Praveen Sparsh

Praveen Sparsh’s recent passion project, Unreserved, puts the mridangam in settings outside its traditional confines, and marries it with sounds he painstakingly recorded over the years on treks, at traffic signals, airports, rail and bus stations. To hear music, or the potential for music, in noise – or what the vast majority interprets as noise – is but one of the abilities this perceptive musician with multifarious interests possesses. Using technology to stretch and compress sounds as needed and pairing those with solo mridangam sequences, the result, surprisingly, is a cohesive piece that might be in a genre of its own. Be it traditional Carnatic concerts, or collaborating with other genres, or film and theatrical productions or creating his own tracks, Praveen straddles several creative spaces seamlessly.

In the Carnatic sphere, Praveen has earned the respect of the wide array of artistes he has played the mridangam for, including Dr. S. Sowmya, T.M. Krishna, Aruna Sairam and Bombay Jayashri. In T.M. Krishna’s words, “As a percussionist Praveen is wonderful to have on stage. He is adaptive and always a part of everything that is happening, even when he is utterly quiet. He is the first person who comes to my mind when I think of an ‘alternative’ idea or project, simply because I know he unhinged from compulsive habits that masquerade as tradition. At times, I have worried about Praveen doing too many things in many genres at the same time and wondered whether that would affect his ‘centering’. But he has navigated these phases and is slowly finding his own sound. In his sound there is a warmth that is unusual – even while playing aggressively, Praveen never sounds harsh. During the recent ‘Friends in concert’ production he played a fabulous passage of tAnam on the mridangam. I only told him that it should structurally be tAnam itself and not fall into a 4/4 grove. He worked on it, we discussed it during the rehearsals and what he finally presented was just outstanding. Praveen never over projects his playing, but its impact is felt in the entirety of the music that is produced. He does not take his talent for granted and more than anything else has realised that music does not reside in technique and versatility.”

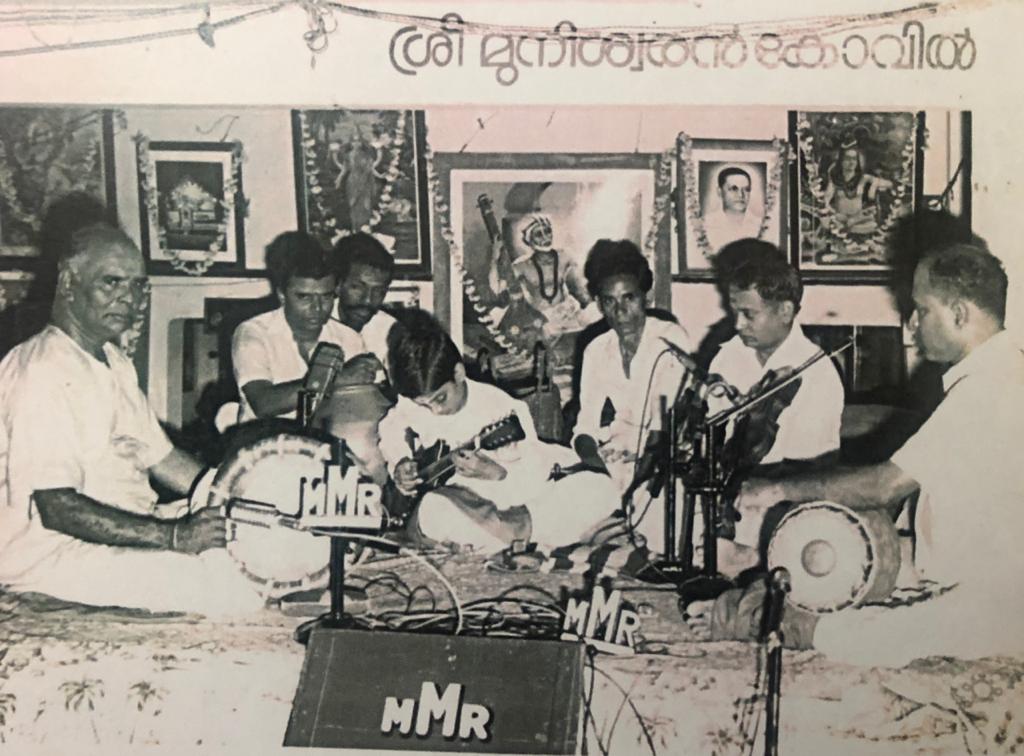

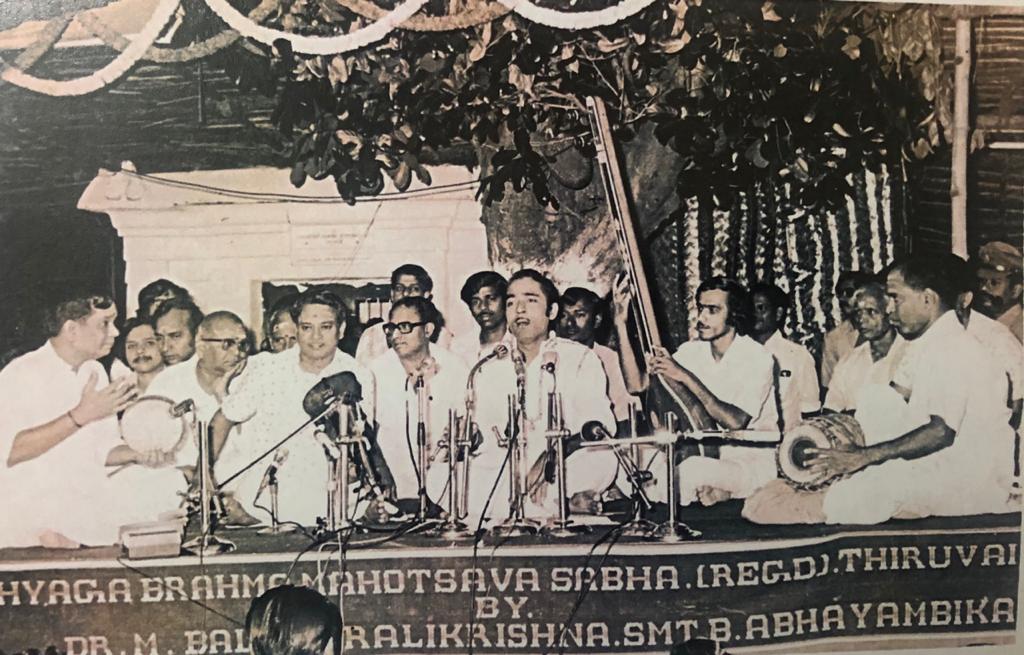

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu newspaper. (Photo in The Hindu by Sri. Nick Haynes). Many thanks to Sikkil Sri. B. Balasubramanian for sharing anecdotes and vintage photographs from his personal collection for this article and to Sri. Praveen Sparsh for locating other photographs and making a video especially for this page.

28-year-old Praveen Sparsh, aka Thanjavur Praveen Kumar, an Electronics Engineer by qualification, is the grandson of highly respected mridangist Thanjavur Upendran, and great-grandson of renowned tavil exponent Valangaiman Shanmugasundaram Pillai. Articulate, soft-spoken, thoughtful and very measured in speech, Praveen displays a steely resolve in his serious, impassive countenance. No topic is off-limits and he ruminates over each question carefully to give a meaningful answer.

Born several months after Upendran’s untimely demise in 1991 at the age of 56, Praveen never met his grandfather. His aura, though, has been a continual source of inspiration. Upendran, from all accounts, was a pathbreaker on many dimensions. A left-handed mridangist, his style incorporated tavil techniques and kaNakku-s (calculations). He customized his playing to each artiste he played for with a finesse and style all his own. Besides his professional skills, Upendran is remembered as a thorough gentleman who uniformly elicited affection from those who knew him – Dr. Sowmya refers to him as a “fantastic human being”. At a time when age and seniority were unimpeachable, Upendran brought many artistes to the fore focusing only on ability, regardless of age – not just by playing for them but by encouraging stalwart contemporaries to do so as well. Veena exponent Kannan Balakrishnan might very well be the only one who has shared the stage with both grandfather and grandson – Upendran and Praveen. Kannan says he was a beneficiary of Upendran’s largesse. “Upendran mama along with Vinayakram mama (ghatam exponent T.H. Vinayakram) were kind enough to play for me, a young boy, at my maiden performance at the Thiruvaiyaru Thyagaraja Aradhana in the mid-70s.”

Photo courtesy: Sikkil Sri. B. Balasubramanian.

When an individual is a noted figure in music, the spectre of the art usually hovers over all in the family. Neither of Upendran’s two children, though, took up music. Praveen’s mother – Upendran’s daughter, K. Kumutha – listened to a lot of Swami Haridhos Giri’s bhajans when expecting him. That perhaps explains Praveen’s inherent and natural proclivity to Carnatic music that he adored. To his early teens, he listened exclusively to Carnatic music. However, neither his grandmother nor his parents ever planned, or intended, on his taking up music as a profession. He explains his start in mridangam thus. “My mother thought I needed an extra-curricular activity. Observing my tendency to tap on anything and everything all the time, she thought why not mridangam. I first joined a group class in the neighbourhood. That teacher thought I had potential. Nellai Balaji Sir then came home and taught me for some 4 years.” Attending a bhajan competition, Praveen saw B. Srivatsan play the mridangam and declared that he wanted to play like him. Enquiries were made and it was found that Srivatsan’s guru was Guruvayur Dorai whose tutelage he soon joined. Dorai’s senior student, Uzhavoor P.K. Babu was his primary instructor initially. Babu was a strict teacher and expected his students to produce their absolute best. Praveen says, “I would tell my mother to go to the nearby Sai Baba Temple and wait while I was at class. That was when she realised that I was rather serious.” Classes were in Dorai’s house itself with Dorai in the adjacent room. Regarding practice, Praveen is candid. “Though I enjoyed playing with others or as an ensemble, I would whine to do even short solo practices. My mother had to push me. She insisted that whatever was taken up ought to be done properly and that Guru-s felt the effort they put in was worthwhile.”

Later, he became part of a group class with other senior students, instructed by Dorai himself. At this point his mother asked him if he was willing to put in the committed, consistent hard work needed to do justice to that level of instruction – hours of practice prior to, and after, school too. By this time, self-motivation kicked in.

Praveen describes learning from Dorai. “Sir was most mild mannered – one had to be extremely attentive to each of his movements AND his words. Most of my learning was from his live concerts – carrying his instrument, going with him, listening, coming back home, unpacking his instrument. Having dinner at 11.30 at night. I had just a few lessons in notebook – the rest was just experiential. For an entire year, I understood nothing.” He likens it to his first two months at Vishnu Sahasranamam classes when he did not follow anything. “Then I start chanting along.” Similarly, he started figuring out tALam-s, different placements on the mridangam, what was being appreciated, what was gelling well with the other musicians etc. “I had to be on stage to absorb what is happening – to feel the energy.” It is to be noted that when students sit on the stage behind mridangists, they are unable to see the dominant side (valantala) of the mridangam – yet, Praveen, like many others, expresses immense value of on-stage observation at concerts. So, did he return from concerts and ask questions of his Guru? “He was so much older. I never would pluck up the courage to just speak to him and ask questions. Sometimes, he would ask me if I noticed something different.”

From the mridangist’s perspective, there are two key aspects that have to both work together – firstly, coming up with calculations (kOrvai-s) that fit the count of the tALam and, secondly, doing so in a manner that fits the composition being rendered and the individual artiste rendering them – this second part is the challenge which takes multi-factorial skill – listening, observing and applying it uniquely and appropriately to each moment. The music is not metronome driven, and he remembers his mother commenting during practice that he was playing something but it just was not connecting. “I might have been told, for example, to make a kOrvai for 64 mAtra-s (subcounts). I would come up with something that was mathematically correct but aesthetically terrible and made no sense. I have done a lot of that. You potentially have the world as your oyster but you cannot do whatever you want. There have been cases where I have listened to recordings of stalwarts, picked up something from there, incorporated it in a piecemeal way but the result would have no continuity. It is a lot of enthusiasm which produces a platter that seems interesting but just does not work.”

Praveen’s first concert was at the Besant Nagar Varasiddhi Vinayakar Temple at the age of 8 where he played the mridangam for his Bhagavad Gita Teachers. He was then part of several small concerts subsequently. At the age of 14, he won the Spirit of Youth series at The Music Academy. That usually entails a slot to perform at the following year’s regular music season line-up. However, since a performer pulled out at the last minute, he performed that very year, playing for the late Ranjani Hebbar. He won the Best Instrumentalist award for his performance. It was a shot in the arm and propelled him to work even harder.

Praveen’s father, G. Kishen Kumar, was a key part of his concert excursions as a child – “Carnatic music does not resonate with him at all. Yet, he would take me to every concert without any complaint and wait there until it was time to take me back home. Knowing that reading a newspaper was inappropriate, he would not do that either.”

T.M. Krishna explains his initial exposure to Praveen. “I first saw Praveen as a 14-year-old little boy who many said was talented and had a future in Carnatic music. The added attraction was the fact that he was the grand-son of the much respected Thanjavur Upendran. I lost touch with Praveen for many years after that encounter, though I saw him a few times coming along with his guru Guruvayur Dorai to concerts where the great man shared the stage with me. Much later, when I heard him play again with some of my students, I immediately knew he was a special artiste.” Kannan Balakrishnan says, “Upendran mama‘s special touches have passed on to Praveen who reminds me of his grandfather.”

Lessons in Carnatic music, irrespective of vocal or instrumental, typically begin with exercises in a prescribed order to be rendered in a particular way. Yet, the music, at the concert level, is driven by extemporaneity that requires improvising on the spot in tandem with the other musicians on stage. This step, of how one moves from purely reproducing what is taught ‘kalpita sangItam’ to ‘kalpana sangItam’ – literally ‘from the imagination’, as in following the music and apply one’s learning to each individual circumstance, is often not articulatable. Musicians themselves are rarely able to explain how exactly they acquire this skill, but Praveen gets there better than many.

Learning to accompany happened in one class, says Praveen. “Sir would sing in class – we would even have impromptu rtp (rAgam tAnam pallavi) sessions. One day he said, “I see you are playing some small concerts. What are you playing for the songs?” I said, “You have taught me some tALam-s, lessons and naDai-s – I superimpose those on songs.” That day, he sang sogasugA mridanga tALamu. I was looking only at his tALam and not at him. After the pallavi, he stopped and asked, “Are you listening to me?” I said, “Yes, sort of.” To which he said, “I am hearing what you are playing, as a singer. You should be hearing what I am singing as a mridangist. If you are taking only the tALam as a medium, you are playing a solo. But this is an ensemble.” That one class changed me. I realised I had to understand the vocalist and his/her decibel level and try to play with that. Only if you start to collaborate at that level will the energy transfer. I extended that to listening. How has Sir played for MS Amma? For Veenai Balachander? How does he play differently for different artistes – male, female, vocal, instrumental etc.?”

For Praveen, the difficulty in the art is not in executing techniques or lessons. “If we practice, we will get some version of that lesson. It is more about how to achieve the impact that you palpably feel whilst listening to others. The aura that someone conveys. The first time I heard Zakir Hussain, for example, I asked very serious questions of myself. I was so uninspired to even play for the next couple of days. This happens whilst listening to old recordings too. If you attempt reproducing what they did, it sounds so flat. You keep listening to get a grip of that feeling – then you do something with the feeling rather than an exact reproduction of the sound. That is very hard.”

Regarding practice and whether he would play along with recordings, he explains. “One should practice, listen, then mentally map what was heard and convert that to practice. Rather than sitting with an instrument in front of a recording, I would listen carefully, then try and translate.” Flautist J.B. Sruti Sagar was his neighbour on the same floor of his apartment block. “He would practice for 4-5 hours a day – if there was a kRiti I had heard that I wanted to play for, I would ask him to play it and I would play with it. He would ask what kOrvai I was learning, put tALam for that and we would come up with something together. B Srivatsan was also there to practice with. It was a process of listening to recordings and then practicing live with musicians.”

Here, Praveen shares what Dorai told him about developing one’s own style. “He said – I am playing a certain way now. But don’t just look at that. Remember that this is my body and my tutelage. Listen to my old recordings and those of others – see the evolution. You should do something with what you hear and see but not do exactly what I do. Everyone should be unique. You should learn everything I teach but not stop there – you should come up with something yourself.” This probably encapsulates what is the best, yet most difficult, part of Carnatic music – to absorb, emulate even, but branch out on one’s own, but with direction and without blindly copying.

Active listening, with a view to learn, is an art by itself, says Praveen. “In 10th grade, I saved up and got a 160GB Ipod – all of it was Carnatic music. I filled it with collections from my Guru and from my friends. Your perspective of how you listen changes – what is the fingering of what he has played – I can picturize some of it mentally – where on the surface of the mridangam he would have tapped – what happens between the musicians – how is the vocalist reacting to what the mridangist is doing etc. – you start noticing gradually.” Praveen says that he can mentally map most sounds as strokes on the mridangam.

Testifying to Praveen’s appropriateness in accompanying, Dr. Sowmya says that Praveen exhibits a remarkable sense of proportion belying his age. “Someone that young could often get carried away by exuberance and look only at rhythmic aspects. But he plays so sensitively for the composition, enhancing it and making it stand out. Playing for padam-s, for example, is particularly difficult if you do not know the subtleties. But even when Praveen played for the very first time for a padam, it was so beautiful. I enjoyed singing it so much – his interspersing the pauses with the music of the mridangam – after a very long time, I felt so happy singing that padam. If I were to perform a program of only padam-s, I would undoubtedly choose only Praveen on mridangam for that concert.”

The feeling seems mutual. Praveen says that playing for Dr. Sowmya is most educative. “It is such ‘maDi’ (correct, proper) music – a very different experience. Her ideas in swaram and rAgam are just brilliant – so inspiring. Her paddhati (methodology) is so scholarly. She is a powerhouse of knowledge, and to travel with her is an experience.”

Praveen chooses his instrument according to each artiste he plays with. He plays both the kappi (specific kind of tiny pebbles inserted between the layers of hide on the dominant side of the mridangam) and the kuchchi varieties (thin reeds between the layers of hide) mridangams. The two varieties offer different tonal qualities. Praveen plays the kuchchi with the nadhaswaram and tavil, for example (Praveen and his wife, violinist Shreya Devnath, perform as a quartet with nadhaswaram artiste Mylai Karthikeyan alternating with tavil artistes Adayar G. Silambarasan and Gummudipoondi R. Jeevanandham). “But for the same pitch, if it were veena, I would select a kappi mridangam, for example, which would produce the more appropriate mellow sound required for that instrument.”

It was his school, Chettinad Vidyashram, that exposed Praveen to other musics – he would spend hours in the music room there. He makes particular mention of the school music master Suresh, who would compose and arrange a unique piece specifically for the school students for the annual day. Praveen remembers declining to play the drums when requested by Suresh, stating that his Guru (Dorai) would not approve. What he had not counted on was Suresh personally visiting Dorai and asking his permission, which was readily granted! After that, Praveen was a regular at the school programs, often playing a wide variety of percussion instruments.

This exposure also got him to begin listening to Bob Dylan, Bob Marley, The Beatles, jazz, film music and more. The configuration of that Ipod changed, featuring independent artistes that were neither classical nor film musicians – a whole new world. Initially resistant, the other genres began fascinating him. He recollects listening nonstop for a week to Flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucia who made a particular impact on him. He explains. “Flamenco guitar is extremely percussive in nature. When he plays a riff in the guitar, he is also tapping, strumming – fanning in and fanning out. I began relating some of what I heard there with what I heard in, for instance, what (Umayalpuram) Sivaraman Sir does. You hear this on the guitar and you start to process that sound differently – how is that sound going to translate in the mridangam? Can it be translated? We have a 6/8 kaNakku in Carnatic – but flamenco translates that 6/8 very differently. First you process it and then you do something with it.”

Contemporary jazz fascinates him as well. “In one 30-minute piece, they scale through so many time signatures. If even one person makes a tiny mistake, they run through the entire program again for an empty hall. It is precision of an unbelievable degree. As an ensemble, everyone needs to be on point and calculate on the spot. Ghost notes (notes or syllables not heard distinctly but exist) are perceived, and operate, very differently in this genre.” To get some aspects of what he observes in those genres into mridangam excites Praveen. “These song writers are like vAgayekkAra-s – a lifetime of vision.” Dr. Sowmya appreciates his interest in these varied genres which, she feels, gives him an enhanced appreciation of the music he hears.

Besides Sparsh, the group he started, Praveen is part of Sean Roldan and Friends with whom he has extensively travelled. The passion projects he does independently are completely self-funded but bring in opportunities from those who see his potential in the soundscapes he creates. He was approached by renowned cinematographer Rajiv Menon, for example, to produce re-recordings (background music) for the movie Sarvam Thaala Mayam. Shreya and he have also done outreach programs for first generation school students, at their own expense.

Praveen (by himself, and with Shreya) has scored, and played, music for Gowri Ramnarayan’s productions. Gowri says, “Anyone who plays music for a play has to completely erase any sense of ego – viewers are watching the play and listening to the dialogue – not the kOrvai played. The play is supreme here. Praveen always puts himself in the background and the needs of the art first. He also comprehends the fact that I am the director and has never displayed any attitude. To ensure that the music is played such that the words are heard clearly requires thorough understanding of the play – which he displayed by interspersing the music at the precisely appropriate junctures. I received several comments about their subtle yet powerful work. For a young man to assimilate a range of emotions from the very human to the very philosophical is remarkable. I will give both him and Shreya the highest scores for intelligence – not just for their skills on the instruments and composing but for understanding the needs of the play. He is always learning and is excited to learn.”

T.M. Krishna has been a major influence on Praveen. “I first played for Krishna anna in 2010 when I was 18. It was a huge learning curve artistically and he has played a huge role in mentoring my artistic journey.” He explains Krishna’s impact. “Firstly music, and specifically kAlapramANam (speed) – as percussionists, we think we are very comfortable with rhythm and kAlapramANam, but it is absolutely not true – there are so many grey areas that can really make you uncomfortable. A very slow speed and a really fast speed can both really throw you off. There were times when I could not figure out the time signature of what he was singing. And figuring out what to play in a gap where he has just finished singing something with a huge flourish – you feel so insignificant at that point. To learn to get into his zone, to connect with the vocalist and the violinist – it is not a one dimensional concert – helped me to listen to everyone on stage better and get used to the different kAlapramANam-s, particularly the slowest one – and to realise that it actually makes sense to not play sometimes.

Krishna anna has shared thoughts about a lot of musicians and their brilliance – the insight of different eras and exposure to different co-artistes. It broke many mental shackles for me and played a huge role in how I perceive many issues. The Joggappas, for example. I went from being petrified of transgenders to being in a room with them and seeing them as artistes. Conversationally, Krishna anna would always engage. His flight journeys are never dull. If I disagreed with something, he would continue the discussion, the engagement. He will show possibilities and instances. Personally, emotionally and musically, he played a huge role. I am grateful for the faith he had in my artistry.”

Praveen raises some interesting points. “In Carnatic music, those on stage are usually seen in a pecking order – vocalist is 1st, violinist 2nd, mridangam 3rd and ghatam, kanjira or morsing 4th. But each one of these artistes is extremely talented and immensely skilled individually. The instrumentalists are sometimes even more skilled. So, what happens if you take that hierarchy away and mix it up? I have been learning that from Krishna anna. Why is violin and percussion referred to as ‘support’? Does one need crutches? Nobody is supporting anyone else. We all have our roles. The goal is to artistically collaborate on stage – this is very difficult to achieve but it happens all the time at Krishna anna’s concerts.”

He continues. “What if the ghatam or kanjira plays for kIzh kAla neraval (slower speed improvisation of a phrase or line with lyrics)? There are those who say mridangam should only play for the voice because the mridangam is louder. But what happens if I play with the violin? It is a new sonic possibility. Only if we remove these barriers can we explore. Nowadays, I think differently outside of Krishna anna’s concerts too.” He did that recently at Vignesh Ishwar’s concert, where Anirudh Athreya played the kanjira exclusively for Vignesh for an extended period of time and Praveen played for the violinist, Vittal Rangan. Praveen explains that if he intends something different from the ‘standard template’, he does alert the artistes ahead of time. He also admits he experiments more frequently with Krishna’s students than with others.

Praveen further suggests having a Carnatic repertoire specifically designed for instrumental music. This, he feels, might help one step out of the mental confines of expecting instrumental to ape vocal. Instrumentalists too wish to keep the vision of the composer who has usually composed with vocalization in mind. Instruments though, can go beyond vocal in some aspects and not in others. Therefore, a specific repertoire could address these issues.

He also says that it is not the type of music that makes some accessible and the others not – rather it is the fact that some types of music are played anywhere, whereas to access Carnatic, for example, one has to go to a sabha. Praveen also mentions occasions when rasika-s have been mocked for asking for certain pieces at inappropriate times – vAtApi ganapatim after the main item has been sung, for example. “Someone should have at least explained to those individuals why it was not done.”

We come to gender bias and the fact that many artistes avoid playing for women. “As a society, gender bias is common – it is there in everything – and particularly evident in this field. Shreya and I talk about this all the time. It is extremely unfair for the art form. As artistes, we have lost an entire texture of music. It might be more sowkhyam to play in D sruti but it would never stop me from playing for other sruti-s. It is exciting for me to play for females because it is a very different texture of music – and I like different sides of me to be tapped.” He enjoys playing for instrumental concerts too and the idea of playing without a tALam reference.

When an artiste plays the rAga AlApana, percussionists do not play. Does that mean he, as a mridangist, can mentally switch off then? Praveen says he listens very carefully to how the rAgam is rendered, because it is a preview of how the neraval and swaram will be sung. “If I am revising my own lessons or thinking of something else, it will make it difficult. Every crescendo and every ending will reflect the rAgam which are just the artiste’s ideas without rhythm. Additionally, for listeners, it is very distracting when artistes are uninvolved, so I ensure I pay attention.” When it comes to the song itself, he notes how the words are split and follows that. “If the music speeds up or slows down and I insist on keeping the initial beat, it will ruin the program. I cannot just be a beat keeper. I have to go with the other artistes and try to maintain a balance.”

A key requirement for every accomplished percussionist and accompanying violinist is for the tALam to be completely internalized within them without requiring an external reference to it, even for neraval and swaram. How does one acquire this skill? Praveen tries to articulate his own journey in this aspect. “I would first play the lesson, consciously playing the tALam in mind too. Then, I would say the lesson (in konnakkOl syllables) with tALam. I then played my lessons with a metronome – it was not my Guru’s stipulation, but I was fascinated with technology. Then, I switched off the metronome and used my foot alone. Over time, it internalises. This works with every tALam.” This, he says, is crucial.

His students, Praveen says, get chided mainly for not having this internalised metre within them. “I will stop lessons midway and ask where the tALam is.” He has five students currently, two of whom started from the very beginning. “My training is very individual based on each student’s inclinations and existing skill sets.” He found his youngest, who is 8, most interested in cricket. To break the ice, he started with ball exercises where the number of bounces is the number of aksharam-s (beats).

Video courtesy: Smt. Shreya Devnath via Sri. Praveen Sparsh.

In terms of practice these days, Praveen plays the mridangam whenever he feels like it rather than setting specific durations. “More than playing, I train my mind before a concert. If I play a lot before, I could get tired. But I storyboard the concert in my mind in detail – anticipating the song that will need the physical abilities, the song that will need the mental abilities etc. I do not have any specific rituals before concerts. That is similar to Krishna anna who too does not have a ritual. We have gone to movies in the afternoon, eaten chaat and come on to stage right after.” Praveen also mentions the importance of brushing off earlier mistakes. “I will train my mind to not focus on what has happened – on stage, your decisions need to be clear, and cannot be clouded by the past.” It is not easy. “When I make a mistake, yes, it stays in the back of my mind. Ideally one should push that away and focus on the task at hand – to the extent possible, I do that. Even if it is only a mangaLam left, the ultimate act of finishing a concert is in one’s hands and it is an important responsibility.”

As to what he hopes to do and achieve at a concert, he says, “I try to listen to the stage and try to react appropriately. Secondly, I try to egg on the other artistes – the trigger should be inspiring enough to be noticed and take off from – it is not to impress but to kindle. That is how I approach accompanying. The idea is to be an ensemble, be supportive and influence their decision making in a healthy way – to make some magic happen together. I honestly try to give my best to inspire other artistes on stage.” His favourite part, he says, is neraval and swaram.

The percussion solos (tani Avartanam) in concerts are not regulated in terms of time but can come in for quite some discussion particularly if one ‘overshoots’ that unspecified duration. Praveen uses a mix of various factors to calibrate himself here. “In a 3-hour concert, I might do 25 minutes. It would be much less in a 1.5 hour concert. In one of Krishna anna’s concerts, there were 3 tani-s, each for 15 minutes – that became a very percussion-oriented concert. Besides concert duration, I consider what the artiste has sung, the kind of music that has flowed, what the audience is like etc. If the artiste is already thinking of what tukDa to sing, I will finish quickly. Some artistes ask percussionists to play more – in that case, we do. But the tani Avartanam always begins as a blank slate.” What exactly he plays in the tani is spontaneous and also influenced by his co-percussionists. He recollects one tani at a recent concert with Bharat Sundar where G. Chandrasekara Sharma was on ghatam. “I started with kanDa naDai. Chandru played miSra naDai. I thought it sounded very nice. I took up miSra naDai too. Then he played sankIRNa naDai, and we finished with tiSra naDai. That tani was artistically driven by Chandru. Bharat had asked us to play at length that day as well.” Praveen adds, “The non-mridangam percussionist not ‘following’ what the mridangist does is also frequently considered offensive – another barrier we should try to break.”

According to Dr. Sowmya, Praveen is very meticulous, systematic and correct in all his actions. “He will listen carefully to what is said, think about it and will get back at the time he said, with results. For the Carnival’s (Sukrtam Foundation’s Music Carnival) offline puppet show production, I had envisioned a story voiced by several 2-4 year olds. He made such beautiful art out of the multiple individual raw audios we gave him. He gave me so many ideas for designing the stage too – Shreya, Praveen and I did that together. For the online shadow puppetry done for the 2020 carnival, Shreya and Praveen choreographed the music so well. It was incredible. It is as though we give him an unpolished black stone and he makes it not just a diamond but a piece of finished jewelry with it. I have travelled with him a lot and he can speak on so many topics that he sometimes reminds me of the Pacific Ocean – vast knowledge, cool, calm and expansive but we do not quite know the depth and the profundity of his knowledge. If there is one thing I wish he would do more, it is smile,” she says – with a smile.

Praveen is financially self-sufficient through music alone. His non-Carnatic musical projects and activities offer a further cushion that allows him to be discerning of the opportunities he is offered. He readily explains the rubrics he uses to decide whether or not to accept an engagement. “If it is a really good musician, I accept immediately. If I am not too curious about the artiste(s), the payment is the deciding factor. I should say here though that money alone will not make me accept a concert – if there is an alternate unique opportunity, I will turn down a higher paying gig.” He also makes time for himself and his other passions like trekking too. “For a performing musician to take 15 days off is rather unusual and some senior artistes do get offended.” All of us go through a trajectory in communication and Praveen is candid about his. “When I first began, I would speak without thinking, dress the way I liked and did not worry about being judged for those decisions or even if I made it in the industry or not. As I got older, maturity set in. My partner, Shreya, also made me aware that there are better ways of expressing myself. So, while I am truthful and matter-of-fact, I respect anyone who has reached out no matter who he/she is and treat everyone the same way. It is a business and a business opportunity.”

Has he faced discrimination from not being a brahmin? “Not very overtly or literally. I remember going to Mantralayam years ago where I had to remove my shirt. I was asked why I did not have a pooNal (sacred thread worn by brahmin men and a few other groups). On tours, some hosts have automatically assumed I am non-vegetarian. But I am vegetarian. At some level, I just became numb to such occurrences – probably not very different from how women normalise gender bias. ” In terms of opportunities, he says he has no way of knowing if he has faced discrimination on this count. “My friends have never seen me differently.”

A now-amusing (then nerve-wracking) incident occurred some years ago when Praveen was in Israel along with T.M. Krishna and violinist H.N. Bhaskar. They were to cross Palestine that day and had specifically been told to carry their passports and visas. Praveen, sometime after the journey began, realised that he had not taken his paperwork with him. On the return, they were stopped, with their Israeli guide questioned intensely and quite aggressively. Identifications were asked for. All Praveen had was his Aadhaar card. The Israeli official, taking one look at it, just tossed it away. It took some wrangling before their party was allowed to proceed. “I have never lived it down – I took my Aadhaar card to Palestine!” Praveen says with an embarrassed smile.

Krishna shares further thoughts on Praveen. “It has truly been heartwarming to watch Praveen grow as a human being and an artist. He has always had a curious mind and engaged in discussions that would make many others uncomfortable. I vividly remember the conversations we had on a short trip to Srirangam when everything from music, caste, gender to alternate universes were discussed! This ability to be open, observe, absorb and think on his own sets him apart from most artistes in his generation. He would tell me softly or gently indicate that he disagrees with something I have said or written, but I know it is a strong opinion! I have heard some artistes say that he is constantly speaking in a serious manner, some even think he is ‘trying too hard to be intellectual’, but what they do not realise is that this quality to reflect lets him grow beyond any specific confines.”

Related Articles: Legacy – A boon or a bane?

Loved the article Vidya.

It is isn’t just about these super-talented artists. I learned so much about the nuances in the talam, and the music just by reading your article.

You are a prolific writer and a gift to the world of Carnatic music.

I sincerely appreciate your constant encouragement, Gita. Thank you.

That was a terrific interview. No cliched questions, kept the conversations flowing with ample amount of information in each line. Great collation of the interview too at the end.

Thank you for reading and for the kind words. Much appreciated.