashami Day in 1969 when she was two. Narayana Iyer mentored Kala personally throughout the day, preparing exercises for her. “Thatha would ask me to practice each sequence 100 times. If I faltered or made a mistake, even in the 99th time, I would have to start from 0 all over again.” Intense as it was, Kala says it taught her to not lose focus and concentration. At the end of each sequence of a 100, her grandfather would let her choose one colour from a bowl of multi-coloured candied fennel seeds – her treat for having got that right. Was this not incredibly tough, as a child? “I was so fond of thatha that I would do anything he asked for. If he said the sun rose from the west, it rose from the west for me. He would wake me up, tell me stories, helped me with my homework – he was everything for me.” She gets emotional as she recollects his affection – his picking her up from school, buying her candy, and sometimes getting her semia payasam, a favourite. The entire household had to watch their activities during her practice which was not to be disturbed by anything else – be it the pressure cooker or the pump pushing water to the overhead tank.

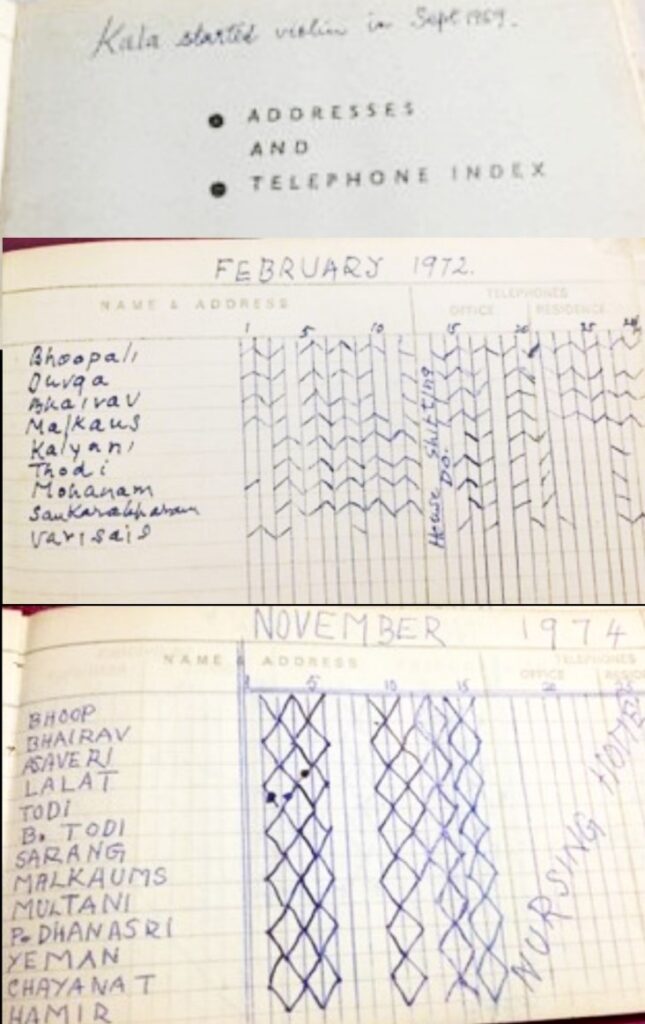

It was a childhood unlike most her age. “I have never gone on excursions or had friends come home or gone to friends’ houses. No reading Perry Masons or Enid Blytons, nothing.” All the time except for school and homework was spent practicing the violin. Four hours was routine on working days with six on other days. “I got one day off every year – on Saraswati puja,” she says, “Violin practice was a way of life – like having meals, taking a shower – the only exceptions were if I was badly sick with chicken pox, measles etc.” Narayana Iyer maintained a systematic diary of her practice – looking at it, one can see how many rAg-s and which rAg-s she was practicing at the most tender of ages.

Kala was a quick picker upper who mastered her grandfather’s exercises instantly, challenging him to come up with new ones in quick succession. She mentions that there were days when he would wake her up at 2 or 3 am (even as her grandmother protested that ‘the poor child’ was not even allowed to get proper rest) having got an idea for a new ‘varisai’ (exercise) that he would want her to play right away. For several years, he maintained a diary which noted down what she had played each day, how many times etc., methodically. He taught her elements of both Carnatic and Hindustani simultaneously, including the initial exercises in mAyA mALava gauLai and bilAval, respectively. She recollects some of the varNam-s and kriti-s in Carnatic that she learned including mInAksi mEmudham dEhi, brova bAramA, Sri bAlasubramanya etc. When Kala was 7, her thatha told her to focus completely on Hindustani, perhaps enabling differentiation from at least four cousins who had taken up Carnatic.

Grandfather and granddaughter would together listen to, and analyse, all the Hindustani programs that came on the radio and recordings. She attended all Hindustani programs in Chennai with her grandfather getting her to play before many of these artistes. Kala remembers playing rAg miyAn ki malhAr at age 7 before V.G. Jog. A.T. Kanan and Malabika Kanan taught her a composition in Bhairav. When Bharat Ratna Bhimsen Joshi came to perform at The Madras Music Academy in 1980, she played before him. He asked her what she was learning and even sang that rAg for her! “Thatha tried to give me whatever exposure he could to the people in the field,” says Kala.

A necessary part of practice for Hindustani music, her grandfather played the tabla for her daily practice and once a week, a professional tabla player would come home, at a king’s ransom, for her to get that experience too. During summer breaks, Kala would visit her aunt in Banares where she could practice daily with professional tabla artistes.

Kala gave her first public performance at age 12 in Bombay, a duet with Rajam’s daughter, Sangeeta, arranged by Rajam and presented by Pandit Jasraj. Kala took the audience by storm that day, everyone asking who this hitherto unknown quantity was. Pandit Jasraj took a personal interest in Kala then onwards, mentoring her as needed, much before she joined his tutelage.

A turning point, which she has mentioned in earlier interviews, occurred when tabla exponent Ustad Zakir Hussain visited the family in 1982 to convey his condolences on Kala’s father’s passing. When she played for him (on her grandfather’s request), he said that she sounded like her aunt, and why would anyone want to listen to an imitation? “That stuck with me. I was too young to decide what to do about it then, but that was another reason I eventually went to Pandit Jasraj.”

She performed only rarely after that initial performance though, her grandfather looking at these opportunities purely as encouragement for Kala to continue practicing with more zeal. She did a BA in History from Stella Maris College and also a Bachelors and Masters in Music subsequently.

Kala then relocated to Bombay. She received the A Grade from AIR Lucknow (she was one of the youngest to get it) in a double-blind audition where neither the judges nor the candidates could see each other. She played rAg natbhairav and was then asked by the judges to present a full synopsis of rAg Shree in 3 minutes – AlAp, tAn and composition and not in the most common teen tAL. She recollects her grandfather’s tears of joy and pride at this accolade when he said, “you have given me the greatest happiness a Guru can get.” Until then, he had never told Kala where she stood or how good she was. As a result, she grew up unaware of her prowess, perhaps the keystone to her being grounded and without airs to the present day. One should note Narayana Iyer’s vision and confidence here in unhesitatingly molding Kala as a solo performer only, with no notion of ever accompanying – most remarkable. Narayana Iyer’s own familiarity with Hindustani music came from having lived and worked in Bombay, and playing with Vinayak Rao Patwardhan, Omkarnath Thakur etc. He had learned Carnatic violin from his own father.

Once in Bombay, she became a prime disciple of Pandit Jasraj. “Jasraj-ji would conduct an annual camp – for some 10-12 students who would live on site for the 15-day duration. There were two sessions of daily classes – from 10 am to 2 pm and from 6 pm to 10 pm. All we students had to do was to show up for class and practice the rest of the time – food, laundry, everything was taken care of.” Kala’s home in Bombay was walking distance from where Pandit Jasraj would conduct his day-to-day classes. It was a group class where most would sing and the students would repeat. Kala too would usually sing and then come back home and play whatever she learned on the violin. This was not new to her – her grandfather too had always taught her only via vocal. She also learned a lot from Pandit Jasraj’s recordings. She remarks that most violinists who do not reflect the sahitya in their playing probably learned from instrumentalists who themselves did not know the placement of the syllables of the lyrics. “Pandit Jasraj paid a lot of attention to the sahitya – uncommon in Hindustani music. He did research on haveli sangeet to find the original lyrics. He also brought in Sanskrit into Hindustani music,” Kala says, about the recently deceased Pandit Jasraj.

In her decade long period of active learning from Pandit Jasraj, she acquired much of her knowledge from accompanying him at live concerts, she says. She would go ahead of time, set up the stage, the microphones and ensuring everything was ready for him. Kala’s own understanding of the placement of the individual notes became much more embedded at this time. She gives an example – “Though both have the komal Re, the Re of Bhairav is higher than the Re of Shree. Jasraj-ji looked at each rAg as an individual entity with a personality of its own – and if that personality was not awakened, he said he would be able to touch his audience.” This awareness, at a minute level, of the microtones, was rapidly fine-tuned in Kala. “After a concert, I would ask him about the relative positions of a note, and then would look for that everywhere in my playing and my listening. Jasraj-ji also taught me how to handle myself as an artiste, from having a dress code to presenting myself, to what to present and how to interact with the audience.” He called her a computer, for her very sharp memory and her instant absorption. Her sense of sruti is acute – she can sing or play any sruti sans a tanpura for reference. She can, thus, also tune acoustic tanpura-s very sensitively.

At Rashtrapati Bhavan.

It was her desire to reproduce even the tiniest nuance of Pandit Jasraj’s vocal music on her violin that led Kala to undertake a massive and thorough reworking of every aspect of her instrument and its playing. She reworked her fingering techniques (the left hand for right-handed individuals) extensively. Knowing that the moving of fingers from string to string, and within various points on the same string takes time, she rethought the fingering completely – optimising and minimising movement as needed. This was crucial in her being able to bring out the vocal subtleties on the violin with clarity.

She explains using a few examples. “The upper Sa is normally with the pointing finger which needs to slide up to reach that note – this can reduce the maximum speed that can be attained. Instead, one can play it using the 2nd and 3rd finger on the other strings – this can optimize the efficiency and the sound. Sometimes, one needs to play the ‘N’ immediately after the ‘S’ but one should not hear the lifting of the finger – so I worked on that – lifting the finger so gently but such that the ‘N’ is still heard distinctly.” She explains how she would play ‘PMMG’ – playing the two ‘M’s with two different fingers, to ensure that the two ‘M’s are heard very distinctly and clearly. She also explains ‘PDNS’ (as in Carnatic kalyANi) that would normally be played fully with the index finger but can actually be played with multiple fingers that would make it easier to execute. She says that, generally speaking, Carnatic musicians tend to use two fingers predominantly though four are available – the key, is to know when to play with which technique and how to still sound as smooth as while using just the one finger.

When asked if she used to play the preponderant way herself earlier, she says that what she does recollect is her grandfather telling her to not use the index finger too much and to employ the middle finger more often too – “I did not understand why he said that then, but now I do.”

A hallmark of her grandfather’s training, which has served her very well throughout, is the use of the entirety of the bow. The is also seen in the playing of her uncle, Sangita Kalanidhi T.N. Krishnan, and Rajam, both trained by Narayana Iyer. Narayana Iyer’s advanced teaching pedagogy has to be mentioned here – right from asking Kala to focus on a rAg a week where she would have to play all the compositions she knew in that rAg, to identifying pairs of ‘opposite’ rAg-s to practice – she mentions Ahir bhairav (similar to the Carnatic cakravAkaM)and Hindustani tODi (similar to the Carnatic SubhapantuvarALi) as one example – practicing these rAg-s which had notes close together and further away, ensured nimbleness and dexterity in the fingers allowing for all intermediately distanced notes to also be played effortlessly.

Her recreation of the sound did not stop there. Most violin solos are played at pitches of 3 or 3.5, but Kala felt that it was not very soothing to listen to the instrument at that pitch after a while. Perhaps the contrast was amplified with her playing for Pandit Jasraj at 1.5. She decided on a pitch of 2 for her solos. However, she did not stop there – she was looking for a rounder sound, more mellow yet sonorous. She experimented with banjo and mandolin strings, but was not satisfied. Then, a brainwave struck. She used strings of the ¾ viola, which is, more or less, the size of a full violin, and found that this was an excellent solution, given the more bass sound of a viola. She says that if she had not had to play in Pandit Jasraj’s style, she probably would not have worked on changing all these various aspects of her playing style.

She picks up ideas everywhere. When teaching at country music camps in the US, for example, she noticed how the violinists there had an interesting way of using the bow in a staccato manner (very unlike that of jOd/tAnam) such that rhythm was brought in just with the violin – with the many violins there, some would play it in the normal fashion while others would bring in the rhythm element – like an acapella with violins alone. She made a note of some of these techniques.

Colombo, Sri Lanka. Early 2020.

Besides teaching engagements at august conservatories, she teaches many children vocal and violin individually, most of whom began from the basics when they were very young. Some of her vocal students are at advanced stages of learning. “Some of my violin students will be concert grade in 2-3 years”, she says. “What take 5 years to achieve in vocal would take 14 years in violin.” She divides her time between India and the USA and has students in both countries and in Europe as well. She recently organised an online workshop for her students asking them to explore families of rAg-s – the kalyAN-s, the kAmOd-s, the kEdAr-s, the hamIr-s, for example, to get them to understand the interrelationship, similarities and differences between the rAg-s.

On what it takes to be a successful performer and the not necessarily linear relationship between practice and success, she mentions several aspects. Firstly, while one would, and should, be reminiscent of one’s Guru-s in one’s music, one should not be a blind copy – as Zakir Hussain told her all those years ago, why would one want to listen to an imitation? Pandit Jasraj made the same point in a different way – one’s biological children might be like one initially but, after a point, that child’s individuality will come through, though the physical resemblance might continue – and so it should be with the music – one’s unique self should present itself in the music but with the undertone of the provenance. Secondly, one should do one’s riyAz not merely quantitatively, but qualitatively too – with careful, directed thought – just blind practice will not get one far. Thirdly, she says it makes a real difference whether someone is in the music because they want to be vs. because they have to be or are coerced to be in – “If you really want to do it, you will automatically put in all the necessary effort. If you are skilled and unique enough, you will definitely be noticed.” She states the importance of realistic expectations here. “This is a niche field. A classical musician cannot expect pop idol status. To expect that kind of adulation or following is just unrealistic.” She additionally stresses the importance of honouring a commitment, recalling Pandit Jasraj. “Once I was due to perform in Hyderabad and got a high fever. Jasraj-ji‘s wife suggested that I should not play. But he said that God would give me the strength at that time. I performed and it was a very successful concert. He was like that himself. If he had given a commitment, he would make it – nothing could stop him. We had once gone to Namibia for a concert organised by the Indian government. Due to some confusion and miscommunication, we were given barely fifteen minutes to perform. Jasraj-ji told the audience that whoever was interested could come to where he was staying and he would perform for them there. Several came and we performed a full-length concert. That was when he felt he had fulfilled his commitment.”

Hindustani music ascribes rAg-s to be rendered at certain time windows of the day or night. Several rAg-s, particularly those sung late at night or very early in the morning, do not get presented, as a result. Asked if it might be time to let go of these confines, so as to bring forth these rAg-s to audiences, Kala says that it probably should be done. “It is, however, difficult to let go of these strictures that have been in place for so long – it is somewhat of a mental battle.” She also wishes that time limits and noise level covenants allow for exceptions for classical music.

Kala approaches her many collaborative musical engagements very seriously- not for her merely identifying a convenient rAg and the co-artistes joining in as needed. “Just getting together and playing on the spot is a jam session – not a collaboration,” she explains. For one with the Danish Symphony and Jazz Orchestras, she flew into Denmark four times over two years, spending a week on each occasion, with much communication in between as well. For another with the London Symphony Orchestra, the composer/conductor visited India, stayed awhile, brainstormed and recorded her music. After returning to London, they engaged in active communication before presenting the joint effort a year or so later to rave reviews. She has just released a new album titled ‘Rang’, a collaboration with Bickram Ghosh, made entirely during the pandemic, with each artiste recording their respective parts at their homes and Ghosh putting it together.

At present, she is introspecting deeply into the music. “I am looking at different rAg-s, delving into challenging compositions, and looking at ways to approach the rAg, how to elaborate on it and what I can create differently there. Bringing out more beauty in the rAg is what excites me now. If there are three or four rAg-s very close to each other, I try analyzing the one from the perspective of the other – keeping the other rAg in mind whilst staying in this rAg. I am exploring these aspects more minutely and deeply.”

Kala Ramnath says, in conclusion, “I wish to avoid the rat race, just play good music for as long as I can and live a peaceful life. I do not seek recognition. If it comes my way, well and good.”

Listen to Kala Ramnath’s podcast from the Quarantunes series too.

Very nicely written, Vidya. Thanks for giving me this rare opportunity. Doing a photoshoot while listening to Kala play the violin was a mesmerizing experience!