The Evolution of the Electronic Tanpura

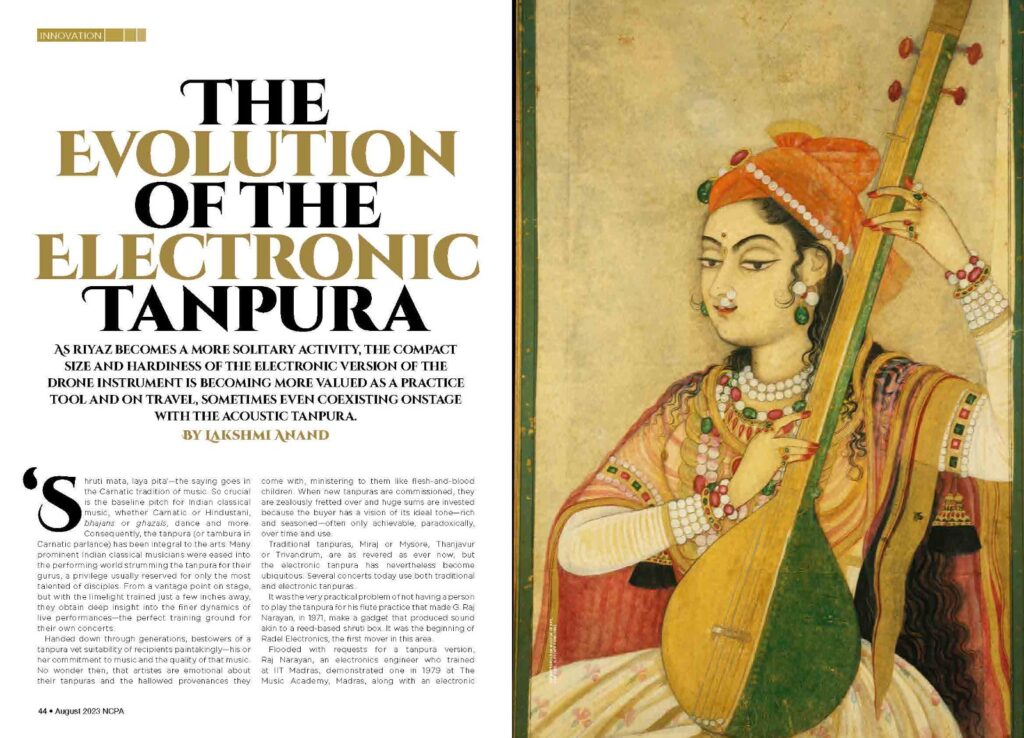

‘Shruti mata, layam pita’ – the saying goes in the Carnatic tradition of music. So crucial is the baseline pitch for Indian classical music – whether Carnatic or Hindustani, bhajans or ghazals, dance and more. Consequently, the tanpura (or tambura in Carnatic parlance) has been integral to the arts. Many prominent Indian classical musicians were eased into the performing world strumming the tanpura for their gurus, a privilege usually reserved for only the most talented of disciples. From a vantage point on stage, but with the limelight trained just a few inches away, they obtain deep insight into the finer dynamics of live performances – the perfect training ground for their own concerts.

This article is part of the Kalpalata Fellowship for Classical Music Writing 2023. It was published in the August 2023 issue of ON Stage, the official magazine of the National Council for the Performing Arts (NCPA).

Handed down through generations, bestowers of a tanpura vet suitability of recipients painstakingly – his or her commitment to music and the quality of that music. No wonder then, that artistes are emotional about their tanpuras and the hallowed provenances they come with, ministering to them like flesh and blood children. When new tanpuras are commissioned, they are zealously fretted over and huge sums are invested because the buyer has a vision of its ideal tone – rich and seasoned – often only achievable, paradoxically, over time and use.

Traditional tanpuras, Miraj or Mysore, Thanjavur or Trivandrum, are as revered as ever now, but the electronic tanpura has nevertheless become ubiquitous. Several concerts today use both traditional and electronic tanpuras.

It was the very practical problem of not having a person to play the tanpura for his flute practice that made G. Raj Narayan, in 1971, make a gadget that produced sound akin to a reed-based shruti box. It was the beginning of Radel Electronics, the first mover in this area.

Flooded with requests for a tanpura version, Raj Narayan, an electronics engineer who trained at IIT Madras, demonstrated one in 1979 at The Music Academy, Madras, along with an electronic talameter and the shruti box. So fascinated was M. Balamuralikrishna with the electronic tanpura that he requested one immediately for his personal use. The celebrated Carnatic musician used it at many concerts sans traditional tanpuras – a revolutionary act then, bordering on sacrilege . This was the hand-made Saarang, for long the only electronic tanpura in the market.

More progress was made through automated processes with compact, mouldable plastic cases and multiple variations. In 1999, the first sampled sound-based tanpura – which synthesised sound from a recorded real tanpura – was produced. Never patented, Radel’s ‘tanpura-in-a-box’ has many clones now, with Raagini Digital from Sound Labs being a popular competing product.

Parallelly, the gurukulam system had begun to erode away and music became a more solitary activity. By removing the necessity for a second human and pricing at a fraction of the real instrument, electronic tanpura manufacturers made practice on demand possible for everyone and eliminated major entry barriers for aspirants. As the music and musicians travelled globally, the compact size and hardiness of the electronic versions became increasingly more valued even as airline luggage limits tightened. It was a seminal chapter indeed.

The next big leap occurred when Android and iOS opened their platforms to developers in 2008. To have a tanpura on the smartphone one already carried was incredibly convenient. Created by a Hindustani musician and computer scientist, Prasad Upasani of California, iTanpura, released in 2009, was possibly the first ever paid tanpura app. Using sampled sound from his own Miraj tanpuras, it took off at once in the USA.

Among free apps, the Tanpura Droid is popular. Easy to use, it suffices for casual users and occasional singers.

Bheema Pro is a paid app created by Mukunda Haveri of Bengaluru, a Digital Signal Processing engineer, who converted a Windows-based application to this app in 2013. Combining his detailed study of tanpuras with samples of one string recorded from his Miraj tanpuras, he developed detailed analysis models to extrapolate the other strings.

While all the above versions of e-tanpuras use synthesised sound or sound extrapolated from samples of real tanpuras, the eSWAR app is different. All shrutis on it are real recordings of seasoned tanpuras belonging to veteran musicians, recorded from air-suspended mics, played by a professional and tuned to 440hz at a controlled 18-degree temperature. eSWAR offers Thanjavur and Miraj styles as separate paid apps.

The ideal tanpura strummer is expected to play the instrument with remarkable, non-trivial, monotony – consistent spacing between strings and even pressure on them. Purely a drone instrument, there is no improvisation either, making it ideal for automation. The corollary explains why the electronic tabla is still, for the most part, used only in practice. Traditional tanpuras are affected by changes in temperature, humidity and the very act of strumming itself, necessitating intermittent re-tuning amidst concerts. Additionally, the tanpura is usually strummed behind, or immediately adjacent to, the headliner artiste – making them inaudible to others on stage in today’s larger venues with more localised mics. The electronic tanpura is, thus, increasingly being used as a baseline to tune oneself and the instruments, including the traditional tanpura.

However, the creators of electronic avatars themselves only sought to mimic the instrument. The traditional tanpura cannot be perfectly replicated, they attest, with its multiple points of resonance, sheer size, the passive resonance of one string on others and the individuality in plucking that can change the tenor of the instrument itself. There is no substitute for the aura and ‘presence’ a traditional tanpura lends either. In a survey administered by this author to several performing Carnatic musicians, almost everyone indicated they preferred traditional tanpuras – though they appreciated the quick, readily tuned convenience of electronic tanpuras as a quick practice tool, for supplementary shruti and on travel. It appears that the traditional and the electronic will be co-existing for the foreseeable future.

Related Links:

Well covered article | thanks for sharing my thoughts

Thank you for taking the time, Sir. Much appreciated.

Brilliantly researched and written! I must congratulate the author Lakshmi Anand!

Thank you very much, Naresh-ji, for your kind comments and for all your assistance.