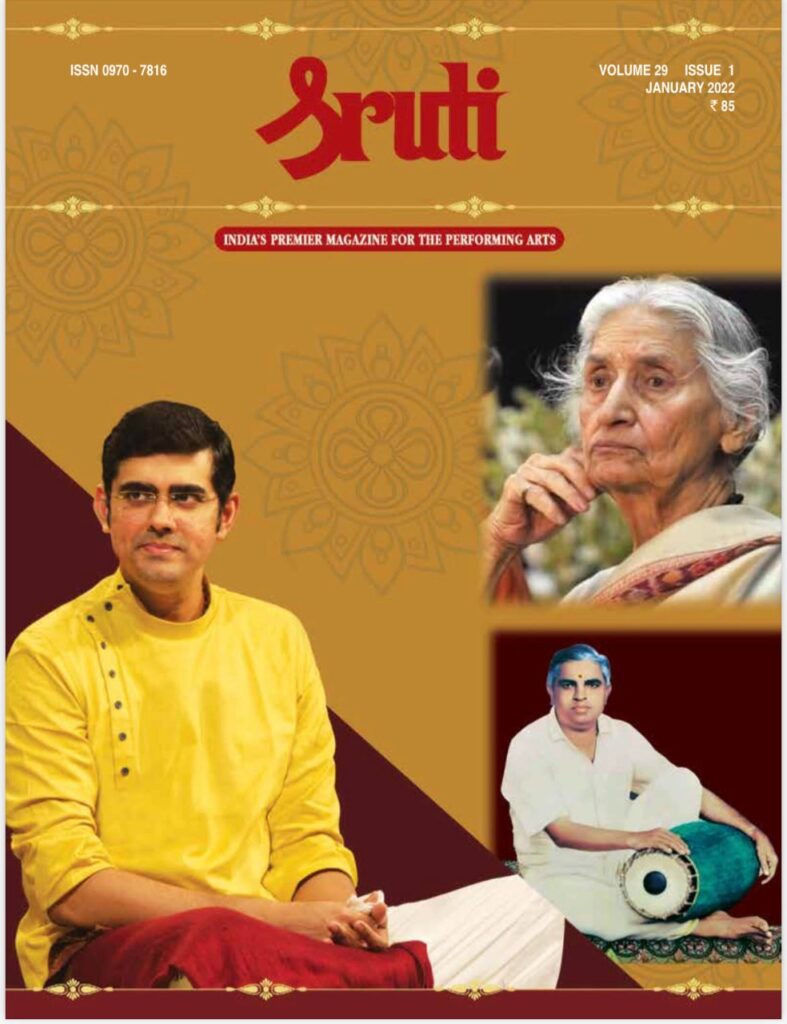

Sikkil Gurucharan

Sruti Magazine January 2022 Cover Story

(Note: The following is only an excerpt. To read the full article, subscribe to Sruti.)

How Sikkil C. Gurucharan became a vocalist is itself curious — even to him! Born in Chennai on 21 June 1982 to V. Chandrasekaran and Mythili (daughter of Sikkil Kunjumani, the elder of the Sikkil Sisters flautist-duo), he recollects his grandmothers testing the blowing ability of prospective flute students by asking them to blow into a pen cap. Gurucharan’s musical aptitude was discovered as a child when he whistled a film song correctly whilst walking down the stairs at his home. He then sang the same song, perfectly in sruti, which made his grandmothers decide that the boy should be trained in vocal music. Now, some 35 years later, he remains the sole vocalist in his family, almost everyone else having learnt the flute. “My mother had an arangetram in vocal,” clarifies Gurucharan. She, however, switched to the family instrument soon after and was on the flute faculty of the Tamil Nadu Government Music College for a few years. Gurucharan adds that his elder sister Lavanya, who too learned the flute, is most astute musically but elected to pursue academics.

Gurucharan’s mother, Mythili, began his formal training with small songs and slokas when he was six, in Hyderabad. The pieces were familiar to him, having heard them taught to young children by his grandmothers. Two years later, when they returned to Chennai, the boy got roped in by his grandmothers into their practice; he was asked to sing some sangatis, and the like, aloud. They firmly felt that he should get formal training from a guru outside the family. Vaigal S. Gnanaskandan, then with All India Radio, and a student of Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer and M.M. Dandapani Desigar, was chosen. Classes began in 1991 and continued actively until 2004-2005, with Gnanaskandan coming home to teach Gurucharan.

Gnanaskandan was a strict guru who did not cut Gurucharan any slack, something he is grateful for. “I had to keep the mat spread out, the water ready, and the sruti box on. I would even be seated and awaiting him. That was when he pulled me up and asked how I could be seated before he was. It was a good lesson imparted early.” The twice-weekly classes did not follow the conventional pattern. Gurucharan recalls singing sarali varisais in three speeds and being taught a few slokas. Very soon, he was taught Maha Ganapatim in Nata, followed interestingly enough by Vallabha nayakasya in Begada. Then it was a varnam. Nothing was written down, and neither were classes recorded. Gurucharan explains that it was not a fixed syllabus. “He would suddenly ask me to sing the alankarams and other basic exercises.” Not having learned these in the usual Ganamruta Bodhini chronology, Gurucharan looks at the geetams with fresh eyes and talks of singing the Malahari geetam, Sree Gananatha, recently in concert. “I had heard it, of course, when my mother taught it, but I had never learned it, and I wondered why it should not be presented in the concert circuit.”

Gnanaskandan believed in getting his students on to the stage within a few years of commencing tutelage. In 1994, he told Gurucharan’s family that he was to perform on a particular day for his Vaigal Gnanaskandan Trust, giving them four months notice. His grandmothers were a tad perturbed, not sure the boy was ready. In hindsight, Gurucharan thinks Gnanaskandan’s aim, more than announcing him as a performer, was mainly to reduce the student’s inhibitions in performing before an audience.

His aunt, flautist Sikkil Mala Chandrasekhar was a crucial keystone in Gurucharan’s early years as a performer, putting him through the paces firmly yet indulgently, expecting and pushing him to excel. Prior to his arangetram, she gave him written notes on how an alapana in Kalyani was to be structured, the phrases that should be present, and how it was to progress. Gurucharan views Mala’s mother-in-law, Radha Viswanathan – M.S. Subbulakshmi’s daughter — as one of his teachers too. Over their years of association, she affectionately taught him several bhajans and kritis that are a treasured part of his repertoire.

The list for that first programme was prepared by his grandmothers, based on the pieces he had been taught. The fact that Gnanaskandan did not object to this is something Gurucharan now marvels at, with his subsequent awareness of musician sensitivities. Once the list was prepared, it was Mala who made him practice diligently and conscientiously.

She also arranged for the co-artists for the concert – Neyveli Radhakrishnan (violin) and Poongulam Subramaniam (mridangam). While he had one rehearsal with them, it was Neyveli Venkatesh who had come in earlier, at Mala’s behest, for his first practice ever with the mridangam.

To read the rest of Sikkil Gurucharan’s story – Subscribe to Sruti – www.sruti.com

Related Links: