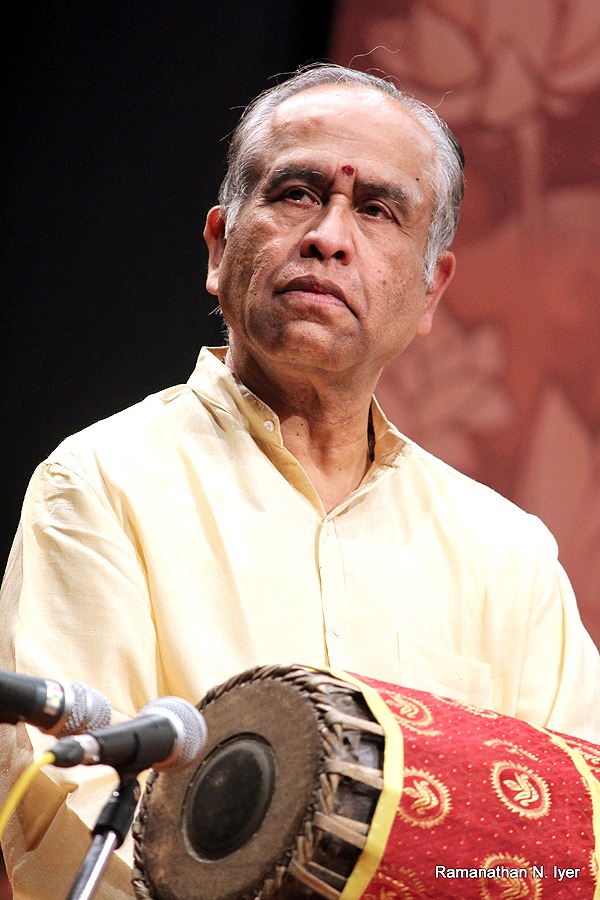

Trichy Sankaran

(Ram Iyer’s Imaginarium)

Known for nuanced and sensitive accompaniment, veteran mridangist and academic Sangita Kalanidhi Trichy Sankaran has played for Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer, Musiri Subramania Iyer, Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar, Ramnad Krishnan, Madurai Mani Iyer, G.N. Balasubramaniam, M.D. Ramanathan, K.V. Narayanaswamy, Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, Flute Mali and many others across generations. “I jokingly say that accompaniment requires an IAS,” he remarks, “where the letters stand for Involvement, Attitude & Aesthetics and Superior Patterns in Drumming.”

Sankaran, who turns 80 this coming year, began his training in Trichy with his cousin Poovalur Venkatarama Iyer, before joining the maestro, Pazhani Subramania Pillai. The best known of Pillai’s students, Sankaran has lived in Toronto since 1971 where he went at the behest of the late Jon Borthwick Higgins. Now retired as Professor at York University, he has been such a regular during the Chennai music season that many do not realise he is not local. He has several concerts this year, including at Sri Parthasarathy Swami Sabha, Mylapore Fine Arts, Carnatica, Thyaga Brahma Gana Sabha and more. Tomorrow, he performs at Chennai Fine Arts with V.V. Subrahmanyam and V.V.S Murari. On Sunday, he plays with Lalgudi G.J.R. Krishnan and Vijayalakshmi at Krishna Gana Sabha. “I have played for so many stalwarts at Krishna Gana Sabha,” he recalls fondly, “including at Lalgudi Jayaraman’s maiden violin duet concert with Srimathi Brahmanandam alongside my Guru. Krishnan and Viji are doing an excellent job of maintaining their illustrious father’s legacy.”

Much of Sankaran’s learning came on stage from playing double mridangam with Pillai for stalwarts galore (including Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar) beginning with his debut for the Alathur Brothers in 1955. “Watching my Guru adapt his playing for each artiste was fascinating – how he played for G.N. Balasubramaniam would be very different from how he would play for Madurai Mani Iyer, for example.” Pillai being left-handed and Sankaran being right-handed further aided learning by being able to watch fingering clearly.

This article appeared in The Hindu newspaper dated December 24, 2021.

On the mridangists of now, he says, “I would not want to over-generalise but they seem more sollu-ful (replete in rhythmic syllables) than soulful.” To acquire soulfulness, he recommends attending concerts in person and ‘creative listening’ – keen attention to why something is played, where and when. He suggests percussionists think of the ‘intent of the content’ rather than break everything down into numerical sequences. “The selection of germinal or foundational patterns for a song has to be done with due thought. For example, one cannot play for ‘ninnu vinAga mari dikkevarunnAru’ (PUrvikalyANi) which is in vilOma chaapu using standard misra chaapu sollu-s. We should pay attention to the gait of the piece, how the sangati-s are getting stacked and add just the perfect sollu-s to augment each sangati.”

Do current musicians think of his ability to elevate a concert and consult him? He says many of the artistes he plays with do. “However, I will not dictate because I am senior. If asked, I offer suggestions. Some artistes include songs I like or try out new kOrvai-s (ending sequences).” He adds a cautionary note on the trend to incorporate mridangam-based kOrvai-s in the music. “KOrvai-s made for music are set appropriately for the rAgam, the particular song and gait – key factors to be kept in mind – otherwise aesthetics will be lacking.”

Photo courtesy: The Hindu.

He gives an example of musicians and percussionists working in tandem. “Madurai Mani Iyer would dwell at the mEl Sadjam (upper Sa). My Guru would take up that mEl Sadjam in the chaapu of the mridangam knowing Mani Iyer would hold there. Only meettu sollu and chaapu will be heard. Mani Iyer would so enjoy it that he would leave some 4 Avartanams (tALam cycles) free for Sir to play.” Sankaran agrees that melodic artistes (vocalists, flautists and string instrumentalists) lingering on notes, and leaving gaps, allow percussionists to highlight better and think of what patterns to use subsequently. He refers to G.N. Balasubramaniam with Pillai, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar with Palghat Mani Iyer, K.V. Narayanaswamy with Palghat Raghu and Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer with him (Sankaran), as other classic combinations that demonstrated mutual understanding.

A vocal proponent of sarva laghu (spontaneous ‘timeflow’ patterns) over kaNakku (mathematically focused sequences), playing appropriately for the music is paramount for Sankaran. He explains that right from the beginning, he focused on the music as a whole, rather than percussive calculations. He adds that while one should know kaNakku, it should be used only when apt, and with discretion. He has waxed eloquent on playing entire concerts, including kOrvai-s and tani Avartanam-s, without any preset calculation, like the methodical, purposeful build-up of sangati-s in a song. Virtuosity should be demonstrated only in the tani Avartanam, he says, and strongly believes percussionists should learn some vocal music.

For the tani Avartanam itself, he recommends no more than ten minutes in a two-hour concert. “It would be good if all the percussionists on stage play with mutual understanding of proportion to the overall concert. Anything overdone is not enjoyable.”

On whether one can construct an impactful concert of a shorter duration, he says it is definitely possible with proper planning. “All India Radio pioneered it years ago with both 60 and 90-minute programs. Besides the obvious contrasting ragas, he stresses different kAlapramANam-s (speeds) over just tALam variety. “One can deliver an excellent concert with a few common tALam-s if the gait and songs are appropriately selected.”

Over the COVID hiatus, Sankaran worked on a composition titled ‘Chaapu Tala Maalika’ set to a 24 beat tALam counted as 3+5+7+9 (tiAram, kanDam, miSram and sankIRNam) and based on Kharaharapriya or Dorian mode. He presented it last month in Vancouver in a program titled A Life in Rhythm organised by his student Curtis Andrews. “We had guitar, vibraphone, mridangam, drum set and more and were also joined by a Carnatic violinist, Kaushik Sivaramakrishnan, from Edmonton. It was a very successful program.” He has also worked on some kOrvai-s and different approaches to naDai-s that he will be presenting at his upcoming concerts here. “My Guru said I should follow his path but create my own style. I believe I have successfully done that,” concludes Sankaran.

Related Links: