L. Ramakrishnan

This artiste was extremely clear that music was what he wanted to pursue and would have discontinued his studies after 12th Grade, had his Guru not persuaded him to complete his degree. “I had stubbornly refused to listen to my parents,” says L. Ramakrishnan who can be seen accompanying practically every known name in Carnatic music now. His Guru is Sangita Kalanidhi A. Kanyakumari. “I am so glad now, though, that my parents, and my Guru, insisted that I graduate,” says Ramakrishnan.

Such is the pull of the solo act, that many accompanying violinists, often very skilled ones too, frequently forget that what they are doing is accompanying. To play in a supportive manner so as to embellish and enhance the other artistes requires a very different demeanour and thought process from playing solo. It necessitates tempering one’s own urges, concentrating on the other artistes and going with their flow, not one’s own. Ramakrishnan is one of the rare few who has understood this role superlatively and rises to the occasion. When one is an erudite musician oneself, putting a lid on one’s creativity is no easy task. Ramakrishnan observes whichever artiste he is playing for, like a hawk, and anticipates and follows him/her carefully. Sangita Kalanidhi Dr. S Sowmya says, “His knowledge of vocal music (he is an excellent singer himself) and his quest for learning and asking questions, are most creditable. He plays in strict proportion. One has to practically beg him to play more.” Ramakrishnan Murthy adds “He is the ideal partner to have on stage – he will bring out the salient points of what has been sung and spur you on as well.” He has an uncanny knack of knowing how much to play and where exactly to play it, avoiding the common irritation of many violinists who will replay what their co-artistes rendered but a few notes behind – it is uncomfortably dissonant but so common that rasikA-s are practically desensitized. It is no wonder that the list of artistes he has accompanied ranges from Sangita Kalanidhi-s T.K.Govinda Rao, T.V. Sankaranarayanan, T.V. Gopalakrishnan, Nedunuri Krishnamurthy, Bombay Sisters, R.Vedavalli, Sudha Ragunathan and Dr. S. Sowmya to the Hyderabad Brothers, N. Vijay Siva, Bombay Jayashri, Ranjani & Gayatri, and T.M. Krishna to most of the known younger artistes of today.

A version of this piece appeared in The Hindu. Sri. L. Ramakrishnan’s photograph in the The Hindu is courtesy Sri. Ramanathan Iyer. Many thanks to Sri. Ramakrishnan for digging through archives in Bombay and Madras to locate audio, video and photographs for this page.

Ramakrishnan’s maternal grandmother had learned music, and her brother, known as ‘Town’ Balu, was reportedly GN Balasubramaniam’s first student and a Graded artiste of AIR. Music. The GNB bANi, in particular, thus, filtered through to the family. Ramakrishnan’s first three years were in Kuwait under his mother’s tutelage where he learned the harmonium and performed bhajans at local functions. Upon returning to Mumbai, his grandmother began teaching the child. She soon spoke to Dr. Sulochana Rajendran, then Director of the famed Shanmukhananda Vidyalaya, who mentored him. Ramakrishnan, hearing a friend play the violin, felt the urge to take up that instrument. “I really like vocal and it would be my first preference, frankly,” he says. “However, I did not like the sound of my own voice. Besides, I had frequent throat issues due to tonsil problems.”

He began the seven-year violin course in 1993 under Visalam Vageeshwar. Ramakrishnan explains that the initial period of violin training is the hardest. “It takes about two years for us to actually like the sound we are producing. One is often tempted to quit.” He stuck with it, successfully getting the Shanmukha Mani title in 2001. In 1996, a visiting aunt, recognizing his potential, suggested he get some training in Chennai. The family thus approached A. Kanyakumari who took him on immediately. Ramakrishnan went to Chennai for every December break, and during the summers too, and received intensive training.

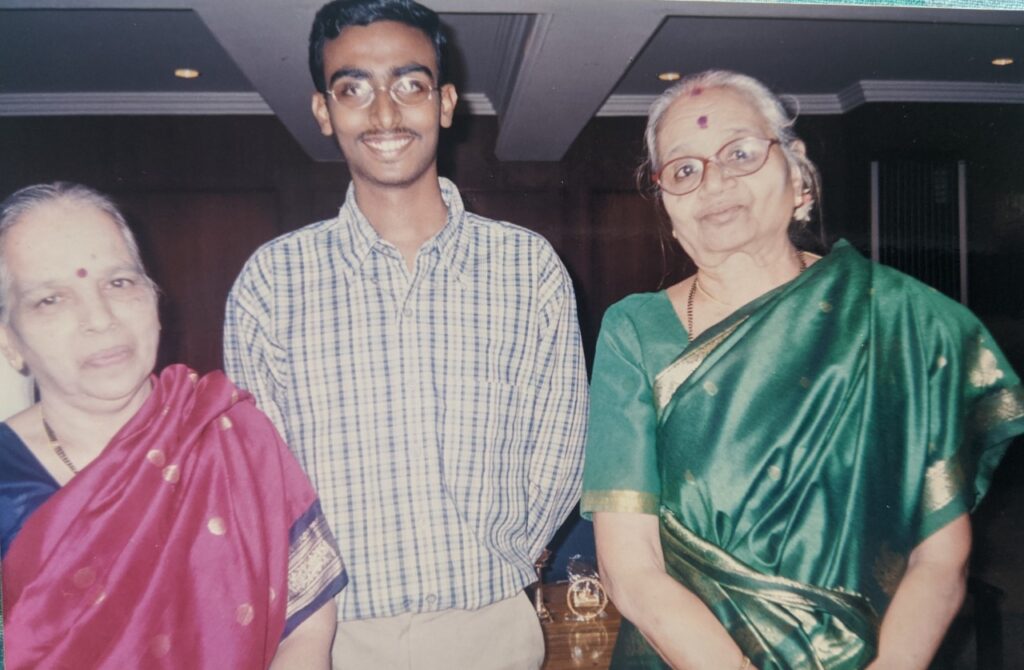

November 17, 1996. Sri. Kumar on mridangam.

The relevance of institutionalized learning of art forms is frequently questioned since not too many performers emerge therefrom. Ramakrishnan explains though, that he gained a lot from his training at Shanmukhananda notwithstanding the fixed syllabus necessitated by such a system. “To listen to several other students play in a formal classroom situation is invaluable. We imperceptibly pick up so much on what to avoid and what to imbibe right there,” he says. As his mother was doing her Diploma in music at the same time, he would often sit in the senior class with her. There he picked up navAvarNam-s and navagraha kriti-s etc. from Kalyani Sharma, an expert. “At that time, I was not really motivated to learn them. However, it was all assimilated. Much later, I understood the merits of these songs and how well Kalyani mami had taught them. It made me realise that only when the time comes can one appreciate some aspects.”

Ramakrishnan, however, says that the training at Shanmukhananda required augmentation to perform at the highest levels. His playing was technically correct but “…just as one cannot be good in a language with good grammar alone, Kanyakumari teacher made me realise how much more there was to good music.” She elaborated on how to accompany and where playing might actually hinder the overall experience of the concert. “I found I would overdo or underdo the gamakam-s. She helped me fix that. She also taught me how to bring in ‘sAhitya Suddham’ in playing, how to stress syllables and which ones to.” He explains that students who go to Kanyakumari, regardless of where they begin from, experience exponential growth in their skills. “Such is her sincerity. She teaches patiently according to each student’s needs. She never looks at time. On many occasions, I have been there until the wee hours of the morning.”

Photo courtesy: Sri. R. Ragu, The Hindu.

A key aspect for an accompanying artiste’s sustained success in the performance circuit is learning on the fly. Accompanists are frequently confronted with songs, calculations, and even rAgam-s, they are not familiar with. They have to assimilate this instantaneously and respond barely seconds later. This is why, Ramakrishnan says, how one has approached the music is critical. It is important to learn the thought process behind various aspects of the music vs. take the easy way out. Rather than ‘learn’ a few sequences of neraval, the science behind it should be taught, for example. Exactly how an instrumentalist plays the instrument will also vary. Kanyakumari, he explains, never taught by playing the violin – she would sing. The students would figure out how exactly to play it with Kanyakumari stepping in only if needed. Ramakrishnan says that if one of his own students is stuck, for example, he suggests up to three ways to play a phrase. “If none work, I ask them to find one that works for them. It is important they learn the skill of themselves figuring out how to respond – it must be inculcated.” In 2001, at the age of 17, Ramakrishnan performed at his first concert in Chennai, accompanying Vidya Kalyanaraman.

When instrumentalists change teachers, differences in fingering styles can become a problem. Ramakrishnan says it is a very real issue that he, fortunately, did not have to face. “I didn’t have to change anything. The fingering taught by Visalam teacher at Shanmukhananda is what I still use today. Her dedication was incomparable. In all those seven years, she did not take even a single day off.”

Ramakrishnan joined Bombay Balamani for a while. “She would give us full, very detailed, notation for everything she taught,” he says. “Yet, if we played or sung it slightly differently, she would let us do so.” He learned a lot of kriti-s from her and since the class had vocalists, violinists and flautists, he learned of the limitations and scope of each. “It was from her that I learned the more restrictive type of neraval, a characteristic of the Musiri school, that of keeping each syllable exactly in place.” Now, he is adept at both styles of neraval, playing according to each artiste’s style.

After Ramakrishnan graduated with his Engineering degree in Electronics and Communication, he moved to Madras. Working in an IT firm located far away, weekdays left little time for anything besides work and commuting. He joined TK Govinda Rao for lessons on the weekends, having first been exposed to him at summer workshops at Balamani’s classes in Bombay. Lessons with Kanyakumari continued. Govinda Rao’s classes were revelatory for Ramakrishnan and a period of intense growth on multiple dimensions. Govinda Rao would take one rAgam on a particular day and teach some 15 compositions in it. “His depth of knowledge in the rAgam and the kriti-s were so thorough – he left us completely awestruck”. Every now and then some manodharmam aspects would be incorporated. “They would sound simple – but the concentrated essence within it was incredible – it would be so difficult to replicate.” Recording and notating was not permitted. Imagine learning multiple new kriti-s in the same rAgam on one day with no recording to go back to! That rAgam would be revisited only weeks or months later. “It was only through sheer repetition over a period of time that I began to get it,” says Ramakrishnan. “When he did come back to that rAgam, he would clearly remember what he had taught and where he had left off.” He refers to Govinda Rao’s commitment to the art with abiding respect. “He would sleep only for a couple of hours a day and, even that, on his chair. Every waking minute was with music – he wrote so many books and was constantly engaged in singing or documentation”.

“He really tuned my ear very acutely,” says Ramakrishnan. “He required us to pick up what he sung very quickly. He would also sing very softly and he expected us to hear it. It has helped me so much in my career. I assimilate new songs/aspects very quickly now. Also, regardless of how light a singer’s voice might be, I can hear it and pick it up. That is probably also why I do not need much volume either,” he says.

Govinda Rao also taught Ramakrishnan the importance of being prepared and alert always. He refers to an instance where he accompanied him at a concert at Marundeeswarar Temple. The main piece tiruvaDi caraNam (kAmbhOji) and the tani Avartanam were over. Ramakrishnan imperceptibly relaxed. Now it would be tukkada-s. Govinda Rao threw a googly. He sang Adhaya Sri raghuvara in Ahiri….with kalpanAswaram-s! “I knew Ahiri. But never had I thought of swaram-s in the rAgam!” He was found out right there on stage. It is difficult to handle criticism in public at any age, and Ramakrishnan was just 22 then. However, he took it constructively. “There was nothing wrong with what he said. He was correct. It was an excellent lesson for me. I learned to be prepared for anything, literally. Needless to say, I came back home and practiced Ahiri the entire next day!” The sense of positivity and possibility is an integral part of Ramakrishnan’s mental make-up. “I believe I can surmount any challenge if I put in sufficient effort.” Govinda Rao would also praise. It was harder to come by but it was equally public. “He was, at heart, a very kind and affectionate person,” Ramakrishnan says fondly.

Calling him “an artiste of rare musical acumen”, Abhishek Raghuram says, “I know Ramakrishnan since 2008 when he used to come home to practice – we would play one rAgam for hours together. He has the amazing ability of explaining the most intricate nuances in a very simplified manner.”

From 2006-2009, Ramakrishnan was an active performer in the Chennai music scene. In 2009, he left for the US on work. He is most candid about why. “I had just bought a flat in Chennai. The monthly payments and the EMI seemed forbidding and as though they would go on forever. The higher income from an overseas assignment would help me defray those payments faster”. He was away for 6 years in Connecticut. When he informed Govinda Rao, he was told to seek out a man called Balu there (which was all the information he had been given). In Connecticut, he led a very frugal bachelor life, single-mindedly focused on earning as much as possible, and as quickly, to defray the payments on his Chennai home. He got married in 2011 and returned to Connecticut with his wife.

Govinda Rao had asked Ramakrishnan to look up ‘Balu’ in Connecticut. As the couple began socialising, they found him at a Navaratri celebration. He was none other than B. Balasubrahmaniyan of Wesleyan University. Balasubrahmaniyan is a protégé of T. Viswanathan, the grandson of Veena Dhanammal and the brother of the famous dancer Balasaraswathi. Ramakrishnan began going to Balasubrahmaniyan every weekend where he would sing and also play the violin. In the Dhanammal bANi, rarely was anything written down. A notable exception was T. Viswanathan who had notated everything in full detail. Balasubrahmaniyan, having learned from Viswanathan, had all the latter’s notations. “A small phrase would have 20-30 notes; even the tiniest nyAsa swaram would be given. There would be nothing left out.” Wesleyan holds a treasure trove of the Dhanammal bANi in its repository, with the pAtAntaram preserved intact – many recordings are without accompanists or anything else to detract from its thorough comprehension. While Ramakrishnan did not perform much in this period (he did not visit India to perform), it proved to be a productive period of learning as serendipitously as he ended up in Connecticut. When he returned in 2015, he got back to the performing circuit quickly.

Ramakrishnan has listened to music every day of his life, he says. He stresses the importance of becoming familiar with as many songs as possible and in varied styles. He says that not ever having heard a song unnerves him more than manodharma aspects or not knowing a rAgam. He explains that songs form the bulk of the concert – if one does not know the piece, one has to be completely concentrated on looking at the artiste’s face and lips to just figure the piece out – one could not even pay attention to the percussion. Thus, listening to as many artistes of different pAtAntaram-s with a completely open mind will be most helpful for an accompanying violinist. Now, after years of doing so, it is unusual for him to come across a piece he has never even heard – unless, of course, it is a recently composed piece.

Ramakrishnan Murthy refers to him as “an exemplary musician” and says his own understanding of rAgam-s has been enhanced by L. Ramakrishnan’s nuanced knowledge gleaned from his vast repository of compositions. “This is evidenced from lecture demonstrations he recently did,” he says.

In his initial days on the performing stage, Ramakrishnan struggled with some of the more intricate aspects of layam. He recollects practicing with Abhishek Raghuram in the presence of Sangita Kalanidhi Palghat Raghu and putting in significant effort into this aspect of his musical growth. When it comes to pallavi-s (as in RTPs), he suggests looking at it as the pallavi of a kriti. It will be sung at least four times before it is the violinist’s turn. Memorise the pallavi, he suggests. Where is the tALam eduppu? How many kArvai-s after the arudi? What are the words and the lengths of the words? It might not come the first time. But it will fall into place quickly enough. For neraval too, if one has assimilated the words and their relative lengths, an accompanying violinist need not fret about the tALam or the naDai very consciously.

Many vocalists/instrumentalists do not put tALam clearly, particularly when they are at the height of the concert – one just sees a tap every now and then. Ramakrishnan says that it is important for the accompanying artistes to have the beat internalised like a meter within them. However, there will be occasions when one is still in a bind. When this happens, he stresses the importance of not putting the onus on the artiste at the centre. “They are absorbed in their own musical thoughts; one should not foist the responsibility on them,” he says. On such occasions, eye contact helps but individual responses vary.

Ramakrishnan says that learning from, and playing for, Govinda Rao has equipped him extremely well to handle issues on stage. He emphasises the importance of maintaining a cool head in performances. “There was a time when if I made an error on stage, it would upset me so much that it would cascade and become a string of mistakes. Mistakes will happen. For anyone. One might have even planned and practiced a particular korvai but it might not work on that particular day. We should acknowledge it and move on immediately. A sense of humour is critical,” he says. He adds crucial points. “If we insist on proving ourselves again and again, we can overpower the other artistes. The biggest challenge for an accompanying violinist is to control the impulse to play every time – we might know exactly what will come next and might itch to play it but one should think of whether it will accentuate the rasikA’s experience – on many occasions it actually detracts from it.” Good advice for aspiring performers.

The quality of sound systems is, of course, a perennial source of irritation domestically in Carnatic circles. Some know the sound system so well that they alter their singing according to it to provide the best experience for the rasikA. Others clearly spell out the volume levels for each artiste, ahead of time. It can also happen that after much balancing, some artistes ask for individual enhancement upon the curtain rising. “We have to accept it whichever way it is,” Ramakrishnan says, in a circumspect manner. He believes the system of yesteryear, with one hanging mic for the entire team, often provides a better sound experience than the current system of a mic (or two) per artiste.

The biggest challenge he finds, is perfect sruti alignment. “There are so many instruments to align together – the electronic tambura, the acoustic tamburA-s (often two of them), the mridangam, the upapakkavAdyam and the violin. All of them cannot be in perfect synchronization. Mridangams and kanjira-s are made of hide and its tone and sound can change midway based on pressure exerted. The violin and the acoustic tambura-s have strings that are malleable and ductile. All these instruments are affected by external factors such as air conditioning, fans, temperatures and humidity. For those rather sensitive to such discordance, it can be a very tough exercise to tune the instrument to satisfaction,” he says.

Whenever he is not travelling, he practices every day. On concert days, he might warm up for a half hour or so, but on other days, he plays the violin for 1-2 hours daily but is with music for 7-8 hours daily, listening, humming, ruminating and reflecting. One aspect of that practice is to listen to a vocal recording and practice vocally during the violin interludes. “While listening, I constantly think on how to further improve my playing – what note could I accent better; should I play it in a different way? There is so much one can learn if we are consciously observant.” Ramakrishnan noticed, for example, that in flute concerts, if the violin is played in the same octave, it often drowns out the flute. So, he often switches to a lower octave so that the flute is heard distinctly. This can also occur with certain vocalists whose voice might be of a lighter timbre.

The violin’s string(s) can sometimes snap in the middle of a concert. “It definitely happens,” says Ramakrishnan. It takes him just a minute or so to replace it and get back to playing. How the other artistes on stage react to this varies – some would proceed unruffled, perhaps singing a long kalpanAswaram at the time to aid the violinist. Others can get flustered resulting in a resounding silence with the spotlight on the violinist. One should be prepared for any such reaction and should stay calm and get back to playing as soon as possible.

Carnatic music is still a spontaneous art form with its interesting moments. Often, one just has to figure out what to do next impromptu. Ramakrishnan recalls one incident. He was playing for Ranjani & Gayatri who sang rAgamAlikA swaram-s in two different rAgam-s. Ramakrishnan proceeded to respond with a third rAgam, much to the amused surprise of the sisters – his thought process being that they had sung two different ones and therefore, he was to play a third.

Ramakrishnan also advocates physical exercise. He says that he suffered from back issues for many years, a common ailment since violinists are frequently stooped over their instrument for the entire duration they play. He started visiting Movement Inc., a gym, where customized training is given for each person’s unique circumstances. He says he saw immediate benefits and suffers no pain anymore.

He advices artistes to record themselves and listen carefully. “It is often something we resist, but it HAS to be done. Only then can we know how we sound and what can be done better.”

Well written. Have known L Ramakrishnan as a Mumbai based violinist, but this article gives an extensive background. Wishing the artist many more accolades in future.

Extremely inspiring!

V well written Vidya. I know Ram and his mother Vasanthi personally. She is my friend from school. Great initiative from you that we get to know about artists . Read the article from “Hindu” paper also.

How nice. Thank you for writing, mami.

I am Ramakrishnan’s maternal uncle, have seen him growing up. My heart swells with pride looking at the heights our little boy has reached but his humility has always touched the right chords in me to stay grounded. Even after achieving so much praise and accolades, his demeanour is one of a student for life. He is pure dedication personified. Whatever he does, he strives for perfection, a characteristic that runs both on his paternal and maternal family trees. I can only wish him great success.

Thank you for writing, Sir.

Very inspiring article anna ! Great example for next generation aspirants.

As usual, ery nicely captured!

Sri Ramakrishnan is one of the few finest violin accompanists whose support is always very sensitive & melodic.

Hoping to see more such coverages from Smt Lakshmi Anand in the days to come!

Thank you!

I have been following Ramakrishnan before and after. I was wondering how such a wonderful artist vanished suddenly. Then on his return to rule we had the reason. Now if Ramakrishnan is playing you can consider it a top performance. More than anything his simplicity and easy approach is an asset. Wish him God,s grace and many accolades as time progresses.

I may add Iam Asst. Sec’y of HAMSADHWANI.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts.

Great interview, great writing. Interesting details very nicely captured and brought out. Thank you for this piece, Smt. Lakshmi Anand.

Thank you for reading.

I have listened to over hundreds of concerts of L Ramakrishnan and he was recently accompanying my grand daughter’s mridganga arangetram in Chennai couple of weeks ago. With his cheerful face and constant encouragement, Laya played reasonably well for her maiden performance, being a young girl born and brought up in US. I wish him a great future and gain more laurels and even, one day, Sangita Natakami award and/or Sangita Kalanidhi award

Thank you for writing in, Sir. Much appreciated.