Dr. N. Rajam

For Dr. N. Rajam, who just added the Maharashtra government’s Pt. Bhimsen Joshi Lifetime Achievement Award to her already full kitty of honours (including the Padma Bhushan, the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship, and the Padma Sri), the many challenges she faced in the music world are no different from how one negotiates the difficulties of life. “For sure, it was not a bed of roses – there was opposition. But you deal with it rather than dwell on it,” the 82-year-old says, looking back on a lifetime with the violin.

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu newspaper. All the candid ‘in-performance’ photographs on this page are courtesy Sri. Ramanathan N. Iyer. Check out his extensive portfolio at Ram Iyer’s Imaginarium. My thanks to Ms. Nandini Shankar for sending the vintage and studio pictures here.

Until Rajam, the violin in Hindustani music was a non-entity with its few solo exponents unremarkable. Accompanying instruments were the sarangi, esraj, dilruba and the inadequate harmonium. Most instrumentalists then, Dr. Rajam says, followed the gatkari or tantrakari style – specific to instruments and distinct from the gayaki (vocal) style. “Right from the beginning, I wanted to follow the gayaki style on the violin for Hindustani music.” The magnitude of her pioneering efforts is compounded by the fact that she arrived as an anomalous South Indian (‘Madrasi’) female in the 1950s in a North Indian male-dominated art form.

Since the violin allows for continuity of notes, the gayaki style could be aped perfectly. “My style is 150% vocal,” she says. Never having heard an instrument sound that way though, her playing was a revelation. Many new things, however good they might be, are initially met with opposition and she did face skepticism. “At first, people were taken aback. Some said I was playing like Carnatic. But I knew I was on the right path and I persevered. Soon, everybody accepted. So much so that many aspire to play the way I do.”

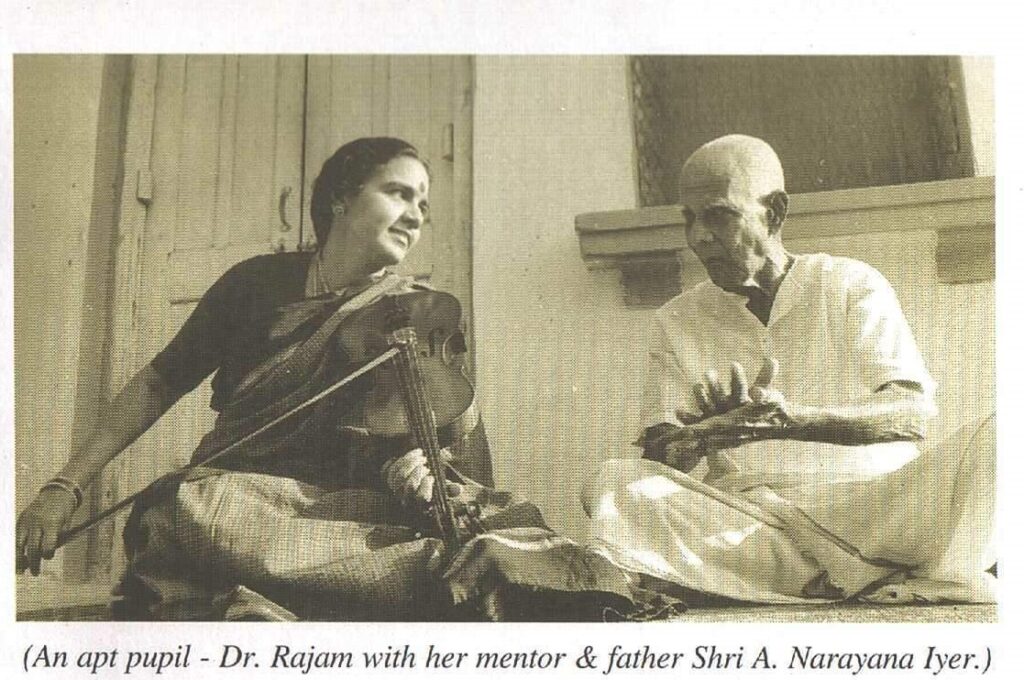

Dr. Rajam came to Hindustani music after 15 years of training in Carnatic violin. Her father, A. Narayana Iyer had taught her (and her brother, the celebrated Carnatic violinist T.N. Krishnan) the instrument rigorously. She had taken further stewardship from the titan Musiri Subramania Iyer as well and, at age 13, had accompanied M.S. Subbulakshmi. “I could play anything anyone could sing.” Her foray into Hindustani, interestingly, occurred because she was underage (14) to appear for the local ‘intermediate’ school leaving examinations (having received a double promotion early on). Learning that the Banaras Hindu University (BHU) had the option of appearing as a private candidate without the age requirement, her father registered her for it. One of the required papers was Hindustani music. To prepare for it, she took lessons from L.R. Kelkar, a Chennai-based Hindustani musician.

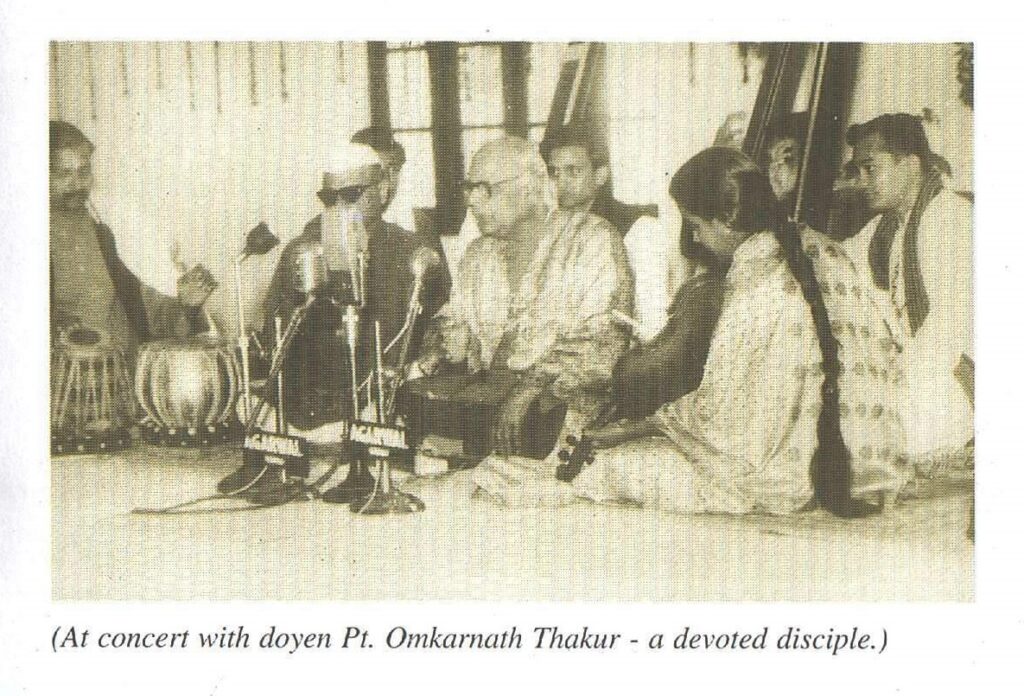

Simultaneously, a fellow Musiri student shared some 78 RPM records of Pt. Omkarnath Thakur. Dr. Rajam found his music captivating and decided that if she pursued Hindustani music, it would be under him. “When I went to BHU to write the intermediate exam, I took a letter to Omkarnath-ji, who was the Founder Principal of the Faculty of Performing Arts, from Parur Sundaram Iyer (father of violinist M.S. Gopalakrishnan) whom our family knew well. They were guru bhAi-s, both having learned from Vishnu Digambar Paluskar. Omkarnath-ji asked me to play – I reproduced what I had heard on those LP records. He was surprised to hear his style replicated so faithfully and agreed to take me on.”

Picture Courtesy: Sri. Ramanathan N. Iyer

On the difficulties in switching from Carnatic to Hindustani, where the tALam is not overt, she is candid. “Kelkar-ji, having lived in Madras, would put tAL by hand. I kept tAL with my foot, so while I did not err, I wondered how Hindustani musicians did it. The tabla player I practiced with would say, ‘kAli is coming’ (the start of the second half of the tAL, typically played distinctly), which I did not understand. I just needed to be told that it was based on the sound of the tabla – but since it was so obvious for them, they didn’t. I figured this out myself in 2-3 months.”

Kelkar was a student of Omkarnath Thakur’s disciple and thus, without even knowing it, she had been soaking in the Gwalior gharAna (style). The relevance of gharAna-s now is questionable, perhaps even out-of-date, with all styles just a click away. Dr. Rajam absorbs pointers from all gharAna-s, while staying authentic to the classical Hindustani idiom. “Between teachers preventing students from listening to others’ music and travel being cumbersome, styles stayed within narrow confines. While it is still possible to maintain the main characteristics of one’s originating gharAna, I am open to taking good aspects from others and have no objection to my students doing so either.”

Omkarnath Thakur was known to be rather difficult. Dr. Rajam, however, received only affection from him. “He said what he felt unfiltered, and rather crudely, which got him misunderstood. His standards were high and if he heard bad music, he would unhesitatingly call it out even on stage. Inside that rough exterior though, he was extremely good hearted. Since I played well, he never chided me.”

To facilitate her learning, the family moved to Bombay. She had her lessons when Omkarnath visited the city every couple of months for several days at a time. “My father accompanied me for class. Being from an orthodox family, I never went anywhere unescorted. I still don’t!”

Though Krishnan and she both learned from their father and the similarities in playing abound, there are clear distinctions as well, particularly in the left hand (non-bowing hand) technique. “Hindustani has some aspects not in Carnatic – like the vilambit (slow) and the ati vilambit (extra slow) tempos and the fast tAns (sequence of notes sung in akAram). My father helped me to work on these. These brought in some changes in my playing.” About learning from her brother, she explains. “Anna was 10 years older than me and left to do gurukulavAsam at Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer’s when he was about 12. So, as a child, I saw him only occasionally. Later, of course, we performed together on many occasions. He was very proud of me as I was of him.”

Dr. Rajam considers herself more a student than an artiste. In the past few years, she has been working on understanding what produces roughness (piSaru) in bowing. “We pay so much attention to our left hand – finger placement and the sound – and teachers are hypervigilant too. Similarly, I am focusing on how the entire bow comes into contact with the instrument and playing it very consciously. Codifying it comes next. Bowing technique is much more advanced in Western music where it has been extensively explored but in India, because of the integral gamakam-s which are difficult to reproduce, bowing technique has taken a back seat.” A feature of Narayana Iyer’s training was the use of the entire bow. “My father would insist on it. The bow had to be used fully even if it sounded imperfect initially. Sophistication comes later. Of course, I also know to use very small parts of the bow if needed!”

She spent nearly 40 years at the Faculty of Performing Arts at BHU, voluntarily retiring as Dean. On how she began, her experience, challenges and learning there, she says, “After I passed my BA in 1957 (incidentally, she topped the university jointly with the award winning astrophysicist Padma Vibhushan Dr. Jayant Narlikar), Omkarnath-ji asked me to apply for the position of lecturer there. For reasons including concern that a young woman might ‘corrupt’ the young men in the university, I got the position only two years later, in 1959. Learning about institutional politics was the biggest lesson – denying of students, delaying of promotions etc. – the usual. I followed my father’s advice of speaking minimally and only when necessary. A problem is immediately reduced in magnitude with silence. It might have been construed as arrogance but it was not arrogance. To the present day, I am measured in speech and will not cross the limit.” However, she says, she never hesitated to take any necessary actions as needed of the person of authority that she became. While at BHU, she also completed an MA in Sanskrit guided by Pt. Subramania Shastri and a PhD in Comparative Study of Hindustani and Carnatic Music under Dr. Premlatha Sharma.

Picture courtesy: Sri. Ramanathan N. Iyer

Her only child Dr. Sangeeta Shankar and Dr. Sangeeta’s daughters, Ragini and Nandini, continue her legacy. “Our family tradition is to hand a violin to every child, boy or girl, at age 3. That is what I did. We should teach our children what we know.” Whilst instructing, she is only a teacher and not an indulgent parent or grandparent, she adds.

As a performer, Dr. Rajam is known to be unassuming and easy to deal with. “I do not give organisers any trouble. I reach concerts well on time and will finish a minute before the requested concluding time. I have taught my daughter and granddaughters too to be similarly well behaved. One first has to be a good person. Only then is one an artiste,” she insists, devoid of any airs at all.

Related Articles:

So beautifully written about the living legend Smt Rajam. Thanks a pile!

Thank you.