A Tanpura Made in Pennsylvania

A scientific rethink of a craft steeped in tradition, when unencumbered by hallowed strictures, can shatter long-held beliefs, shed valuable insight and provide illuminating perspective. Dr. Bhushan M. Jayarao of The Pennsylvania State University, a non-musician, has constructed a tuneful tanpura in State College PA, USA, with local materials and knowhow from the Society of Indian Music and Arts (SIMA) – an organisation dedicated to preserving and propagating traditional Indian performing art forms. The construction of this tanpura breaks long-held, ‘sacrosanct’ beliefs on the making of Indian musical instruments – including particular geographical antecedents, very specific materials and inviolable modus operandi.

A version of this article appeared in The Hindu newspaper. All photos courtesy Dr. Bhushan M. Jayarao and Dr. Latha Bhushan – many thanks to them for obliging with answers to every question and supplying the step-by-step, chronological photographs. I am grateful to Sri. Arijit Mahalanabis and Sri. Kishan Patel for their efforts.

Arijit Mahalanabis, Founder of SIMA, reputed teacher and a recognised Hindustani vocalist adept in dhrupad, khayal, tumri and dhadra, says, “The construction of this tanpura was a first step in attempting to wean ourselves away from India for instruments. We find traditional Indian instrument makers having mental blocks in handling anything outside what they were used to – for example, male tanpuras outside the C# range.” Kishan Patel, director of SIMA’s Harrisburg chapter and a Hindustani vocalist, multi-instrumentalist and teacher, adds, “Another major issue is inconsistency – while brand-name musicians receive instruments of high quality, we find ourselves frequently shortchanged – particularly since we cannot test the instruments before purchase.” Arijit adds, “I also had a strong inkling that good instruments were not dependent as much on the specific materials that were usually insisted upon – sound is physics – construction, I thought, was more important.” Here, Arijit refers to the often very specific types of woods and materials insisted upon for instruments.

SIMA became acquainted with Edward Powell, a European luthier, who makes unique fused instruments including one which is a lute, guitar and sarod all in one. He has also created a sarod and a sursringar with the same techniques used to make an oud (a Middle Eastern lute). SIMA thus envisioned that a prototype of a tanpura was within the realms of local possibility.

Creating a complex musical instrument from a clean slate required a lot of thinking. Kishan explains some of the false starts. “We had a booklet that clearly explained how an oud was made – several strips of softened wood strips are glued together around a mould for the base. We tried soaking balsa wood strips (a soft wood used most frequently to make model aeroplanes) in a bathtub, but found that the strips, while flexible, were not strong enough to retain its shape around a mould.” Dr. Bhushan, on a drive to Washington DC, saw a farmer selling monster pumpkins (of the Halloween variety). He bought a few, hollowed out the insides and filled them with plaster of paris to obtain a mould for the thumba (or kudam) – the bulbous bottom part of the tambura. For the stem (dand or dandi), he inserted a PVC pipe. Once the pumpkin shell was removed, they had a mould. Dr. Bhushan’s idea was to drizzle and layer this shell with a mixture of sawdust and wood glue (several pounds of sawdust and gallons of glue were purchased) until the desired thickness was achieved to form the hollow thumba.” This was somewhat similar to the methodology behind fiberglass (different materials, of course) but given the amount of glue that it might require, the idea was soon shelved.

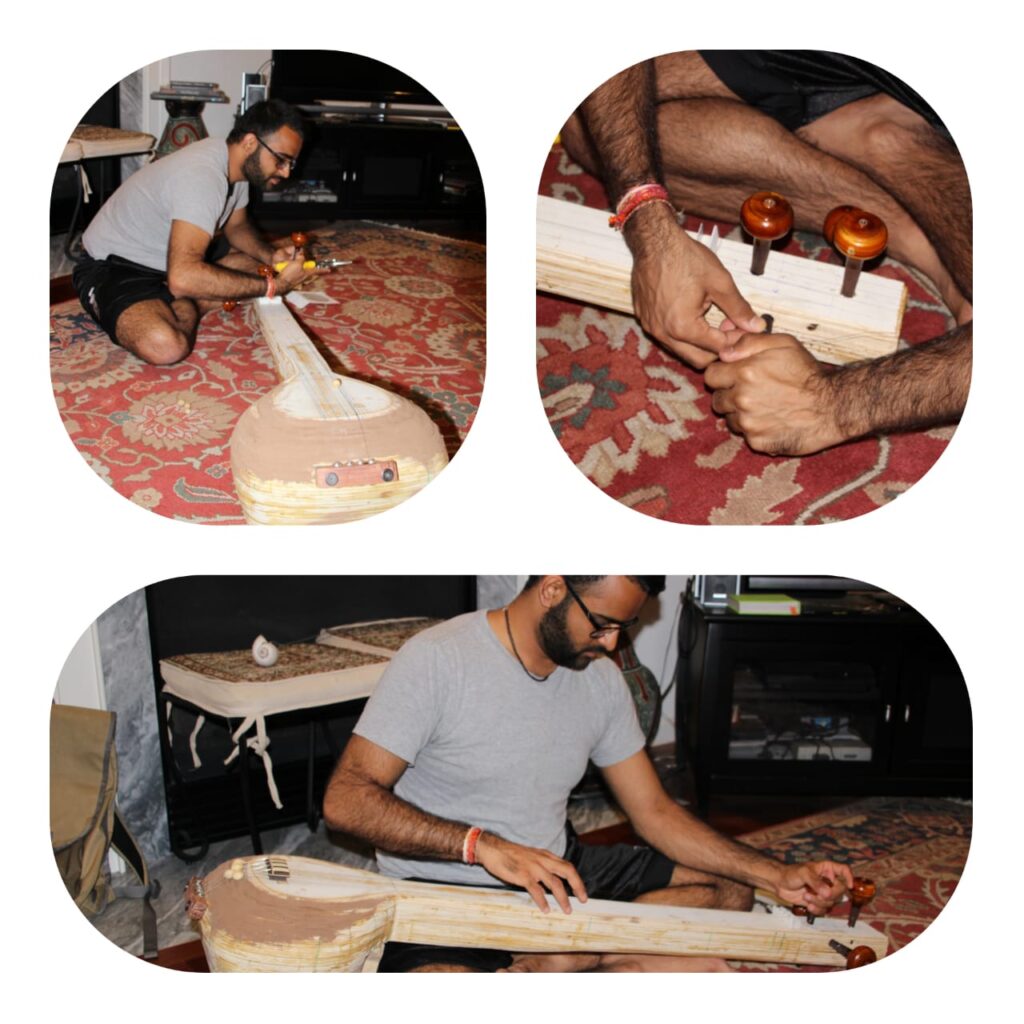

Dr. Bhushan, a Professor of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, regularly reviews histologic slides – images of thin cross sections of organic tissue. “So I felt constructing the tanpura as layers of sections composed into one whole entity was a feasible approach.” He used several 2’ x 2’ squares of 0.25” thick plywood, each individually cut and hollowed to shape, assembled and stacked to a height of 18” to shape the thumba. “Each section was cut using a rotary blade. They were then assembled with glue. The dand of the tanpura were also created the same way, with a hollow tunnel in it.” Where the kudam and the dand intersected, Dr. Bhushan traced it out in longer pieces of plywood and cut them out as contiguous pieces. In traditional Miraj tanpuras, on the other hand, the thumba which is a gourd, is connected the dandi, which is a separate piece, using a connecting neck piece. Decorations are used intelligently to mask the joints.

The face plate was then carved and fused together. Dr. Bhushan explains, “The structure required extensive hand and machine sanding using sanding surface grain size from 40 to 220. This was a delicate process; the inside was relatively easier, as the sanding was left to grain size of 120. We watched the exterior surface carefully to ensure its appeal to the eye and touch.” Kishan added the bridges, the tail piece, and the pegs. Dr. Bhushan’s wife, Dr. Latha Bhushan, a professor of Special Education at Lock Haven University, hand-applied three coats of polyurethane to seal. She subsequently used an oil-based paint, stripped and finished multiple times, for a final finish. She then did the artwork too by hand. While heavier than the female Miraj tanpura that was used as a model, Arijit says that sound wise, “the tanpura is soft and well rounded, not lacking in any overtones, but not as robust as a conventional tanpura.”

SIMA parallelly decided to order a tanpura for a male A# pitch through Edward Powell. Kishan explains, “Ed asked me for the dimensions of my best tanpura (diameter of the thumba, height and diameter of the dand, thickness of strings etc.) and what pitch it played at. He then came back with exact measurements on what a tanpura for A# had to be like. It turns out the dand for this one had to be a whole 7” longer – making the instrument practically 5’ 11” – as tall as me! He also gave us details on sound holes which some tanpuras have but not others. He explained how the size of the sound hole affects the pitch and that the thumba-s themselves have a pitch. If you hum that pitch into the thumba, you either get a standing wave or an oscillating wave – the type of wave depends on the size of the sound hole. One does not want a standing wave which makes the sound cut out.” SIMA was happy with the finished tanpura they received from Edward Powell.

Kishan received further insights into instruments while trying to replace the broken faceplate of his Santiniketan esraj which Indian experts said just could not be done. This did not dissuade him, however. To fix the esraj, the first attempt was a wooden faceplate which a student adept at woodworking made – but Kishan was not happy with the sound. “We realised then that the thickness of the faceplate makes a significant difference.” They kept lowering the thickness until Kishan achieved one that actually produced “such sweet sound – even better than the original goat skin faceplate.” However, that ideal thickness could not take the weight of the strings and the faceplate cracked. This, of course, affected the sound. Kishan then thought a support underneath the legs of the bridge might solve the problem. However, that secondary contact muted down the overall resonance of the instrument, much like if one were to put one’s palm face down on the resonating chamber of a stringed instrument. Arijit then suggested they try a synthetic head. Kishan contacted the Remo company asking them for a sheet for the synthetic material they used for kanjira-s (Remo manufactures a readily available synthetic kanjira). The company refused, citing patents. Then, Kishan bought a Remo Ambassador model drumhead instead. Kishan figured out what glue to use and how to stretch it tautly enough that it stayed at the same level of tautness. At around this time, the thumba of one of Kishan’s tanpuras broke (which they subsequently fixed by very carefully gluing all the broken pieces together). He thought he would use the bridge from the broken tanpura on the esraj’s new faceplate. Disassembling it, he realised that this particular bridge was two layers of deer horn with a hollow in between, standing on two legs – another two pieces. Until then they had assumed it was a single piece! The esraj, Arijit says, now has excellent sound, “perhaps even better than what it was originally.”

Cost of materials, mainly plywood and glue purchased at the local home-improvement store, was around US$250 (~Rs. 18,250). Dr. Bhushan estimates 400 hours of time from conceptualisation to finished tanpura. “This was a prototype – it should take much less time going forward. We now know what is crucial, what works and what does not,” says Arijit, who hopes to continue SIMA’s efforts in instrument making. Kishan adds, “We would like to hear from, and work with, those who could share further expertise.”

These endeavours provided Arijit another important insight. “I understood why many music teachers in India tell some aspirants that music is not for them. It is often just an issue of pitches not aligning. Teachers and instrument makers expect women and men to sing only in particular ranges of pitches. But that is a matter of physiology which, in the West, is recognised.”

He continues, “The prototype tanpura, our efforts with other instruments and what we learned from Edward Powell, have proven to us that Indian musical instruments CAN be made in alternate ways. This could help alleviate supply issues – for example, the larger gourds required for some tanpura pitches are unavailable in India and are sourced from Madagascar. Other instruments can also be reengineered. Almost all Indian drums are thought to be functional only if made from a single block of wood, but I have heard a tabla made from multiple pieces that sounded very good. Using multiple pieces makes it so much more environmentally sustainable too. Sound is just physics. Construction (the thickness of the wood, the depth of the hollow chambers etc.), rather than exact materials, affects sound and tonal quality more.”

Related Links:

Arijit Mahalanabis – Podcast, Arijit Mahalanabis – Live, Arijit Mahalanabis