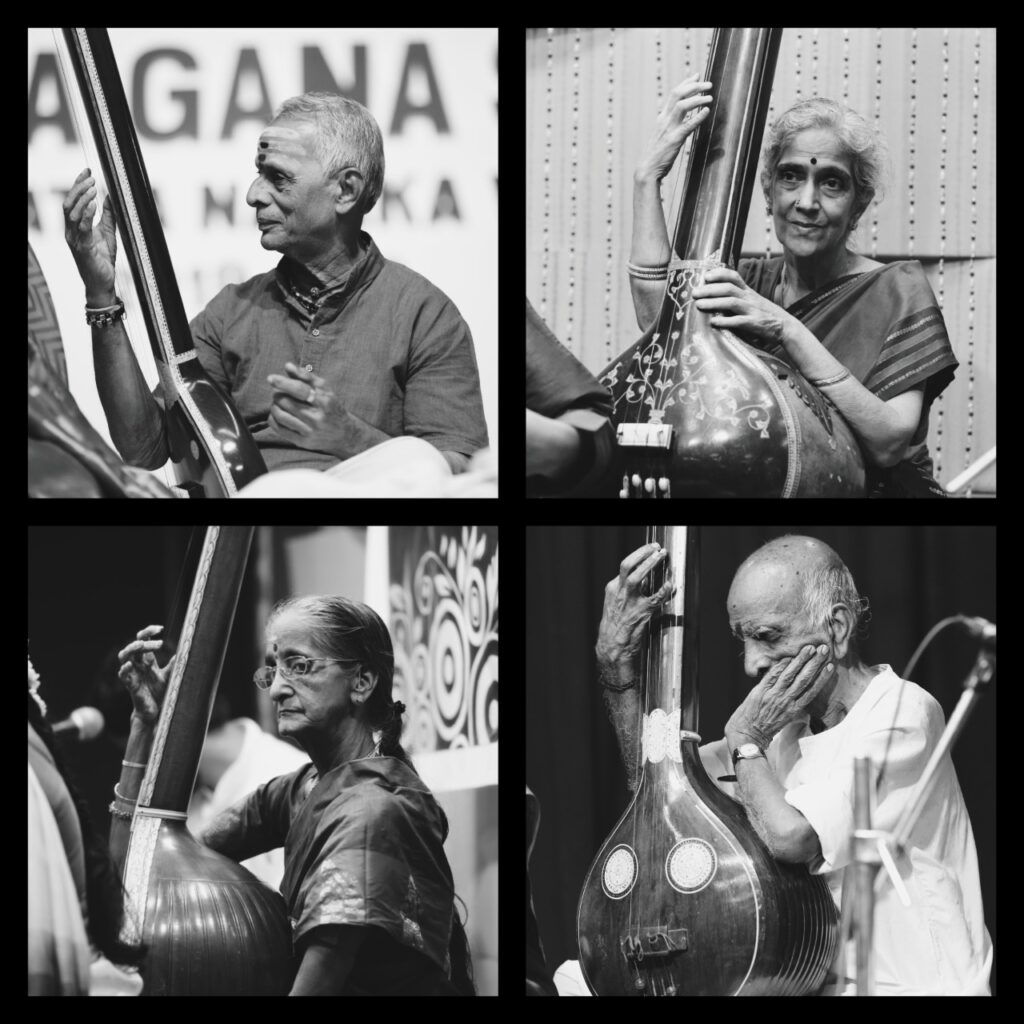

The Endangered Tambura Artiste

R. Lakshminarayanan, R. Vaidhyanathan, Latha Venkataraman and Kalyani Viswanathan have been on the most prominent of Carnatic concert stages for 15-50 years. Yet, most readers would not know who they are. They are tambura players – unknown, unnoticed and mostly uncredited.

Vocalist Nisha Rajagopalan cannot imagine performing on stage without a tambura player. “I practice with the tambura at home and there is no substitute for it.” Vignesh Ishwar, vocalist, says, “The tambura player is critical to a concert. They can set the tone for the entire program.”

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu newspaper dated December 3rd, 2021.

My sincere thanks to Prof. S. Chandrasekhar of IGIDR Mumbai for igniting the barest flicker of an idea and to Smt. Jayalakshmi Balakrishnan of Naada Inbam (Chennai) for providing invaluable assistance at multiple levels. I am very grateful to Sri. R.K. Shriramkumar who spent significant time patiently and clearly explaining technicalities and details. My thanks to Smt. Nisha Rajagopalan and Sri. Vignesh Ishwar for their comments on short notice.

A decade ago, I asked a gentleman I did not recognise as to his role in the upcoming concert. “I am a professional tambura artiste,” he bristled, lifting up his small frame to its fullest – the first I had heard of such a term. Senior musicians and those of some stature or recognition frequently have their students strum the tambura for them. In other concerts, there is no tambura player at all, the electronic versions alone being deployed.

With many alternatives available, I wondered how and why these dedicated tambura players took up this vocation and set about finding out. By all accounts, these four individuals are respected, even beloved, for their skills on the instrument and decorum on stage. In fact, many musicians told me that their first task after accepting a concert is to book their preferred tambura player! It is a fine line, they say, between a tambura player being involved and attentive to being intrusive and disturbing. Musicians mention some who begin singing along during the program, for example.

Good tambura artistes can leave an impression in the minds of artistes and rasikas even after their demise. The late Saraswathi aka Rani Anantharaghavan is mentioned by all, both for her impeccable strumming and her radiant and cheerful presence. Tambura Ganesan is also fondly remembered.

To the external observer, playing the instrument might seem simple but senior musician and teacher R.K. Shriramkumar says it is not. “How it is played is critical,” he explains. “Keeping the fingers parallel to the strings, gliding the finger (not the nail) gently from string to string, the kalapramanam of the strumming and its regularity – every aspect is important and none of it is trivial.” Shriramkumar adds that the force applied on the strings requires changing spontaneously if the sruti in the instrument alters midway, requiring the tambura player to be sensitive to the overall sound.

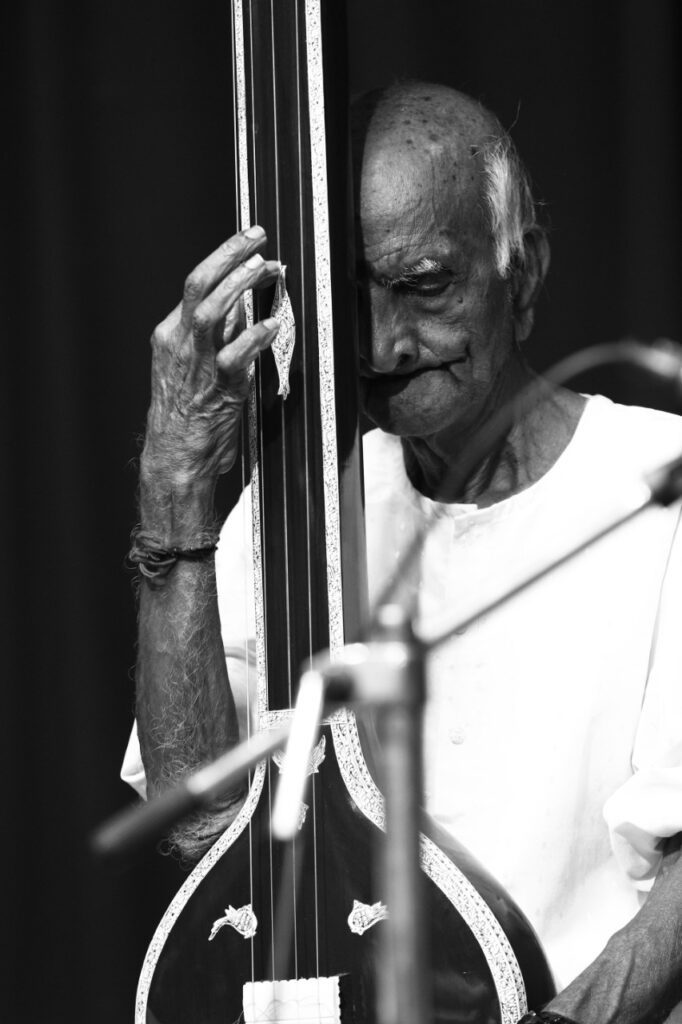

With over 50 years of playing of the instrument, R. Lakshminarayanan, 93, could very well be the longest serving active tambura player. His brother and he performed decades ago as a vocal duo known as the Vellore Brothers. Lakshminarayanan learned vocal music from Chittoor Ramachandran, a nephew of Chittoor Subramania Pillai. He has passed higher level examinations in both vocal and flute and has played the kanjira too. He taught music privately for many years. He has played the flute in dance performances for K.J. Sarasa, Swapnasundari, V.P. Dhananjayan, Adyar Lakshmanan and more. He has played the tambura for T.R. Mahalingam, K.B. Sundarambal, Madurai Somu, N. Ramani, T.S. Sankaran, T.V. Sankaranarayanan and others. He has been a casual artiste at All India Radio and Doordarshan and has played the instrument at many dance performances too.

He is one of few tambura artistes who can tune the instrument completely by himself. As a result, if the sruti changes midway, Lakshminarayanan adjusts it promptly himself usually even before the artistes notice. Jayalakshmi Balakrishnan of Naada Inbam says that these skills elicited the praise of the discerning late violinist T.N. Krishnan himself. Lakshminarayanan tells me that the expertise stems from his having been a technician at the famed Sangita Vadyalaya, assisting musicologist Prof. Sambamurthy in manufacturing tamburas, veenas and other traditional Indian instruments. Lakshminarayanan then naturally segued into tambura playing.

Kalyani Viswanathan, 67, who has been playing the tambura for over 15 years now, spent many years in Bombay where she was convener at The Fine Arts Society, Chembur. She was then focused on raising her son, violinist Bombay Anand, and would fill in to play only when needed. When Kalyani moved to Chennai after her husband’s retirement, she began playing the tambura during the music season and now plays regularly. She tells me that she enjoys experiencing the music at close quarters and often asks artistes about pieces they have sung, ponders on interesting talams she has seen on stage and so on. She often goes beyond playing the tambura, lending a hand to organisers and artistes with accoutrements on stage.

R. Vaidhyanathan, 73, draws positive mention from rasikas, in-person and online, for his very discernible enjoyment of the music as he plays the tambura – manifesting in smiles, thoughtful expressions and gaze moving from artiste to artiste during exchanges. His father, Thirukokarnam Ramachandra Iyer, was a vainika of the Karaikudi bani. This inculcated a love for the music and its intricacies in Vaidhyanathan who himself learned veena until varnams and subsequently taught basic vocal lessons to neighbourhood children. A BA in History, he was professionally employed before taking up the tambura full time 25 years ago. He has shared the stage with M. Balamuralikrishna, Bombay Sisters, P.S. Narayanaswamy, Mandolin Shrinivas and several of the current performers. A precious moment for him is dancer V.P. Dhananjayan mentioning him specifically in his comments after a concert. Despite suffering from fractures to the leg and back, Vaidhyanathan has indefatigably kept up with tambura playing. “I come for the music which I so enjoy,” he says. He appreciates the artistes treating him with respect and referring to him as ‘tambura mama’.

Latha Venkataraman, 69, has been a tambura artiste for 18 years now and recently played at her 1,251st concert. Her siblings and she did not learn music but were within earshot of it regularly, her father K.V. Krishnamurthy Iyer having been a disciple of G.N. Balasubramaniam. She took up the tambura since she enjoys Carnatic music. She looks to identify new ragams and listen to different colours of familiar ones while on stage.

Tambura artistes incur tangible transportation expenses – Lakshminarayanan, Vaidhyanathan and Latha use auto rickshaws while Kalyani self-drives a car to concerts. They usually arrive at least 30 minutes prior to a concert and are in perfect readiness when the musicians arrive. For their 3-4 hours of time commitment, tambura artistes are paid Rs. 500 to Rs. 1,000 (affirmed by sabhas, musicians, All India Radio and tambura artistes themselves), an improvement from the Rs. 250-500 prevalent a decade ago. It is insufficient as a sole source of income and even this remuneration is at times forgotten and often not promptly remitted. Some tambura players have supplemented their earnings through other professions, others are receiving grants from governmental agencies and NGOs, while some see it as a passionate hobby. The driving force for all these tambura artistes, thus, is only a love for the artform – the desire to hear live music at close quarters while lending a hand.

R.K. Shriramkumar is so passionate about the tambura that he is asked to tune it at most of the concerts he is a part of. He strongly believes, as does vocalist N. Vijay Siva, that the voice takes on the character of the instrument used for sruti. “Everybody should sing to a tambura. Thyagaraja himself has extolled the instrument in multiple compositions,” Shriramkumar says, even as he laments the fact that I refer to the instrument as an acoustic tambura, to distinguish it from its electronic cousins. “That you have to do so is a tragedy that musicians have brought upon themselves by settling for electronic versions. Just as instrumentalists are expected to bring their own instruments to concerts, vocalists must be instructed to bring tamburas. Students of music should be encouraged to play the tambura for their gurus on stage to get a first-hand view of the constant give and take that can be experienced only from that vantage point.”

He commends The Music Academy for insisting on the instrument for the recordings of senior concerts for their virtual programs and hopes they will do so for other slots too. “Any music organisation worth its salt ought to have at least two functional tamburas in its arsenal – one each for typical male and female srutis,” says Shriramkumar. He mentions the Sruti Music and Dance Society of Philadelphia as an organisation abroad that has acquired tamburas and the Cleveland Aradhana which was given multiple tamburas by Shankar Ramachandran, the grandson of Kalki Krishnamurthy. Locally, Jayalakshmi Balakrishnan says Raga Sudha Hall has a dozen tamburas on site in various srutis.

Electronic devices, Shriramkumar suggests, can be used as a baseline to aid in the tuning of the acoustic instrument, but should not be kept so loud as to mask it. He is categorical, and Nisha and Vignesh concur, that the traditional tambura is irreplaceable in its depth and feel of sound and is definitely not for optics alone.

As more musicians show a renewed devotion to the instrument, it is indeed a paradox of sorts that the tambura is experiencing a resurgence even as its dedicated strummer is fading away. With negligible monetary or other benefits and so much music over the internet that is easier than ever to experience, the potential future tambura player (usually an avid rasika), has little incentive to take up the instrument. Students, more of them and ever younger ones, are taking on that mantle. Electronic alternatives are getting better by the day too with the added convenience of lightness and portability even as airlines get ever more restrictive with baggage allowances. The day without ‘professional’ tambura players might be much sooner than we think.

A much needed article on the importance of the traditional tanpura. Born and brought up in a family of musicians, as a child, I would wake up with the tanpura and even slip into slumber at night very peacefully with the soothing strumming of it. Much later, early in the morning, I would spend at least 15 minutes strumming my mother’s tanpura, soaking myself with the nadam that would resonate and fill me with an indescribable peace. My mother Smt. Leela Gopalan, the eldest daughter of Allapuzha K.Parthsasarathy Iyengar (Papasami), following the Ariyakudi bani was an AIR artiste in Lucknow radio. My daughter Vaishnavi is married to Bombay Anand. I am a disciple of Guru Dr. Padma Subrahmanyam. Hope and pray the live tanpura accompaniment will be back soon.

Thank you for reading and sharing your thoughts, Ma’am. Your reminiscences add picture and colour to a different milieu.

good piece. you gave life to the thampura players who were counted no more than set property.

Thank you for reading and commenting.

Great article! It brings back memories of Shri Tathachari, an indispensable member of the ensemble for Hinsustani concerts in Madras ftom the 70s to the 90s.

Thank you for reading. I am not familiar with the gentleman. Could you please shed some more light? Did he play the tambura?

Article much needed..i think in Andhra , we still see Tambura shruti being used in concerts ..

Thank you for reading. The tambura is used very regularly in Chennai as well – dedicated tambura players are becoming harder to find.

An Era where electronic substitutes are used (and preferred) in lieu of the actual Tanpuras for several reasons, the obstinacy to use Tanpuras even for practice shows the resolve of the musician and his/her dedication to not only the technicalities but also the aesthetics. This article delves a little deeper into this scenario and stresses the importance of not only Tanpuras but their players as well. Very concise yet quite detailed. Thank you very much for this.🙏🙏

Thank you for reading and for taking the time to comment.