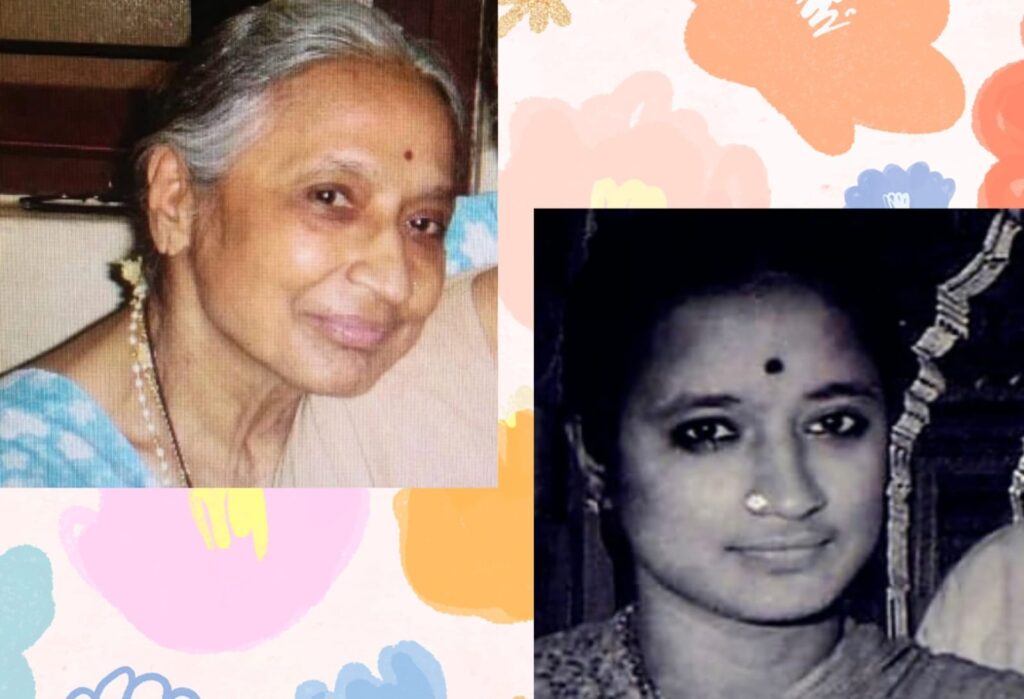

E. Gayathri

Gayathri Vasantha Shobha was born on November 9th 1959 in Madras. Her earliest musical memories are of her mother teaching veena at home. “I had no dolls. The veena was my doll,” she says. As soon as her mother’s students left, Gayathri would ensconce herself by the instrument, holding it the way she had observed, and try playing it. She never played smaller sized instruments – it was always the full sized traditional veena. Gayathri does not recollect learning any conventional basic exercises either – rather, she played any music she heard. Noticing this, her father thought she ought to take proper training. Her mother, Kamala, a vainika herself and a student of Kalakshetra, taught her the workings of the instrument and many compositions.

Author’s Note: When I was a child, I was fascinated with child prodigies I had read and heard of, such as E. Gayathri. It was many years later, as an adult, that I finally could attend her concert live. She still exuded a very child-like vulnerability and a definite pathos that simultaneously intrigued me and made me relive my childhood impressions – even as her competence on the veena blew me away. This article, based on my conversation with Smt. Gayathri, a senior A Top vainika who capped her career as the first Vice Chancellor of the Tamil Nadu Music and Fine Arts University, sheds raw and honest light on what it really was, and is, to be her. The photographs, except where specifically indicated, were provided by Smt. Gayathri.

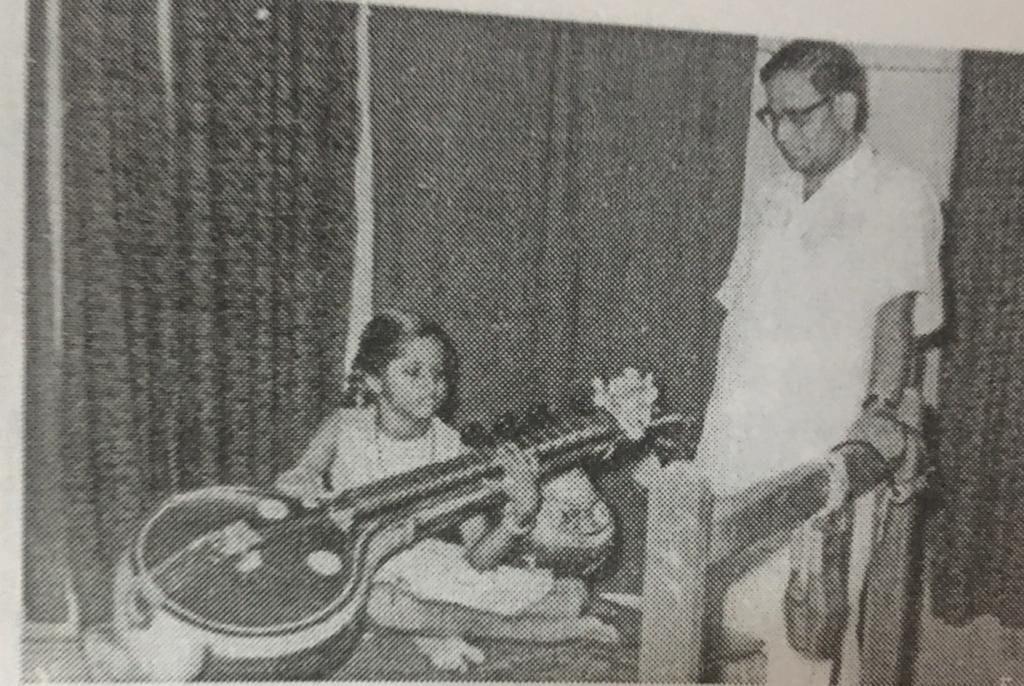

Gayathri’s father. G. Aswathama would wake her up at 3.30-4 am every day. Settling down with a cigarette, he would instruct his young daughter on the day’s practice. A native of Narsapur, West Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh, Aswathama was a film music director by profession but solidly trained in Carnatic music, having studied at the Vizianagaram Music College (along with P. Sushila and Ghantasala) and from Tiger Varadarachariar too. Gayathri recollects her sessions with her father very fondly. “First, he would make me play a rAgam – in the beginning, it would feel very strange – no ideas would come. He would tell me to keep trying – all this at about 6 years of age. My head would reach only the veena danDi,” she says with a smile. Aswathama would encourage her on daily manOdharma explorations, tAnam in jAla style, neraval and swaram, rAgamAlika tAnam and more. Aswathama listened to many types of music and Gayathri recollects his pointing out many aspects as he casually listened. She would immediately try to replicate it herself on the veena. She first performed for movies before entering the Carnatic scene, playing scores not just for her father but for other music directors as well.

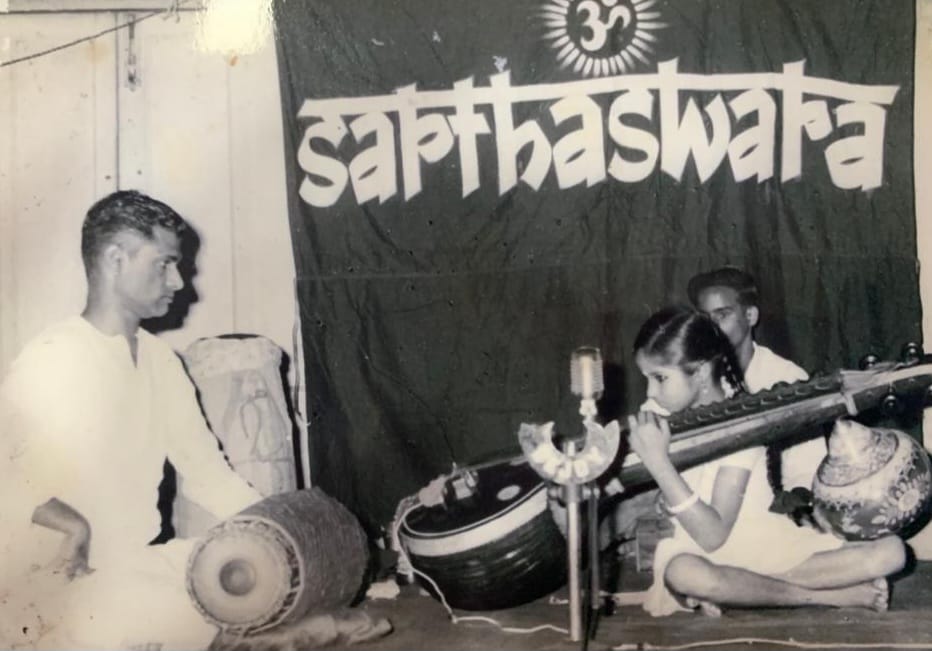

In 1967, when she was just 7, Aswathama organised a Carnatic chamber concert at their home to which he invited the media and many from the cine field like Chittoor Nagaiah and Lingamurthy and, notably, the renowned musicologist, Prof. P. Sambamoorthy. Speaking at the conclusion of this program, Prof. Sambamoorthy referred to Gayathri as a child prodigy. Thus hailed by the press as Sambamoorthy’s talented find, ‘Baby’ Gayathri became an instant rage.

Her first official Carnatic concert was at Parthasarathy Swami Sabha at the age of 8. The then president of the sabha, Venkatakrishnan, became Gayathri’s ex-officio manager for the next decade. All of her concerts had to be booked through him. Gayathri recollects his coming home regularly to discuss programs with her father. For several years, she had concerts practically daily, including several outside Chennai involving a lot of train travel. Did she ever protest at the punishing schedule? “Not when I was younger. In my teens, I sometimes felt it, especially on festival days when others were enjoying themselves. The pressure also increased; there would be times I would be tired. I was taking hostacycline before concerts to be able to sit through them.” For outstation concerts, someone from the family usually accompanied her, sometimes the entire extended family. Many of her concerts were 3 hours in duration with no violin. One of her earliest and most regular mridangists was Madurai T. Srinivasan and, later, T.H. Subhash Chandran (better known as a ghatam player).

Her father would draw up a list of pieces to play at each concert. “However, he would tell me that if midway I felt like playing something else, I should do so – he said artistry would flourish only with freedom, and I was not to feel shackled. He followed generally accepted guidelines for his selection of compositions. A subsequent rAgam had to provide a different colour from the previous one to grip the audience – so HindOLam should not be followed by a Suddha dhanyAsi – rather, a kalyANi and then a rItigowLai might be more appropriate. tALam variety was also to be incorporated. No more than twenty minutes were to be devoted to lighter concluding pieces. The main piece ought to be 40-45 minutes in length – without tani (if a three-hour concert) or with tani in a shorter one.”

Aswathama would attend her concerts and Gayathri would glance at him periodically from the stage. He would provide feedback then and there through hand signals. “He would ask me sometimes to take it more slowly and deliberately, for example,” she says. Post concert, her mother would not say much, Gayathri says, but her father would analyse each piece she had played and give detailed honest feedback but in a kindly manner.

He also maintained a diary where he noted down what she had played in each concert. Completely preventing repetition was often not possible, however, because of audience requests. “I was regularly asked to play himagiri tanaye (Suddha dhanyAsi), alai pAyudhE (kAnaDa), sAmaja vara gamana (hindOLam), raghuvamSa sudha (katanakutUhalam), chinnan chiru kiLiye (rAgamAlika), ninnu vina nA madi (navarasakanada), especially. Wherever I went I would get chits for these – I don’t know why they associated me with these songs,” she smiles recollecting. She continued playing movie scores as well at this time. “My mother would say I could use what I made in movies as my own pocket money,” Gayathri says. “I would use that to go with my friend Manju for a movie and buy something to eat or, sometimes, buy myself a dress.”

Did she have a special wardrobe for her concerts? “No wardrobe. I was actually playing in half skirts until elderly audience members told my parents to dress me in full skirts. I had four or five outfits I would cycle through. No silk. Just cotton and not even ironed. We could not afford anything more.” Here, she remarks that while one should be presentable, one need not obsess about wardrobe and accessories. “The music produced must be powerful enough as to envelope the listener so totally that they picturise only the music rather than the musician.”

Gayathri’s childhood familial unit consisted of her parents, her sister, her aunt Kumuda Aswathama (her father’s first wife and younger sister of Gayathri’s mother) and her half-brother. Her father had long suffered from a liver ailment and was thus never in the best of health. In 1974, Aswathama’s illness worsened after which she travelled only with her co-artistes. “My most frequent mridangists at this stage were Erode VR Lakshminarayanan and Kutralam Viswanatha Iyer. They took care of me very well and my father was comfortable with my travelling with them,” she says. Aswathama passed away in 1975 at the age of 48. All of 16 then, Gayathri was shattered. “I lost all motivation. I felt as though the ground under my feet had gone.” Even in the best of times, family dynamics had been prickly and financial circumstances always precarious. Now, she HAD to perform to keep the house running. Her mother also got a position in AIR’s Vadya Vrinda thanks to the largesse of some senior musicians who knew of their situation.

Given how many performances she gave then (several a week) and the family’s financial situation still not improving in any significant manner, does Gayathri feel, now on hindsight, that either she was underpaid or some of her earnings were siphoned away? “It is a natural question and I too have wondered. The fact is I do not know what actually transpired then – I was too young. But knowing what I do now of life, nothing would surprise me,” she says.

In terms of schooling, Gayathri studied until 5th grade in Vidya Mandir and then from 6th to 10th at St. John’s, Mandaveli. “I was missing so many days at school and found studies very daunting since I had no continuity. I had a concert almost every day.” She subsequently moved to Kesari High School in T. Nagar. “The management was very understanding – I went in only for exams, and some teachers even came home and taught me. I never went to college.”

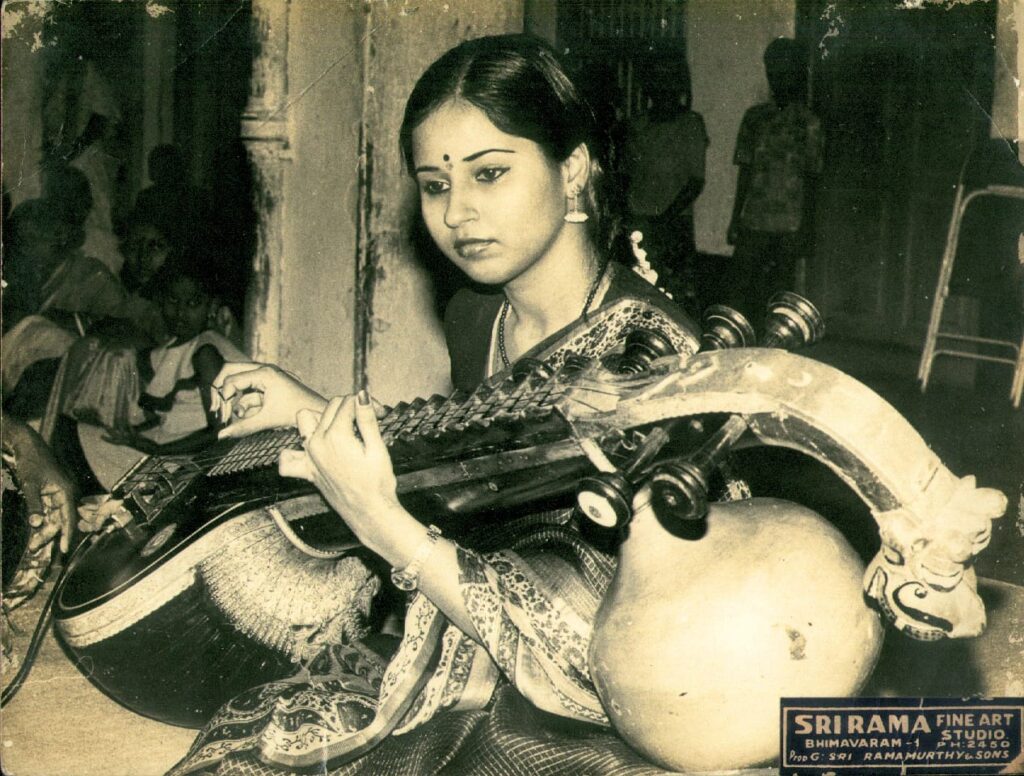

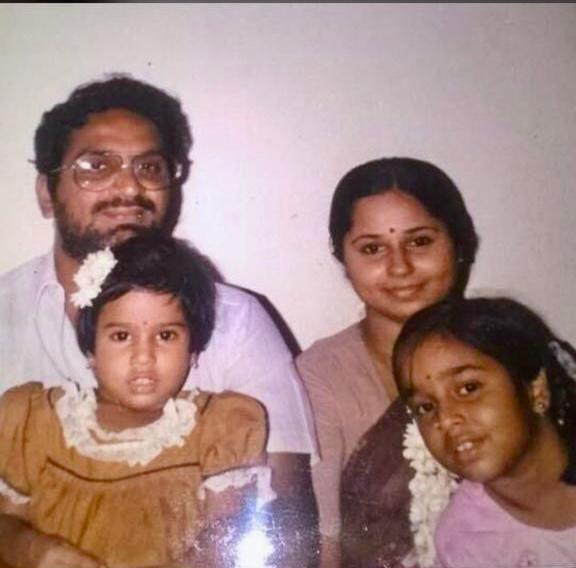

Her listlessness since Aswathama’s passing coupled with the complex family situation made her decide to get married. The then secretary of the sabha Kalasagaram in Hyderabad found her a match. E. Ramakrishna, 9 years older, hailed from Guntur and was a marine engineer in the Merchant Navy. “He seemed dependable. I was looking for someone who could take care of me. He came from a large family and they were all very nice to me.” They were married in 1979, and her financial difficulties now came to an end. After their wedding, Gayathri left with her husband on the ship he was working in, taking a hiatus from the veena. In 1980, she had their first child, Deeptha. The family returned to Chennai in 1981. Always very spiritually inclined with an interest in taking up sanyAsa, her husband was a rock of reliability and support and a source of great happiness in her life until his unexpected demise in 2021 of Covid.

Their second daughter, Haritha, was born in 1984. Gayathri credits her late aunt Kumuda for ministering to her children when she was away at performances at this stage of her life. While familially stable, artistically, she felt at a crossroads. She was performing but felt it to be mechanical and rather devoid of feeling. “I felt stuck and needed a kickstart for motivation. My manOdharmam was also suffering.” She expressed her thoughts to her good friend, mridangist Trichur Narendran. “He advised me to approach TM Thiagarajan (TMT). Learning from him was a fantastic and unforgettable experience.”

She set a veena to his sruti and left it in TMT’s home in T. Nagar. She would go for regular classes. “I would show up on time and he too would be ready with notations for that day’s piece that he would have beautifully written in Tamizh. Every class was thrilling.” He would sing the composition and Gayathri would play it on the veena. “He would make me repeat it a few times right there, finish each section, make it perfect and then go on to the next.” He would ask her to play manOdharmam aspects as well and make appropriate corrections. “After I played a phrase, he would ask me to start the next one from its ending note.” On the way back in the auto to her home in Besant Nagar, she would keep singing what had been taught that day. Gayathri’s spark to play was renewed and reinvigorated completely with TMT’s mentoring. He also visited Gayathri at her house periodically. “He enjoyed my food. He would sing a lot then and I would play alongside. I recorded many of those sessions. Unfortunately, they were all on cassettes which eventually got spoilt.”

Both her father and TMT played vital roles in her musical career, especially in approaches to manOdharmam. As to how they were different, she says, “Coming from a film background, my father straddled many genres of music, resulting a certain wildness in his imagination – he would stretch the boundaries. TMT Sir was systematic and strictly a Carnatic practitioner. Both were composers too – my father has composed bhajan-s, tillAnA-s and kriti-s in rAgam-s like sumanESaranjani, rEvati and more.

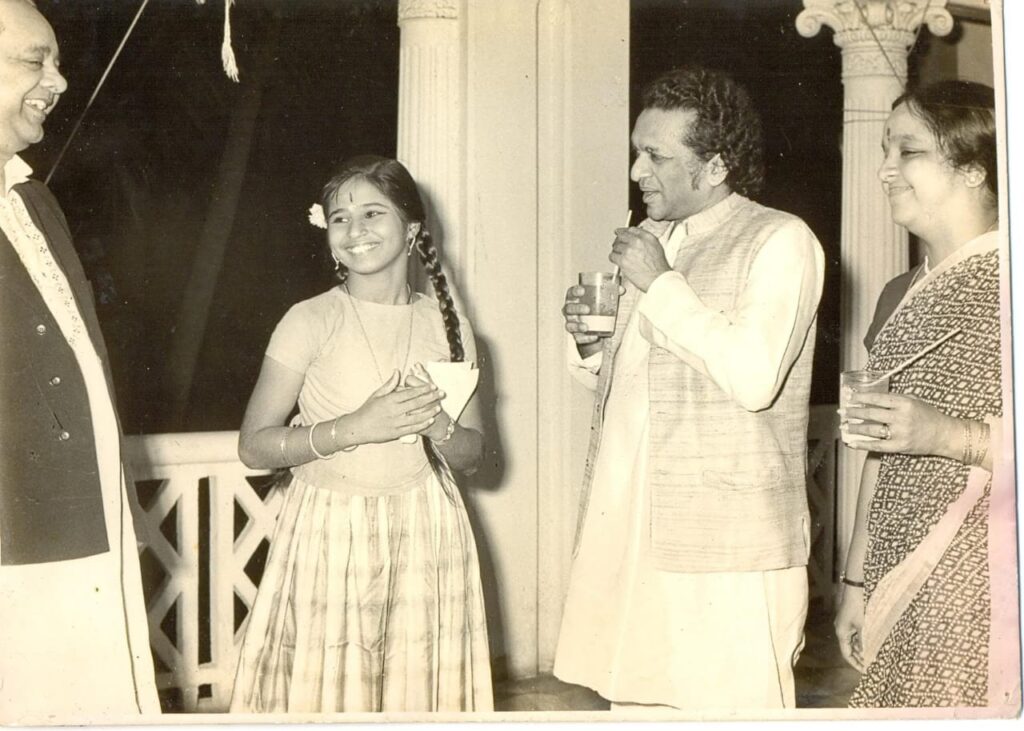

L-R: Sri. Allah Rakha, Smt. Gayathri, Sri. Ravi Shankar and Smt. Lakshmi Shankar.

Besides her parents and TMT, Gayathri also learned all the Navagraha kriti-s from MS Gopalakrishnan who also taught her some manOdharmam. “He would either sing or play on the violin and I would play it on the veena.”

She listened to various musicians like DK Pattammal, Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, Nedunuri Krishnamurthy, Voleti Venkateswarulu, DK Jayaraman and others, and took ideas from them. She was especially fond of DK Pattammal. “If I needed a reference, I would listen to her.” Gayathri admired Chitti Babu’s tonal quality a lot but was unable to actually learn from him. She got some guidance in earlier years from Kalpakam Swaminathan. “She is the epitome of veena for me. Because of her short stature, her spine would be erect as she played, allowing the kunDalini Sakti to flow freely from the base of the spine. There was strength and resonance in her playing which was weighty with clear gamakam-s. I learned some kIrtanai-s and tAnam from her. I played a concert with her in Stella Maris college when I was 7.5 to 8 years of age.” As a child, she says she focused purely on emulating the sound as she heard it – understanding lyrics and conveying bhAvam came later.

In 2001, Gayathri was appointed Member of the Iyal Isai Nataka Manram – for two years in a row. In 2011, the then Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa (JJ) appointed her Honorary Director of Tamil Nadu Government Music Colleges (Chennai, Thiruvaiyaru, Madurai and Coimbatore). Her mandate was to improve the syllabus and enhance the quality of education. As to how JJ knew about her, Gayathri recollects reading JJ’s interview in a Tamizh periodical where JJ mentioned Gayathri as one of the artistes whose music she enjoyed.

“When I was director of colleges, I took a proposal to the chief minister suggesting we create a University dedicated to the arts. She immediately accepted and announced it in the Assembly.” Gayathri was appointed the first Vice Chancellor of the Tamil Nadu Dr. J. Jayalalithaa Music and Fine Arts University – a specialised university under the Department of Art and Culture with the Chief Minister being Chancellor.

Gayathri dove right into efforts to both improve existing facilities and build new infrastructure. She renovated many colleges under the aegis of the university, built a new University block, had new cottages built for classrooms etc. “I arranged for a fleet of mini-buses for the convenience and conveyance of students and teachers who were called to perform at government functions. I requested and successfully got salaries increased for teachers appointed on a contract basis and raised student stipends as well. I set up a remuneration system to have external experts teach students periodically. I arranged for free bus passes for students. A students’ hostel was built at the Thiruvaiyaru college. The Chennai college hostel was completed. In the Chennai college, I got a wall erected near the river to prevent snake infestation. It ended up saving us during the cyclone.”

She faced numerous problems at the University, however, that caused her much distress. “There were several issues, union-related ones being especially rampant. Instead of focusing on curriculum and academics, daily life involved calling the police to handle miscreants. I received death threats. My office was invaded and posters pasted about me.” At her wit’s end, she spoke to JJ who provided her with a personal security detail and adviced her to be bold. With that backing, Gayathri took firm action which finally brought an end to the upheaval.

Her initial term was from 2013-2016. “In 2016, Madam CM gave the order for extending the term but was hospitalised soon after that. The bureaucrats were against me so that order was never issued.” The period was a highly stressful one, overall, she says, affecting her health negatively.

Gayathri has not been performing much in the past several years. She remarks that she does not believe that if one is a musician, one has to think about music throughout one’s life. “I am not able to think of music all the time. Maybe all the suffering in my life has killed the music in me or maybe I have outgrown music. A Sufi saint called Hazrat Inayat Khan who played the veena said he absorbed all that he could from the veena and then gave it up. I sometimes think I am headed in that direction. However, the nAdam of the veena energizes me – so I selfishly play a little to feel that energy. Physical impediments are issues as well. I have hip impingement and degeneration and cannot move with full ease. I abused my body too much in youth with excessive travel and performance, exacerbated by poor nutrition – we did not have today’s awareness then.” She adds that she has always played ‘true’ veena, playing every gamakam authentically, with bodily effort, never taking any short cuts even when she was very young with tiny fingers.

Cooking was a passion for her but lost its charm after her husband’s passing. Now pUja-s and exercise occupy her along with Facebook and her blog. “I post short clips of music since I receive many requests. I also post several observations on spirituality from my personal experiences.”

Gayathri is not a proponent of the many innovations appearing in the veena. “The veena should be made only from wood of the jackfruit tree – it is the wood grains that produce the nAdam – not the strings. Newer veenas use latest micing technologies where treble and bass can be adjusted and reverb given. But nAdam is not just volume – it is the aura around the sound. Only jack wood can produce that.” What does Gayathri think of today’s trend of many vainika-s singing along at their veena concerts? “I don’t think it is necessary. If one did choose to do so, one could do it for the pallavi line, perhaps. The veena can convey all aspects of the voice, and even more, by itself.”

She wishes there would be more veena concerts at sabha-s. “The number of sabha-s have increased manifold from when I first started playing. There are many excellent veena exponents now as well but the number of veena concerts are still very few.”

Asked if, on hindsight, she wishes she had had a normal childhood with a balance of everything, she recollects her school classmates’ parents recognising her as ‘Baby Gayathri’ and not enjoying the attention. “I did not realise the value of it then and would tell them that my name was Shobha. Outside of the concert stage, I just wanted to be a normal girl.” she says, with a smile. “I firmly believe in karma. Whether I like it or not, this is what God meant my life to be. If I had had a choice, yes, I would have preferred a balanced life mainly because it would have given me a feeling of normalcy. What I enjoyed most in life was playing with my classmates in school,” she concludes.

Related Links: